Prince drives me to apologetics, in the Christian sense—I feel compelled to understand every new funk throwback, hymnal ballad, or ghastly foray into jazz fusion, figure out how these components fit into the shimmering whole of his discography. (The greatest songs tend to resist that compulsion with their capaciousness; you might as well try to explain sex, and in many cases, you would be.) As his creative peak in the 1980s becomes ever more distant, though, it sometimes feels like a chore. The visionary who seemed to program drum machines in his own erogenous pocket universe has settled for self-quotation, indulging his crankiest reactions and fretful musical atavism.

So when Prince announced his rapprochement with Warner Bros. earlier this year, regaining control of his back catalog at last, acolytes like myself began fantasizing: a Purple Rain 30th anniversary edition, of course, presumably reissues of the Sign ‘O’ the Times concert film and other lost relics, maybe even choice apocrypha from that fabled song vault? But releasing two new albums with Warner this week promised something else, a certain relaxation towards the world beyond Paisley Park.

Not that his ‘90s wanderings don’t fascinate in their own way—you just need to delve judiciously. I’m fond of 1994’s contract-discharging Come (every track has a one-word title, like some oblique Pet Shop Boys tribute), which starts with an 11-minute-long number, attempts techno, and broods on fields of “crucified dandelions.” “Pussy Control,” the tale of a female pimp who industriously hires all her former school bullies, is both Prince’s bluntest proposition to hip-hop and a ludicrous fantasy all its own: “I met this girl named Pussy, at the club International Balls / She was rolling four deep, three sisters and a weepy-eyed white girl driving a hog.” The 1996 triple album Emancipation contains two albums of very good music, ranging from delicate ballads like “Soul Sanctuary” to the outright club beats of “Sleep Around” and “The Human Body,” but it sags badly in the middle. Prince engineered each disc to be precisely 60 minutes long, becoming more obsessive about the circumstances of a given record’s release than whichever songs ended up on it.

Art Official Age, one of two new Prince albums released this week, was supposed to be different. The lead single “Breakfast Can Wait” circled back to his axiom of funk, but with a slinkier stride than the guy had displayed in years. Its meal-interrupting premise echoed sex jams past in terms suited to a middle-aged Jehovah’s Witness. The music video featured a woman in Prince drag. And although he wrote and produced everything himself, as usual, there is evidence of outside contributions, negotiations with the zeitgeist. The opening title track alone cycles through five or six separate breakdowns, from “dubstep” to “imminent Rapture.”

