It’s no secret that Canada has long been seen as a land of two solitudes. The border, infamously articulated in 1945 by novelist Hugh MacLennan, between the country’s English- and French-speaking populations crosses through culture, religion, food, law, politics, and, of course, graphic design.

Okay, that last one might be a little bit less self-evident. But it’s no less real, particularly when it comes to book covers. In beautiful, bilingual Montreal, bookstores typically lean one way or the other linguistically but still feature a section devoted to literature in the city’s other main language, so that customers might see how the other half reads. Walk into any of these and spend a few seconds staring back and forth at the book covers in French and the ones in English, and the divide will jump out at you.

It’s like black and blanc, or nuit and day. You get the picture. It’s a contrast. While it might not necessarily be something that everyone has the words to describe, the sense that the two cultures make use of their own separate visual languages quickly becomes evident.

If you know a thing or two about graphic design, you might be able to sketch what it is that constitutes that difference you’re seeing. For starters, take colour. The anglophone books, you’ll see, use just about every colour in the rainbow. For the francophone ones—well, let’s say that white, off-white, and cream represent an outsized portion of the whole.

Then, we have fonts: where English cover text again runs the gamut, with words both overlarge and too small, both serifed and sans (and some probably trying to bridge the gap), and occasionally bursting into scripts a-swooping, in French the words manage to be set both less and more extravagantly, with neither the minimalism of the minimalist English-language covers nor the bombast of the maximalist ones. In short, they occupy a sort of comfortable middle position.

Speaking of middle position, when it comes to layout, French books tend to see centred titles, with the author’s name packed in close to the book’s, as if afraid to stray out on its own, both printed in the same tidy, Times New Romanesque font as often as not. Anglophone books, meanwhile, obey no such visual rules. You’ll find author name and book title not especially tethered together in size, shape, colour, or location, and subtitles now take up healthy chunks of real estate on nearly every non-fiction title released, whereas they’re all but absent in French.

Of course, not every book tracks neatly along these lines. There are French-language books that jump off the shelves and English books too shy to call attention to themselves. But it’s hard not to come away from studying the juxtaposition with a clear sense that the two solitudes are, if you will, speaking different languages.

***

Where does that difference come from? As a lifelong Montrealer, book nerd and “graphic design is my passion” utterer, I wondered about this for years. Unsurprisingly, as do so many questions of Québecois identity, the genesis of the story begins back in France.

I happened upon it in a quite accidental way—though, in retrospect, perhaps an obvious one. I was reading through The Look of the Book: Jackets, Covers, and Art at the Edges of Literature, a collaboration between writer David J. Alworth and designer Peter Mendelsund in the form of a fat coffee table book I’d received for Christmas in 2020.

On page 98, past reproductions of 30 different versions of Lolita, a quick sketch of the history of print, and an anecdote about a book literally bound in human flesh, I came across this half-sentence keyhole into the issue: “In France the look of the book was standardized—yellow paper jackets with black letterpress type prevailed…”

Of course, I thought. The difference was far too pronounced to be exclusively cultural in nature. There had to be something firmer—a foundation—underlying it. A foundation of law, not unwritten, but legally binding. (Book pun.) But now I had to peer into the dusty shelves of the matter and find the history section. Where might someone find such a law? I pondered about where and how to dig into the history of French publishing. But first, I wanted to look a bit more into the state of contemporary Québecois cover design.

***

As someone who translated a Québecois bestseller into English in 2021, these questions aren’t merely academic to me. In the lead-up to the publication of Made-Up: A True Story of Beauty Culture Under Late Capitalism by Coach House Books in the fall of 2021, I discussed the visual translation work necessary to transform the original Québecois cover of Maquillée to something more enticing for anglophone audiences with the book’s author, Daphné B., and my publisher, Alana Wilcox. Instead of the soft-hued foggy quality of the original, I craved something a bit more, for lack of a better term, obvious.

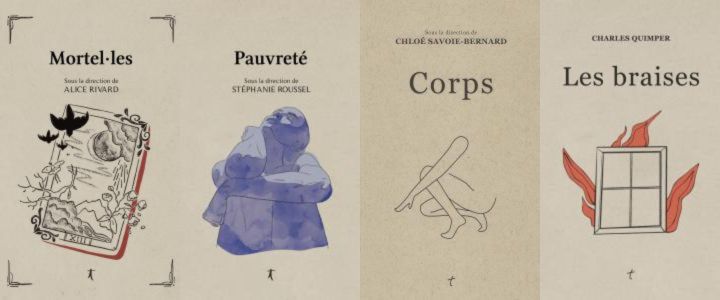

It was only natural, then, that I would ask Daphné herself about Québecois book design. She painted something of a glum picture. Québecois publishers like Le Quartanier use a single colour for their covers, she said; Éditions Triptyque uses stock photographs. In part it’s a question of sheer manpower—Les éditions de ta Mère uses a single cover designer, Ben Tardif; at L’Oie de Cravan, the publisher himself, Benoit Chaput, does double duty as the cover designer.

