Married people are supposed to share their money.

I found this out a few days after my wedding. My husband and I were eating the misshapen remains of a cheese tray in bed, after the tempest of uncles and hailstorm of aunts had swirled away. The last of the Greek cousins were gone. My mother-in-law, having conjured ice cream for a hundred people out of a freezerless kitchen, and my mother, her finger-joints swollen from pulling apart the maddening layers of ninety-six fuchsia tissue-paper flowers, had escaped back to their own lives. But our guests had left something behind: the yellow-striped card box, teetering on top of a bin of dirty forks.

At the hall, while I was busy identifying the dead body smell as an actual dead body (a mouse, found expired under the snacks table and borne away in a festive napkin), my sister had dressed the box in wrapping paper, taped a purple pom-pom on top, and cut a slit through which our guests could drop their best wishes as well as cheques, gift certificates, and cash. The generosity of our friends and relatives, now tumbling out onto our bedspread, was humbling.

Humbling, too, to take these gifts to the bank and be told we couldn’t deposit them unless we opened a joint account. “Neither of you can cash a cheque made out to both of you,” the teller informed us. “We get this all the time after weddings.”

It never occurred to me that I would share money with another person. I moved in with my partner not long before we got married, and for the preceding ten years, aside from a brief, sad stint at a previous boyfriend’s, I had lived alone. I loved living by myself. In the life I knew, I was dictator and sole citizen of my personal republic. Our national drink was instant Nescafé; our national dish was spaghetti. Our flora was a single valiant cyclamen. Our anthem was silence. Our finances were a ball of earwax tied together with skipping ropes: a mix of magazine and newspaper journalism, arts grants, editorial services, and grant-writing contracts.

But now our friends and relatives had invested in us—literally—as a joint endeavour. It was hard for me to grasp. My family is not much good at marriage, but we are spectacular at divorce. Both sets of my grandparents were divorced, back when such a thing was still scandalous. My parents divorced when I was seven, and they both got remarried and then got divorced again. Our home life reached equilibrium after the demise of my mother’s third marriage, and from what I could observe, the most stable household configuration was a lady, an armchair, and a newspaper. Other elements might come and go, but these three formed a perfect union. I tried to explain this to my husband early in our dating life, when he broached the subject of a future together. It’s not exactly that I don’t want to, I said. There’s just nothing in my experience to suggest that it works.

For our honeymoon, we spent five days camping by the beach, and my wallet was stuffed with receipts: who paid for raspberry ice creams, who bought the hot-dogs, who bought the firewood. Friends inquired, Is this for your divorce lawyers? Meticulous records of the small purchases could hardly address the greater inequities: not only did my husband make twice as much money as I did, I had moved into the house he owned. I paid rent and half the bills, but every time he brought home a block of expensive cheese I had a sinking feeling that I was living a lifestyle I couldn’t afford and didn’t deserve. My husband’s parents have been married for fifty years, and in his eyes, keeping track of whose assets are whose is a purely academic exercise. To me, it seems dangerous to get too comfortable.

As we started sending out our thank-you notes, I began reading The Complete Idiot’s Guide to the Economy. I was looking for a language for the partnership, both metaphorical and actual, I seemed to have contracted. Love is a system of exchange, and cohabitation and marriage seemed to literalize its terms. Home economics is a redundant concept: “economics” comes from οἶκος for “house” and νέμω for “manage.” I wondered if the marquee theories of supply and demand offered any insight into how our household should be run. Perhaps, in dividing up the grocery bills, my husband and I should be Marxist: from each according to his ability, to each according to his need. Or maybe we should spend hedonistically rather than saving for the future. After all, as Keynes famously said: in the long run, we are all dead.

Or perhaps the answers were hidden in the love lives of the canonical Western economists: Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and John Maynard Keynes. Romance is famously a form of lunacy, irrational to the core. But historically, marriage is a business deal. Building a shared life seems to demand a sophisticated form of double-entry bookkeeping, in which a column counting cash and a column counting feelings are somehow reconciled.

*

Adam Smith is famous for two ideas that came to form the basis of free market thinking: that an “invisible hand” hovers over the exchange of goods and services, ensuring their fairness and rendering intervention superfluous; and that if everyone pursues their own self-interest, all will prosper. “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest,” he wrote in 1776. “We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.”

