It’s so familiar, it’s almost comforting, isn’t it? Apple have just introduced a new iPhone and, shortly thereafter, have broken sales records and seen their stock pushed to record highs. It reminds me of a conversation about smoking I once overheard in a teacher’s lounge: no matter what happens, at least you always have your cigarettes. Apple is our tobacco.

Ever since the iPod overtook the Walkman in the brand-name-turned-cultural-object sweepstakes, the company has just sort of been there. Not only are they credited with saving the music industry, publishing, and, when they finally get around to it, TV, their products have become shorthand for the cultural changes engendered by modern, mobile tech. “iPads are the future of reading” the headlines read, and it’s only a matter of time until a Cosmo cover will feature the display copy “38 ways the iPhone will make your sex life mind-blowing!”

Those who marvel at Apple’s remarkable success have always roughly fallen into two camps. On the one hand, there are those who believe such ubiquity is a triumph of the shallow: that it’s mostly marketing, style over substance, and the simplistic disguised as ease of use. On the other side are those who feel it has something to do with the sacred. These people believe in design as divining, and that Apple have tapped into a way of doing things that is both right and natural.

Neither are right, but nor are they entirely wrong. In actuality, though, Apple has become part of the current historical moment not simply because of marketing, design, or even quality, but because they understand something else entirely: normativity.

When something is normal, it just is. When something is normative, it’s supposed to be what “just is.” It’s like the normal, if the normal walked around with an imposing bodyguard. And Apple’s products are not simply compelling or well-marketed or just better. They’re normative, too.

Making itself normative is something Apple has come to excel at. You can see it in its marketing that pretends competition doesn’t exist, and that the only really logical way to do something is to use an Apple product. Helping matters along is their naming scheme, which has taken to using known nouns—phone, TV, message, or cloud—and simply attaching that digital ‘i’. Now, there are phones, there are iPhones and, as someone once remarked as I pulled out my Sony handset, there are things “that are like iPhones but aren’t iPhones.”

When something becomes normative, it feels inevitable. Ever used an iPhone and then found a PC strangely “unintuitive”? On the surface, it seems like a sign of Apple’s design brilliance—until you ask yourself when you’ve ever pinched something to get a closer look at it, or swiped upward to see more of a news story. But that’s how normativity works: it makes things seem “natural” because it sets the standard of how everything is judged. Whether through design or dumb luck—or both—Apple have tapped into that same thing that makes us look into mirrors and wonder we’re masculine or feminine enough, or wonder, if at 35, we are where we’re “supposed” to be in life.

Given that much of this is a result of Apple simply making better stuff for us to use, it all seems pretty okay. That is, at least, until we examine what it does to how we think about the world. After the iPhone maker’s recent legal victory over Samsung, GigaOM writer Mathew Ingram cautioned us with a post titled “Apple may have won, but that doesn’t mean software patents aren’t evil.” Just think about that for a second. It says, “the good guys won, but this thing that they happened to enforce and rely on is evil.” Only in a world in which Apple are the assumed purveyors of the good and true could such a doublethink-laden headline be written.

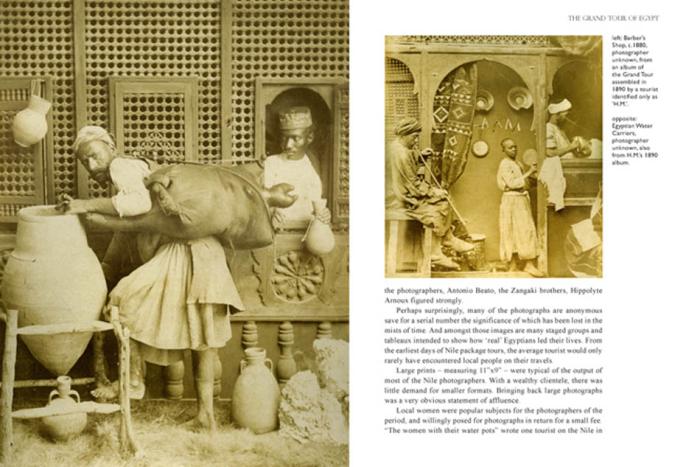

It might seem a bit conspiratorial, but it’s an odd coincidence that the economic and cultural system that so valorizes Apple also works the same way. Free-market democracy is also a seemingly inevitable norm, as the discourse around the Arab uprisings of last year are testament to. And rather than alternatives seeming just bad or undesirable, they have become almost unimaginable. Both a Windows Phone and socialism seem similarly absurd propositions to most people at Starbuck or Tim Horton’s across the country.

It’s why Apple, in the process of becoming the most valuable company on earth, have also become the quintessential American company. America, after all, is the only country on earth that doesn’t have a country code for its websites. They simply end in .com, as if there are normal, regular websites, and then lesser, “international” ones. That’s what normativity does: it makes a situation seem as if it was simply supposed to be, while encouraging you to forget that there were other choices along the way.

“So what?” you might rightly ask. What difference does it make if a company and their ideology become ubiquitous—so much so that we can now have Apple-esque thermostats? Well, that’s just exactly it. When something becomes normative—whether gender roles, national identities, or the connections between one company and consumer technology—thinking differently becomes harder. The weird, the quirky, the radical—i.e. what Apple purportedly once stood for—gets pushed to the side.

After all, Apple may have won. But that doesn’t mean they’re not evil.