When I was twenty-one I believed cameras were for tourists, so I drew a picture of the Taj Mahal in ballpoint pen instead. In my drawing, the Taj looks like a melting ice cream sundae topped with birthday candles. In the foreground, there’s a misshapen rectangle that’s meant to be an ornamental pond, and behind it are four shrubs, or maybe four dwarves. It looks, as I described it on the facing page of my journal, “like a sugar-candy palace, like a white-icing wedding cake model. Like a spaceship landed in a totally inappropriate part of the Earth.”

I had been wandering around India for four months, trying earnestly to observe without objectifying. I had originally come planning to work on a commune where I would learn how to distill medicine from traditional herbs and build a mud hut to live in while dressing all in white; the commune turned out to be just a guy with a big backyard, so I left. “A young girl dressed in flowing white rides past on the back of a motorcycle, trailing through the traffic and the clogged air,” I wrote on my second day in Delhi. “A man drops from another time onto the street with his monkey, he has matted hair and is all over the colour of dirt, a lost figure shaken from the Bible. A rickshaw overturns, a boy spits red betel juice in a blood stream to the ground, a woman in green climbs back in, laughing, hides her face.” Then, a few days later, the following announcement: “Hear ye, Hear ye! On this twelfth day of April, of the year 2001, Linda Besner did witness two huge grey elephants parading past her breakfast on Main Bazaar Road, decked out in flowers and glitter and carrying little boys on top of their cloud-splitting shoulders.” I started to get used to some of the cultural differences, like how it didn’t seem to be rude to stare. “I love how everybody watches me blow my nose,” I wrote in my journal between romantic descriptions of the tinkling of women’s ankle bracelets as they crossed the dusty streets. “I feel totally justified in picking it and garishly displaying the sock I’m using as a handkerchief, if they’re so damn interested.” Eleven years later, I have seven notebooks on my desk in Toronto filled with detailed descriptions of what I saw, and zero photographs.

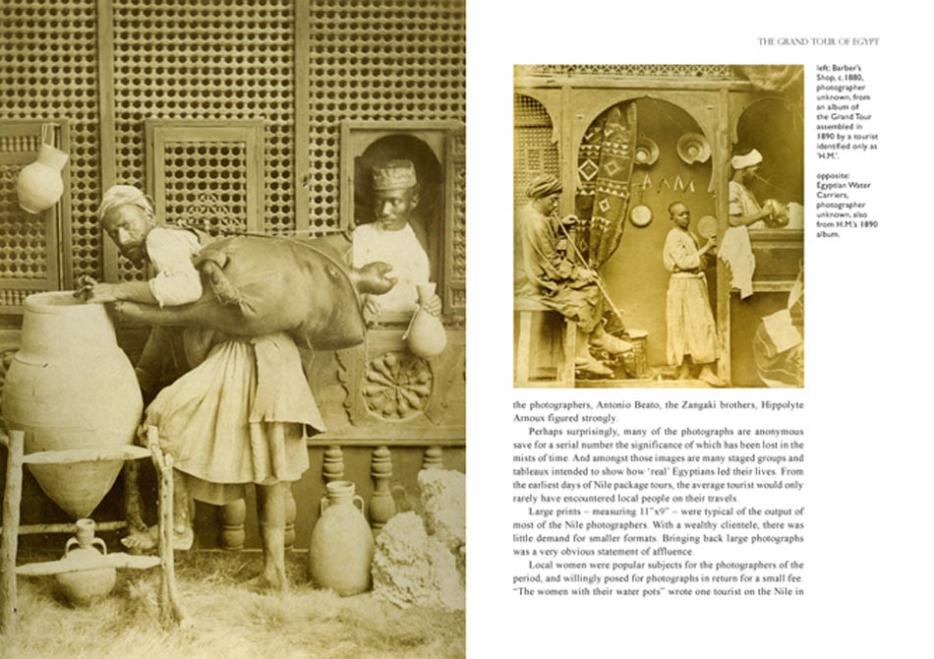

In The Victorian and Edwardian Tourist, John Hannavy describes how travellers to Egypt in the late nineteenth century gave rise to a cottage industry of postcard photographers. The pyramids and the Sphinx were winners, of course, but British tourists were interested in more than monuments. One of the most popular genres was scenes of Egyptians in national costume, posed to look as though they were engaged in authentic Egyptian activities, such as drinking tea at outdoor stalls. “Images which showed ‘real’ Egyptian life were hugely popular with tourists,” Hannavy writes, “although actually experiencing Egyptian culture and life was to be avoided.” One of the pictures Hannavy provides in this section is a study by Hippolyte Arnoux, a French photographer based in Port Said. It’s called “Nubians.” In the photograph, two black men in white loincloths stand awkwardly, while a third sits on the ground between them. All clutch traditional implements—a spear, a bow and arrow—and all three stare uncomfortably off in different directions, away from the camera. Tourists loved it. Hannavy comments, “In a world where global communications were still almost a century in the future, what another race looked like was fascinating in itself. Before embarking on the Grand Tour, few of these wealthy travellers would ever have seen an Arab.”

I sat down on a bench in the Taj gardens and added a few squiggly lines to my drawing to show the intricate patterns of the carved archways. Then two women about my age walked up and sat down on either side of me. They leaned close and put their faces next to mine. Their ears and noses flashed with silver jewellery. I looked from one to the other, but they weren’t looking at me; they were looking at their father, who was holding a camera. “Hey,” I said to the girl in the green sari with white trim, but their father said something else to them in Hindi, and they grinned while he snapped the picture. I never saw it, but I can imagine what it’s like: two Indian women on holiday, and me between them like an irritated Daffy Duck at Disney World. I’m wearing a bedraggled wrap skirt and stained t-shirt with a fringed scarf wrapped around my head, like every other Western kid who goes to India to learn about medicinal herbs. The women got up, smoothed their silk saris, and walked away with a photo to prove how alien and picturesque other cultures can be.