A laissez-faire approach to love has appeal: if naked self-interest could really make for a happy household, perhaps the difficulties of marriage have been oversold. The trick, presumably, is to pretend to be asleep when it’s my turn to make the coffee, and to pocket the cash my husband leaves lying on the dresser. His ornery cat hisses at me and pees in my shoes, and her ill-temper represents for me what economists call an opportunity cost—because of my husband’s pre-existing mean cat, I can’t get a dog. If I ran on self-interest alone, some accident could easily befall her. In terms of romance, it would be advantageous to me to have more trading partners, but not if my husband can also trade with whomever he wants—a clandestine affair is to be preferred over an open relationship. Ultimately, I would want to work myself into the position with the greatest bargaining power by being the one who needs the relationship less. Smith could have designed the modern dating app.

It is possible to dispense with Adam Smith’s romantic entanglements fairly briefly, because as far as we know, there were none. He never married and declared that anyone in love inevitably seemed ridiculous—a sucker. To an outside observer, the feeling is “entirely disproportioned to the value of the object,” he remarked.

John Maynard Keynes is a different story. The thirty-five-year period of prosperity after the Second World War, an outlier that has nonetheless fundamentally shaped our expectations in the Western world, was dominated by Keynesian economics. Before the 1930s, most theorists believed that Smith’s invisible hand regulated employment, and that the market would naturally provide jobs for everyone who needed or wanted them. When the calamity of the Great Depression put millions of people out of work, Keynes proposed a revised role for governments. Unemployment, he argued, happens when people aren’t spending enough money on goods and services sold by their neighbours. The way to get consumers to spend more is for governments to put more money into their pockets. Any government stimulus package that seeks to spend its way out of a recession borrows from the playbook Keynes wrote, the 1936 treatise The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money.

But I’m here to talk about his love life.

The twentieth century’s most influential economist had the face of a swollen eel, so Virginia Woolf said, and they were quite good friends. She also wrote that he looked like a gorged seal with a double chin and a ledge of red lip, “sensual, brutal, unimaginative.” Keynes’s own opinion of his looks was no better. At twenty-three, he wrote to a male lover: “My dear, I have always suffered and I suppose always will from a most unalterable obsession that I am so physically repulsive that I’ve no business to hurl my body on anyone else’s.”

He got over it. And with a statistician’s zeal for spreadsheets, he created an itemized list of the many men he slept with. It reads like a series of detective novels: The Bootmaker of Bordeaux; The Sculptor of Florence; The French Conscript; The Stable Boy of Park Lane. Keynes’s circle, the Bloomsbury group, was tolerant of gay sex, but British law was not. Oscar Wilde went to prison for sodomy when Keynes was twelve. His Cambridge friends distinguished between “Lower Sodomy,” which involved actual sex, and “Higher Sodomy,” when men loved each other’s minds. Keynes himself appeared in a celebrated list: a database of ten thousand case studies compiled by Magnus Hirschfeld, a doctor from Berlin campaigning for the decriminalization of homosexuality. He sought patterns in the physiological and psychological attributes reported by the gay men he interviewed. Can you easily separate your big toe from the others? Hirschfeld’s survey inquired. Are you talkative? Are you logical?

What was logical, at the time, was to marry a woman. In 1921, Sergei Diaghilev’s ballet company mounted a production of The Sleeping Beauty at London’s Alhambra theatre. A Russian ballerina named Lydia Lopokova danced the role of the Lilac Fairy. Her style was unusually robust, even cheeky—she once lost her underwear onstage. She was Georgian London’s manic pixie dream girl, and the public went wild for dolls with her face. Keynes watched her from the audience night after night, and then went around to her dressing-room door and introduced himself.

“Don’t marry her,” Vanessa Bell warned him. “However charming she is, she’d be an expensive wife and would give up dancing and is altogether to be preferred as a mistress.” Lopokova’s finances were indeed in disarray. As a child, she was upwardly mobile: from a lower-middle-class background, she had managed to get free tuition as well as room and board at a dance school by the age of nine, and by the early stages of her career made twice as much money as her father. But by the time she met Keynes, she had weathered twenty years of the vicissitudes of professional dance: ballet politics, endless travel, vaudeville roles alongside bicycle-riding dogs. At thirty, she had been married and divorced from the Diaghilev company’s shady business manager (he turned out to be a bigamist), and the company itself was teetering. She knew she couldn’t keep dancing forever.

