Earlier this year, the Pentagon announced it would be unveiling a new combat medal to honour, among others, the pilots in America’s increasingly unpiloted Air Force. The Distinguished Warfare Medal was supposed to acknowledge the changing face of American warfare—among those now eligible for medals would be drone pilots and computer security personnel. Almost as soon as it was announced, however, the proposed medal became a target of its own.

It didn’t help that the medal would have outranked the Purple Heart, a medal earned by those injured or killed in battle. It’s one thing to give a guy a medal for sitting in front of a computer on a Nevada base. It’s quite another for that medal to hold distinction over the one earned by a guy brought home in a box.

So the Distinguished Warfare Medal was cancelled two months after it was announced, and it’s not hard to understand why. But on a day set aside for contemplating the costs of war, it’s worth considering how the way we fight wars now changes our observance of those wars. If “going to war” no longer means leaving your loved ones at home, much less putting yourself in harm’s way, what are we remembering, anyway?

The burden of war is still horrific, both for the people asked to fight them and for the countries in which they’re fought. But the words “Modern Warfare,” even when they’re not being applied to videogames, have about as much resemblance to Saving Private Ryan as they do to the longbows and cavalry at Agincourt memorialized in Henry V. The Distinguished Warfare Medal shows that in a real way, we don’t even understand it as war anymore.

It’s possible this has less to do with the technology and more to do with the type of war we’ve fought so far in the early 21st century. That drones are being used primarily against people who can’t reasonably shoot back is an inextricable part of the moral queasiness we feel about them. At least one analysis has found that drone strikes are actually morelikely to create civilian deaths, despite the claims to precision from their boosters. Maybe we’d be more charitable to the contributions of our drone jockeys if they were doing something more obviously useful than blowing up tents and military-age males.

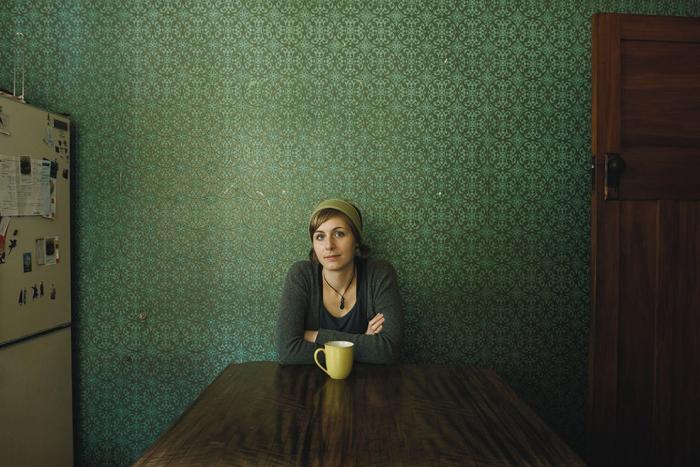

Of course, for the vast majority of people, this discussion will be meaningless: the other reality of modern warfare is that it’s almost entirely invisible except to those fighting it or their families. For Canadians at home, the most visible aspect of the war in Afghanistan was the occasional police-escorted hearse arriving at the coroner’s offices in downtown Toronto with a soldier’s body.

Remembrance Day is supposed to be a time to focus on the costs of war, and, in remembering, hope to avoid such calamities in the future. That may have been easier in a time when war meant mobilizing armies of millions—it was impossible not to understand the costs of battle when every family could name someone who was missing every Christmas. The fear for the 21st century is that policy and technology are conspiring to rehabilitate the pre-WWI idea of small wars that the electorate barely notices, much less cares about.

That era came to an end for a reason. And we remember November 11 for the same reason: we can’t trust our leaders, on their own, not to start a bloodbath in our names.