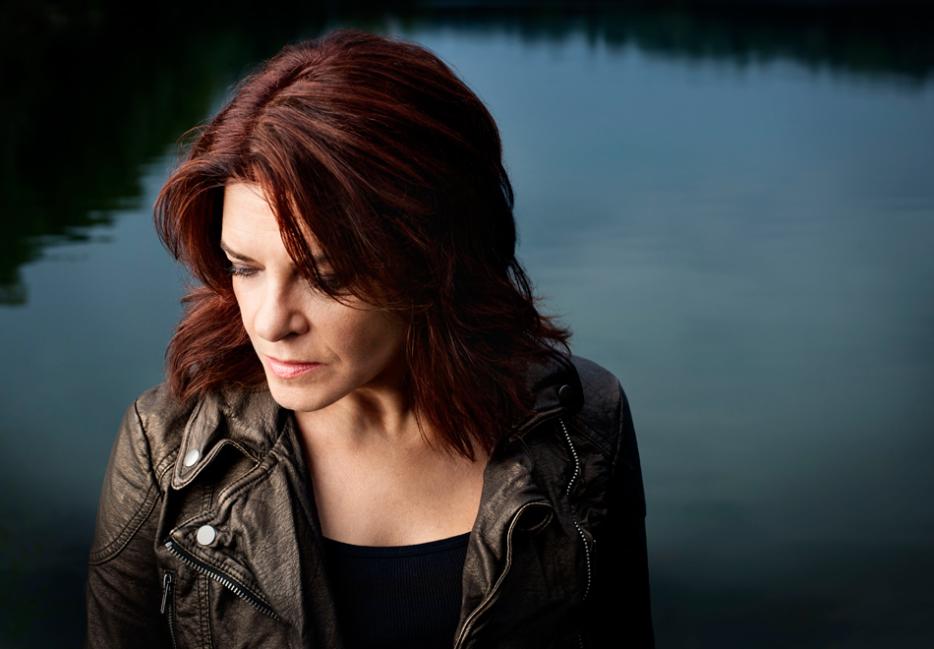

In the Oxford American’s most recent Southern Music Issue, Rosanne Cash writes about her father Johnny’s long-time bassist Marshall Grant and his wife Etta:

“The drama, love, schisms, and reconciliations of Dad and Marshall’s relationship were played out for the most part in public, but no one saw the heartbreak of Mom and Etta’s inevitable separation after my parents’ divorce … Etta put a stool in the hall outside her kitchen next to the wall phone so that she could sit and have long conversations with my mother every day. In one conversation Etta recalled my mother saying, in reference to the Carter Family traveling with my dad’s show, ‘Etta, I’m a little concerned about Anita.’ Etta said, ‘Vivian, you ought to be a little more concerned about June.’ Prescient, to say the least.”

A continuous transition between distinct modes of history—the grand narratives that guide traditional rock biography (a singer’s feuds with his sideman; the archetypal romantic duet) and the ones (such as intimate conversation between two women at one remove) that usually don’t—is what gives Cash’s new album The River & The Thread its sense of anti-nostalgia. The forest is forever contorting itself around the trees. “Etta’s Tune” manages to describe a 65-year marriage with the barest strategic sentimentality: “Now don’t stare into those photos / Don’t analyze my eyes / We’re just a mile or two from Memphis / And the rhythm of our lives.” When Cash sings the couple’s morning greeting one last time, she sounds deliriously weary: “What’s the temperature, darlin’?”

Cash uses this method intuitively: she grew up in California by way of Tennessee, became the closest thing to a new-wave country star, recorded 11 #1 singles even as she felt increasingly alienated from Nashville conservatism. (Elsewhere in the Oxford American piece, she mentions a Grand Ole Opry host who mocked her hot pink Comme des Garcons jacket, with its “hugely exaggerated shoulder pads.”) The River & The Thread emerged from the Southern trips Cash and family took to restore her father’s childhood home, an ambivalent inheritance; “as much as my dad’s legacy is something I cherish, it’s a burden with a lot of moving parts,” she told the New York Times Magazine. The tension finds form in the extraordinary control of her singing, which moves through phrases at a pace that suggests apprehensive yet unhurried wisdom. During songs like “The Long Way Home,” her voice seems to be gathering a coat around itself.

In my own hindsight, the fulcrum of Cash’s discography is 1990’s stark, sundered Interiors, the first album she produced herself. Her collaborator and husband Rodney Crowell was on his way to ex, and she was moving to Manhattan, where her family still lives. Perhaps the new city spurred her introspection; the country charts still prize narrative more than most other genres, but not stories like these. Last month, my friend Brad Nelson wrote:

“The imagery of Interiors is bracingly literal, all of its drama internally staged. Tracks one and three are titled, respectively, ‘On the Inside’ and ‘On the Surface,’ the latter detailing the outward calm and domestic regularity of a relationship; this tranquility, of course, is used to obscure whole annihilated dimensions within. When Cash refers to events or people outside of her characters, like chilling newspaper stories, or the substance of memories from which her characters are irrevocably withdrawn, they feel almost alien and hostile to the scene. They move through the songs with the intoxicated drift of ghosts.”

With “When the Master Calls the Roll,” Cash inverts herself: here, instead of rendering temporality unrecognizable, loss brings the sweep of events into marmoreal clarity. The Civil War ballad’s narrator imagines a young widow meeting her Unionist husband again beyond death: “Oh, Virginia, whence I came / I'll see you when I'm younger / And I'll know you by your hills again / This town from six feet under.”

As Hazlitt’s own Carl Wilson noted, Cash draws a parallel between personal and national discord: Appalachian fiddles and New Orleans funeral brass, Rodney Crowell and her second husband John Leventhal, they all second a plea that “the union be made whole.” But the reconciliation envisioned is hardly triumphant. While most songs like this contain war as an individual tragedy, heroically shouldered, the characters in “When the Master Calls the Roll” cling to the hides of roiling historical forces, and paradoxically it ennobles them. A roomy shroud is all they hope for now.

Not every song on the album sounds so absolute; I understand Carl’s lament that the Leventhal production sometimes sounds too restrained, “too tastefully professional and measured for the material.” Was Cash thinking of her father, the prolific minimalist who ended up wearing a mythic ancient’s garb anyway, as if his singles had been etched into desert rock rather than vinyl? (Cash senior did not seem to take that Rick-Rubin-assisted outlaw-preacher image entirely seriously.) Better question: how many popular musicians keep accruing sophistication at the cusp of retirement age? Now we’ve got two from the same family. At the beginning of The River & The Thread, Cash invokes a string of non-synecdoches, transfiguring dull memory into mysterious language: “a feather’s not a bird, the rain is not the sea, a stone is not a mountain but a river runs through me.”