Many of the letters Keynes and Lopokova exchanged (hers endearingly misspelled) during their courtship are about money. “Oh! One of the important happenings! Our engagement is extended for eight weeks,” Lopokova wrote of a theatre contract in 1923. “I am quite rich. I will write with tenderness all the expences in the book.” Keynes had given her a special notebook for her bookkeeping. Not long after they met, it turned out Diaghilev hadn’t paid the Alhambra’s rental fee; the theatre kicked them out and impounded all the props and costumes. Loppy, as Keynes called her, went into business for herself, booking gigs in various productions, and mounting some shows of her own. “Tomorrow I shall have my salary, is it not a pleasant thought? I am such a calculatrice nowadays.” Keynes began negotiating her fees with producers, sometimes writing business letters that he signed in her name.

The two married in 1925. For the first half of his career, Keynes had subscribed to the classical economic theory that a laissez-faire market would, when working properly, employ everyone. Keynes now wrote that the market, left to itself, would naturally come to rest in a condition of high unemployment. In the biography Universal Man: The Seven Lives of John Maynard Keynes, Richard Davenport-Hines compares the revolution in Keynes’ approach to economics with the about-face in his sexual life. Keynes seems to have abandoned male partners altogether. The couple’s letters glitter with pornographic coinages: “I taste your buttons,” she wrote; “I want to be foxed and gobbled abundantly,” he replied.

Despite all his friends’ predictions (Woolf considered Loppy an ignorant pleb), Keynes and Lopokova’s marriage was long and happy. The major disappointment was the stubborn non-arrival of children, even though Keynes tracked Loppy’s cycle as meticulously as he had once recorded his lovers. He became an advocate of government oversight to enforce fair pay standards for women in the workforce. She nursed him in his final decade, and then embarked on the kind of free-and-easy widowhood that comes with not giving a tinker’s toot: sunbathing naked in her garden; walking down the street with a shopping basket upside-down on her head; speaking Russian when she got bored of speaking English, whether her interlocutors understood her or not.

What strikes me most now in Keynesian thought is its optimism. Reporting on a meeting with a potential booker, Loppy wrote to Keynes: “I did repeat what you said, noble failure is preferable to cheap success, that financial ruin was not so desperately important.” How fine and freeing to think so. As a unit, Lopokova the artist and Keynes the economist were seen, both by their friends and by historians, as complementary, a surprising fit that made for a stable home life with a bright seam of recklessness.

If I am not behaving lovingly enough, the answer in a Keynesian marriage would be to give me more affection. The love I receive, so the bet goes, will overflow my coffers—I will be spurred to spend it back liberally into the home market. My husband objects that this is implausible and makes Keynes sound like a sop. “If I shower you with more love, won’t you just value my attentions less?” If my husband were married to Keynes, he might retort that currency devaluation isn’t as monolithic as it looks, and besides, the point is to reach full employment. A marriage in which no labour potential is wasted—no opportunity for making each other happy missed—seems a worthy goal.

*

On October 20th, 1918, Fanny Jacobs and Harry Rosenberg, near strangers, were married in a cemetery in Philadelphia. A crowd of over a thousand people, all Jewish immigrants from Russia, cheered from among the gravestones. It was a shvartze khasene, a black wedding, which folk tradition held would protect the community from pestilence. The Spanish flu had then killed over half a million people in Philadelphia alone. Holding a wedding in their resting place would please the dead, elders from the Old World said, and the dead could intercede with God to beg for mercy for the living.

I started this essay in what now feels like the old world.

Our emergency savings are in the joint account we opened with our wedding money. The teller who helped us was named Neena, and it was her first joint account too—first week on the job, she confided. A younger woman hovered over Neena, occasionally pointing out where to click on the screen. When our provincial government declared a state of emergency on March 17th, we spent some of our wedding money on a sack of rice, a gallon of olive oil, and a deep freeze. I’m still confused about the deep freeze—a couple of months ago we were vegetarians, and now we are talking about spending hundreds of dollars on an eighth of a cow in case global food supplies give out. But the deep freeze seems to make my husband feel safer, and in our household’s current economy, even an illusory sense of safety has a value higher than gold.