Marie-Julie Flagothier, an editor at Nota Bene, also plays a role in the design process there, and spoke to me about what it’s like. If you’ve noticed Québecois books’ design principles, well, yes, she admitted, some of the minimalism may stem from a minimalism of budget.

“With a template like the one we use, even if the work on the cover is different from one book to another, we don’t need to reinvent the whole look each time: we’re using a specific formula, which helps save us some time—in theory, at least,” Flagothier said.

The eye-catching English-language books you see in bookstores, their covers artfully designed, typically come from design teams either in Canada or the US. Books will sometimes have separate covers done for their Canadian and American releases; others will have just a Canadian one or just an American one, depending on where the publisher is located and their budget.

Still, as Flagothier noted, on the English side of things, “each book typically has its own unique visual identity that’s not tied to those of other books published by the same publisher, or even within the same collection.”

While this means that each book gets a design that fits its own feel best, it does strip it of the context that comes with the Francophone model, where uniformity of style helps render specific publishers’ work distinguishable: “at a glance,” Flagothier pointed out, “you can tell that a book is published by a particular publishing house, which I think booksellers and readers appreciate.”

Regardless, compared to the French-language Québecois publishers, English-speaking publishing houses in North America typically have significantly more—and better-paid—cover designers in their employ.

In fact, at bigger publishers, the job of a book’s visual design might be broken down further, with a whole other employee tasked with designing the inside of the book, from the look of chapter pages to the interstitial marks separating sections to the patterns on the inside of the covers.

Behind the scenes, designers, as Mendelsund himself explored in his aptly titled 2014 book Cover, work untold hours on mockups that will never see the light of day as designers, editors, marketers, publishers, and sales directors venture down different visual pathways before settling on one they like—a luxury that Québecois publishers simply do not have.

***

As it turns out, I was wrong about the French law that started all of this. It wasn’t a legal matter; the “standardized” look Mendelsund spoke of wasn’t a question of legislation at all. It was a conscious, powerful reaction to a previous, alternate mode of book cover design, a truth I discovered in a multi-part history of book cover design from the French perspective on Grapheine.com.

The French tradition of austere book covers began in the 1910s. That’s when André Gide, in charge of a major French publishing house called NRF, which would become Éditions Gallimard at the end of that decade, decided it was time to clean up the look of the book with majority white—or, really, cream—covers.

It was an attempt to push back against a prior mode of cover design. In order to signal to the reader that the book contained something of intellectual and artistic merit, to clearly and unapologetically differentiate it from the pulpy, ‘trashy’ novels of the day which had exploded in popularity as literacy rates increased through the nineteenth century, the cover had to be as simple and spartan as possible.

It almost feels like an example of the anthropological concept of “schismogenesis,” which I first encountered in the delightfully minimalist-covered The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow: the creation of an identity as a deliberate rejection of another one, verging on a kind of cultural-production NIMBYism. No scandalous maidens being ravished by rogues here—we’re talking about ideas, please.

The move worked, clearly. Though it’s gone through subtle shifts and seen all kinds of tweaks and takes on the basic minimalist principle he championed, decades and decades later, French-language literature was still very much in the thrall of Gide’s mode. Some Québecois publishers hew closely to it to this day: take a look at Groupe Nota Bene’s “Encrages” series, for instance.

There’s a certain logic there. A pure cream cover may not scream “excitement,” but they are harder to screw up. With tight design budgets, would you rather an austere look or an uncomfortably in-between vibe, like early twenty-first-century French design that mixes colour blocking and stock photography (say, this edition of Marc Levy’s Et si c’était vrai…) and some of the least interesting font choices you’ve ever seen (say, this edition of Virginie Grimaldi’s Le premier jour du reste de ma vie…)?

Either way, over the course of the past one hundred years, the trend never seemed to meaningfully bleed over into English-language publishing. But it’s not especially surprising that American culture didn’t experience a similar backlash to the design trends of its own pulpy, trashy paperback novels.