In the past several years, a spate of studies by North American banks have found that more and more couples are choosing not to combine their finances—a Bank of Montreal survey found that only a quarter of Canadian couples completely pool their resources. There are regional differences: couples on the prairies are the most likely to share everything, and Quebec couples the least. Millennials are far less likely to use joint bank accounts than their parents. When Neena asked for my SIN, I wrote it down and slid the paper across her desk. But reflexively, I shielded it with my hand so my husband couldn’t see. I’ve always been told to keep my personal information secret—no one said secret until you get married.

Of the many conspiracy theories about the pandemic’s shadowy origins and agenda—5G, biological warfare gone wrong, Zuckerberg finally eliminating real-world interaction altogether—it feels to me like a dystopian victory for a particularly narrow vision of nuclear family. No sex unless you live together. Limited contact with friends and extended family. Historically, marriage was an outward-facing arrangement that wove otherwise unrelated groups into mutual-aid networks. Peasants used to sing songs and recite folktales that made fun of married love, as a way of reminding couples who were too wrapped up in each other not to forget their obligations to the wider community. Theologians used to caution married people not to love each other too much—it might distract them from the image of Christ in each other’s faces. But over time, western European and North American culture has idealized an ever smaller, more private, and more self-sufficient unit. At time of writing, my city’s by-laws impose a fine of a thousand dollars for being caught within six feet of anyone from outside my household. When I look out my window, the pods trooping past are like ads for conservative family values—mom, dad, two kids. The model for a virtuous life under current conditions matches most closely with the kind of marriage I was brought up to avoid—insular, isolationist, fearful of outsiders.

In the first few weeks of the pandemic, my sense of myself as a person with an independent existence from my husband suddenly seemed like a fantasy—I couldn’t believe I had ever taken it seriously. It seemed clear that whatever happened to one of us happened to both of us, and any decision one of us made—to touch anything, to go anywhere—was being made for the other. The idea of reckoning up whose money had bought more of the cabbages or lemon concentrate in our emergency box was a dark joke. What future would we be keeping track for? The wider economy was running on the same calculation. Suddenly, it turned out, the imperative to earn a living had been a myth all along—none of that mattered. What mattered was not to die, and the government ordered everyone to stop working and go home. They would simply print money to keep us alive. As an economist commented on Australian national radio, “We are all Keynesians now.”

And yet—these dynamics have a way of reasserting themselves. As people locked down across the globe, the labour exchanges within households have come under heightened scrutiny. The economic impact of the pandemic has fallen disproportionately on women, especially women of colour, as jobs in the service sector have disappeared or become more dangerous. For some couples with children struggling to work from home, the imperative for someone to provide childcare in periods of school closure has pushed the lower earner out of the workforce. And in families in which one or both are still going out to work, all previous cost-benefit analyses that led to career choices have utterly changed—while pay may have remained the same.

*

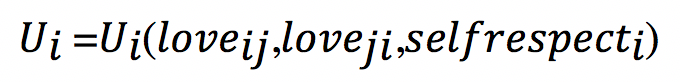

Shoshana Grossbard contends that you can, in fact, buy love.

In this equation, which Grossbard published in 2018, the U stands for “utility,” which is the term economists use for what the rest of us call happiness. The individual’s happiness will depend on an equilibrium between the loving care moving from one partner to the other (i-j) and back (j-i). Loving care might take the form of home-cooked meals and folded linen on one hand, cash and approval on the other. Happiness in a marriage is a function of both love and self-respect, the latter of which is produced under several conditions: recognition of one’s labour competence; the ability to achieve a desired standard of living; a choice about what kind of work and leisure to engage in and when; and an inherent belief in one’s own worth.

Love in lockdown is a paradox in which the value we ascribe to each other’s lives is high, and therefore we seek to minimize each other’s happiness by limiting each other’s freedom. I’ve never wanted to be one of those couples who exercise together, but to avoid going out we set up an exercise circuit that had us running back and forth between the weights in the living room and the skipping rope in the yard. After one of our biweekly grocery expeditions, my husband started coughing. We found a small neighbourhood grocery doing delivery, wrote all our emergency numbers on a sheet by the door, and prepared ourselves for the worst.

Our ability to isolate efficiently is, of course, strongly associated with class. We have the kind of white-collar jobs that can be done from home, and we can afford (for now) the higher prices for local delivery. An apartment building abuts our lot, and I guiltily avoid looking up at its windows as I, the yarderati, get my safe exercise. We wouldn’t be in our current situation without a lifetime of help from our upper-middle-class families, and it is very plain to both of us how little we have earned our good fortune. My husband is still coughing, but over the past month no other symptoms have developed—our immediate fears have subsided. Instead of helping my husband get organized for the months to come, I’ve been distracted, lying awake planning out what I would have done if I were still alone in my old apartment. Being loved means I am no longer solely responsible for taking care of myself, but being cared for makes me feel less competent—I respect myself less.

Even though Grossbard goes by @econoflove on Twitter, she doesn’t tend to use the word “love.” The equation itself is derived from the work of another economist, Charlotte Phelps. Grossbard argues that what Phelps calls love looks an awful lot like what she prefers to call work-in-household (represented here as H):

Here happiness is a function of the exchange of work between partners, combined with L for waged labour, X for consumer goods, and S for leisure time. Phelps, writing in 1972, argued that although a woman who becomes a housewife receives payment for her loving care through her husband’s provision of material goods, this exchange stops short of making love a market commodity. “No currency, money or approval, can buy love,” Phelps wrote. Why not go all the way, Grossbard asks, and say that the rewards for loving care (work-in-household) should be monetized? “Providing more legal support to exchanges of loving care for money is a key to more fruitful negotiations among partners and potential partners,” Grossbard writes.

In Richard Thaler’s 2015 book Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioural Economics, he talks about his affection for honour boxes. You see them at highway farm stands or unattended campsites, nailed to a wall or a post: you can drop coins or bills in, but you can’t take them out. For Thaler, it’s a nutshell explanation of human nature. Enough people will voluntarily put money in the box, even if no one is watching, to make it worth the farmer or the parks service’s while. But if the box were easy to open or steal, it wouldn’t be long before someone did.

Before the crisis, my husband and I had set up rules to govern who paid for what proportion of which things in our household. There are plenty of apps designed to help couples keep track but our method is old school—a blackboard in the kitchen, on which each of us is supposed to chalk up our expenditures. The beauty of this honour system was that it allowed us to cheat on each other’s behalf. When I decided to buy a fancy jam that wasn’t on the list or pay more than my share for gas on a trip to visit friends, I could fudge the numbers.

Now we don’t seem to have any system. My husband set up the grocery delivery on his credit card, and depending on which news he’s been reading, the box arrives full of pie and ice cream (it is hopeless, everyone we love will die) or cabbage and canned sardines (we will all live long enough to lose our jobs in six months). We’re still figuring out what proportion of these emotional purchases I should be responsible for. One of the major contributions of behavioural economics is the distinction it draws between Econs and Humans. Econs are the purely rational agents found in economics textbooks: they buy, sell, change jobs, start businesses, and plan for the future in the most beautifully ordered way, always choosing perfectly between available options to maximize their own utility. Humans are the dazed, impulsive, occasionally altruistic characters you meet standing in a panic before supermarket displays of six kinds of apples. In decisions that involve any kind of self-control, a Human is actually two selves trying to act as one. There’s one self-trained on the future and one who sees nothing but the present. Human marriage is four selves trying to act as one; it’s like doing the dishes from inside a horse costume.

One of the dominant metaphors for marriage in economic literature is the firm. Or The Firm, as I started to think of it, for the 1993 Tom Cruise movie. Whoever is behind on their share of cooking and vacuuming is letting The Firm down. McDeere was also supposed to stick with The Firm until death did them part. The idea is that marriage vows are in fact an employment contract, albeit with fuzzy terms. As always, exploitation is a strong possibility. In the 1950s male breadwinner model of the household, wives are the workers and husbands the cigar-waggling industrialists. Much Marxist-feminist ink has been spilled on the inequality of this relationship, and even though the proportion of contemporary partnerships that fit the male breadwinner model is low—in 2015, Statistics Canada reported that both partners reported income in 96 per cent of couples—the gender wage gap means that inequality follows most women home.

Intra-household bargaining matters to the politicians and bureaucrats running the economy. In part, for its role in driving buying patterns. Some theorists argue that the home is no longer comparable to a firm, because these days it’s not a site of production, but primarily a site of consumption. Although there is one essential product, an adequate supply of which is considered necessary for the smooth running of a country, that is manufactured at the discretion of the home firm. Families are the factories where children—i.e., future workers—are produced.

When I lived alone, I had no one else’s income with which to compare my own, and success was defined as paying my rent and bills every month. Now, I am keenly aware that my husband makes more money than I do. Neither of us wants this fact to be meaningful. There’s lots to explain why we aren’t bringing home the same amount of bacon, since we do different jobs in different sectors. But it’s tricky to maintain an equal relationship when it’s so easy to quantify how unequally the outside world perceives your value.