France’s longstanding cultural-intellectual tradition doesn’t really have an equivalent in the anti-intellectual atmosphere of American culture; second, the primacy of American capitalism undergirds everything in the country so thoroughly that any one editor attempting to push back on a given visual trend would last about as long as it took for sales to plummet.

And, in any case, the presence of a greater number of publishers in America, as compared to France, made it harder for a kind of cabal-like design approach to take over the market. At the core of the anglophone book design ethos is the reality: whatever sells, sells.

***

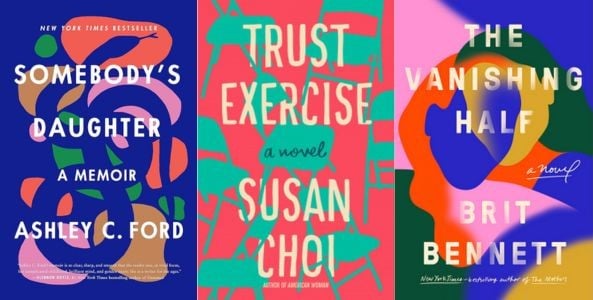

The fun part of all this is that English covers have been, in their own way, tilting back towards an arguably more francophone aesthetic in recent years—one marked by more dominant text, with a decreased focus on images, often eschewing photographs or concrete visual representations entirely.

Though it’s not quite the austere minimalism of last century’s Éditions Gallimard books, the contemporary trend, described as “blobs” in The Week and in Print Mag, is likely, in part, a reaction to the fact that contemporary books sell first and foremost online, and thus the covers are necessarily being seen at a fraction of their real size. Unable to communicate clever visual ideas or narrative moments at a life-size scale, the title and author’s name become all-important; they’re set against colour blobs to give the book just enough pizzazz to stand out.

Of course, the covers of these books aren’t pure colour blobs—they’ve almost got a Magic Eye quality to them. Study them up close and details will emerge.

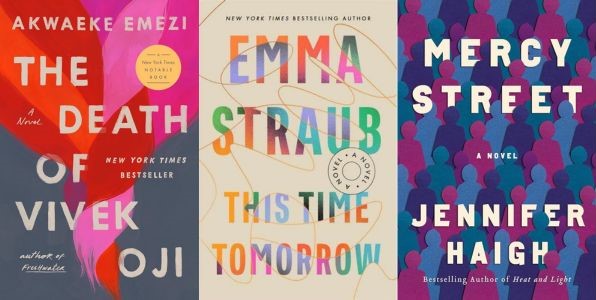

You’ll find faces staring out at you from titles like Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half and Torrey Peters’ Detransition, Baby. The cover of Trust Exercise by Susan Choi resolves into a cacophony of metal folding chairs, while Jennifer Haigh’s Mercy Street grows into a menacing crowd; a snake slithers through the cover of Ashley C. Ford’s Somebody’s Daughter, while a plait of braided hair does the same for Akwaeke Emezi’s The Death of Vivek Oji.

Not content with the status quo, This Time Tomorrow by Emma Straub cleverly inverts the principle, turning its text into the colour blobs themselves, and leaving the background a specific, practically Gallic eggshell colour.

Still, the trend did produce a backlash of sorts on social media, that suggests we may be ripe for yet another shift before long. The success of viral posts like this TikTok by @rileyhotsauce and this Instagram post by @reductress show that perceptive readers are onto the trend—and they’re not exactly thrilled by it.

Will book covers like those in Anteism’s distinctly Gide-an series or the one for Disorder, a poetry collection publishing this spring by Concetta Principe, prove a good way for Anglo publishers on a budget to make a name for themselves by zigging when the rest of the market zags?

Meanwhile, in recent years, French designers have been slowly breaking with tradition. Flagothier noted that she sees more and more books in French embracing the typographical ‘playfulness’ of English language design as of late, while others have found ways to dazzle while staying true to their minimalist roots.

Editions Folio, for instance, recently re-released four titles by female authors—Annie Ernaux, Simone de Beauvoir, Maryse Condé, and Marie NDiaye—whose covers featured simple black line drawings of their authors. What made them stand out was what they were printed on: a shimmering, mirror-like material that lit each cover up with a rainbow glow when it was angled in the right direction.

It’s the Magic Eye trick again. As ever, whether a book’s cover is enticing or humdrum depends on where you’re looking at it from, whether from one side or the other of a cultural divide or simply from which spot in the bookstore.