*

“You know that I have sacrificed my whole fortune to the revolutionary struggle. I do not regret it. Quite the contrary. If I had to begin my life over again, I would do the same,” Karl Marx wrote in 1865. He was corresponding with Paul Lafargue, a protégé who wanted to marry one of Marx’s daughters. “I would not marry, however. As far as it lies within my power, I wish to save my daughter from the reefs on which her mother’s life was wrecked.”

Jenny Marx, née von Westphalen, was born into the Prussian aristocracy. She died in London after a lifetime of dodging bill collectors, begging from friends and relatives, pawning her belongings, and seeing four of her seven children die of poverty-related diseases. Karl and Jenny were childhood friends; he had studied with her father, who was himself a proto-socialist. Her family was nonplussed by the match, however, mostly because Marx was terrible with money. His happy-go-lucky spending habits at university (he was president of a drinking club and chose the most luxurious lodgings in town) drained his own middle-class family’s resources, and Karl and Jenny’s engagement was a negotiation that lasted seven years. Eventually, Marx agreed to sign a contract waiving Jenny’s liability for any debts he had incurred before their marriage.

There would be plenty more debt to come. They married in 1843, when he was twenty-five and she was twenty-nine, and moved to Paris, where Marx wrote radical articles under a pseudonym. Within a year, a police commissioner knocked on the door, and Karl was expelled on the charge of atheism (actually for rousing sentiment against the Prussian royal family), with twenty-four hours to leave the city. He left, and Jenny stayed behind with the baby to sell the furniture to cover outstanding rent and bills. This pattern was repeated with dreadful monotony over the next forty years. Every time a wealthy relative bailed him out, Karl promptly rented living quarters fancier than he could afford, spent whatever was left on furniture, and was quickly broke again. The family was in rags and lived close to starvation. When Karl tried to pawn what remained of Jenny’s family silver, he was nearly arrested—how could such a vagabond have gotten hold of silver with the Argyll crest?

The Marxes serve as a chilling example to anyone contemplating marriage to a writer. Early on, Karl got an advance for the book he was writing on “political economy.” Jenny rejoiced that the book would soon make her husband’s reputation, usher in a socialist paradise, and yield enough royalties for the family to live on. Instead, Karl pretended to be two weeks away from finishing the manuscript for sixteen years. For most of this time, he hadn’t even started. The publishers demanded their money back as Karl spiralled off into more and more research, endlessly broadening the scope. There was so much more he needed to read and think about, sitting at his desk in the British Museum while Jenny fended off creditors.

All this paints Marx as a terrible husband. Yet, as the Prussian spy assigned to peep through the Marxes’ windows attested to his superiors, Karl was quite a cozy person to have around the house. He played stagecoach with the children, letting them tie him to a row of chairs and whip him; when he and Jenny went out, he was a good dancer. A friend remarked that he had seldom seen so happy a marriage, “in which joy and suffering were shared and all sorrow overcome in the consciousness of full mutual dependency.” Like Keynes, Marx was described by friends and strangers as hideous—short and squat, his rampant beard reeking of cigar smoke, his coat buttoned wrong. Jenny, like Lopokova, was considered beautiful and elegant, though eventually her face was scarred with smallpox, the doctor’s bill for which Marx described as “hair-raising.” It is also not the case that Jenny was Karl’s victim. She was an ardent socialist who considered her own health and safety secondary to the propagation of her ideals. “Where could we feel more at ease than under the rising sun of the new revolution?” she asked in her memoirs.

Even the Marxes, however, could not live on ideals alone. In 1850, pregnant and desperate once again, Jenny sailed to Holland to plead with Karl’s wealthy uncle for more money, to no avail. “I believe, dear Karl, I will return home to you with no results, fully deceived, mauled, tortured in mortal fear. If you knew how I yearn for you.” Meanwhile, Karl was impregnating their housekeeper, Lenchen. The baby was given up for adoption, and Karl’s friend and patron, Friedrich Engels, claimed to be the father. Jenny left no evidence of her private thoughts on Lenchen’s condition (the maid had come to Jenny from her own family back in Germany and was more like a sister than a servant), but historians speculate that it was nearly impossible for Jenny to have been entirely oblivious—the entire family lived in two squalid rooms.

We do know that by the end of her life, her husband’s book still unfinished, Jenny Marx was so depressed she could barely get out of bed. Her mother died, and with Jenny’s inheritance the family managed to rent adequate housing (again, it wasn’t long before the money was gone and they were out on the street). In her memoirs, Jenny wrote of this period, “We were sailing with all sails set into bourgeois life. And yet there were still the same petty pressures, the same struggles, the same old misery, the same intimate relationship with the three balls of the pawnshop—what was gone was the humour.” Poverty wasn’t funny anymore. Engels, the hero of any Marx biography, had gone to work for his father at the hated family mill so that he could support the Marx family while Karl completed his important work; now Engels cleared their debts and put them on a yearly allowance.

Jenny did not live to see the success of the book for which she had sacrificed her health and peace of mind. Not because she died before it was published—Das Kapital came out in 1867 and Jenny lived until 1881—but because the book was a flop. It was not until later that the book found its unrivalled place in the history of economic thought.

The Marxes, in short, did not manage a Marxist marriage. In emotional terms, neither of them seems to have got everything they needed, and in financial terms they certainly did not. There’s an authoritarian streak in me that whispers the appeal of rigid planning to enforce fairness—left to my own devices, I am well aware of how often I fail to consider the needs of others. For a household to be run in such a way that everyone feels in control of their own labour, and yet the mutually desired amounts of clean laundry, cooking, and sympathetic listening are produced, a manifesto may well need to be drawn up. Whether the Marxes each gave according to their ability is harder to assess. Who can be certain how much love they really have to give?

*

Adam Smith was born at the tail end of the last outbreak of bubonic plague in western Europe; between 1720 and 1723, half the population of Marseilles died. In Smith’s lifetime, smallpox also devastated the Indigenous populations of the Americas, in part due to its deliberate use as a biological weapon. While Karl Marx was living in Soho, the neighbourhood was the locus of an eruption of cholera; 23,000 died of the disease in England that year. John Maynard Keynes lived through the Spanish flu.

Marital norms also fluctuated during these economists’ lifetimes. The eighteenth century saw the rise of the love match in western Europe, a trajectory that mirrored the rise of the market economy and increased independence from the family network. While Marx sat in the reading room of the British library, the British upper classes were sentimentalizing the role of married women as the moral and emotional core of the household—the thin edge of the wedge we would now call affective labour. Keynes, who died in 1946, lived long enough to see sex take up a central place in the popular conception of a good marriage.

Among the many unknowns of how the coronavirus pandemic will reshape our societies is how the psychological and material effects of lockdown will affect people’s desire for partnership. As a lifestyle choice, marriage is objectively in decline: a United Nations report from 2019 found that, worldwide, people are marrying later or never, and divorcing more often. In the U.S., data from the past few years project that a quarter of today’s young adults will stay single for life. Some studies suggest that, contrary to popular belief, married women are sadder, sicker, and shorter-lived than their single counterparts.

Marriage has always been a risky business, containing, as it does, scope for exploitation, violence, and the general misery of spending time with someone who makes you unhappy. In an age when companionship, for those able to exercise some control over their exposure to others, is more scarce, the calculations about what kind of household formation to seek become more complicated. The utility of a good marriage is even higher, while a bad marriage poses a greater threat than before. Quarantine conditions intensify all the dangers of a bad relationship, and advocates are calling the rise in domestic violence a pandemic-within-a-pandemic. The limited social contact outside the home means reporting avenues are blocked, and ongoing confinement makes it easier than ever for abusive partners or parents to monitor and control the communications, movements, and finances of victimized members of the household.

Medically speaking, solitude is the ideal state. Early on, experts suggested that even people who shared a home should limit how much they touched each other. And solo living can allow for greater agency in choosing a desired level of risk tolerance. For those choosing to date during the pandemic, romantic dealbreakers can be incompatibilities of hand hygiene, or of willingness to roll the dice on attending a birthday party. Financially speaking, too, our society tends to place a high value on financial independence. But the economic imperatives that have driven partnership for millennia could set many searching for traditional forms of cooperation as we enter an era of global financial hardship. During the Great Depression, the divorce rate fell—people couldn’t afford to separate. Now, as then, the social forms our emotional lives take carry the imprint of more widespread crises not of our making, created by systems most of us only dimly understand.