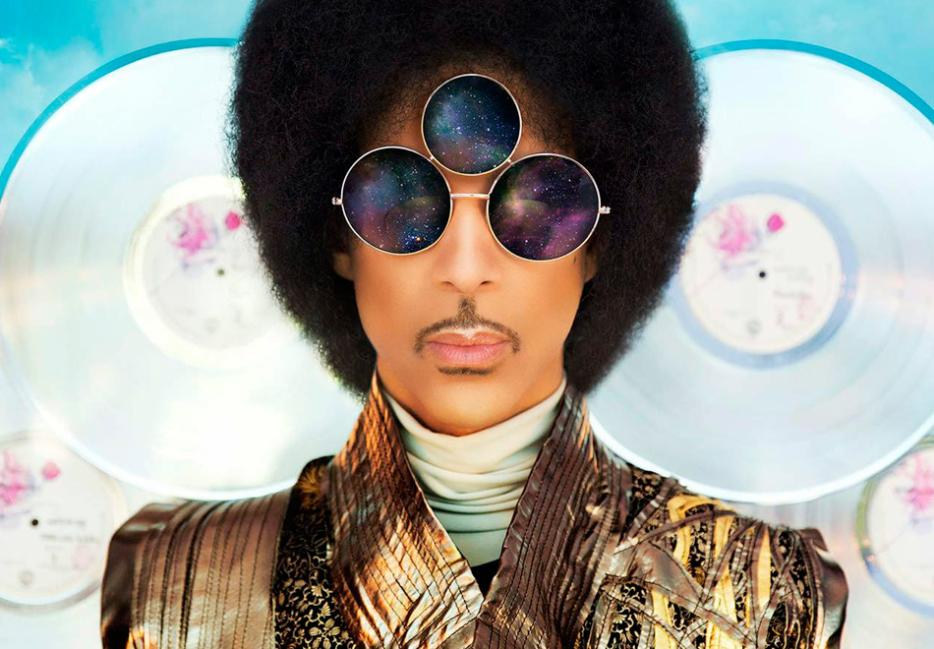

Did a record company’s oversight help his music? Maybe it would’ve curtailed the hideous variety of recent album covers (Art Official Age looks like a Raelian recruiting pamphlet), but few label executives could be as controlling as Prince himself. What he misses, I think, is a decent foil to grind against.

He’s always delighted in warping the conventions of pop songcraft, though, whether stripping the bass from “When Doves Cry,” coiling into the extreme concision of “Kiss,” or fucking around with a sampler for “Batdance.” Here, the new single “Funknroll” mutates, too—vamping to a minimalist beat before introducing maximally sped-up Linndrums and the kind of synths that accompany a fictional spaceship launch. Does all the modernization hang together? Well, the constant vocal effects are an aesthetic of sorts.

The British singer Lianne La Havas also appears on Art Official Age, not singing much. Her precise accent intones a series of futuristic spiritual affirmations: “There are no such words as ‘me’ or ‘mine.’ Words of this nature were introduced into society as a control mechanism which systematically divided the subjects first individually and then as a collective.” Prince’s religious songs used to be paranoid and bizarre; now they’re just inane. His most convincing revelations come through the body: “Seemed that I was busy doing something close to nothing / But different from the day before / That’s when I saw her, when I saw her / She walked in through the out door.” Art Official Age manages the same with a few lovely ballads—“every book I read said that I would meet somebody like you,” the dauphin murmurs on “Breakdown”—but there’s something straitened about its consistency, a narrowness. My friend Brad described the tracklist as “evocative husks of former Prince songs.”

Did a record company’s oversight help his music? Maybe it would’ve curtailed the hideous variety of recent album covers (Art Official Age looks like a Raelian recruiting pamphlet), but few label executives could be as controlling as Prince himself. What he misses, I think, is a decent foil to grind against. Mostly his ‘80s peers are dead, like Michael and Whitney, or plying the boomers, like Bruce. The shrunken legal department at Warner Bros. surrendered. He struggled to sustain a collaboration with any protégé distinctive and strong-willed enough to defy him: The Revolution, Morris Day, Sheila E, they all left eventually. And aside from their contributions to official Prince records, it’s a pleasure to hear his compositions filtering through other sensibilities; “Nasty Girl” would sound rather less decadent lacking Vanity’s bored tones. For all his pitch-shifting role-play, Prince is an auteurist, uncomfortable with the routine sampling and automated production teams of pop qua pop. Even Warner contrived to do him one favour, demanding edits to the project that ultimately became Sign ‘O’ the Times—it was at this point supposed to be three discs long—and yielding an unimpeachable sequence.

If pop encourages the shorthand of iconic gestures, Prince made his ambiguity itself the spectacle. He was male and female, numinous and sensual, gay and straight, black and white (fancifully, melodramatically, in Purple Rain, and figuratively, in his choice of band lineups). Listening to his music, you begin to think whiteness and maleness might be soluble.

Sign, Sign, Sign. I thought of it again while listening to the two new albums, or half of them at least, since 3rdeyegirl (Prince’s backing band for PLECTRUMELECTRUM) are so bland that I hardly thought about anything. Art Official Age has plenty of terrible lyrics, even discounting his suggestion that the kids should put their phones away and put some clothes on; we woke up in this purplish collectivized future, and people are still acting like the Rolling Stones fans who once abused him for wearing bikini briefs? But I would probably sound idiotic describing “Starfish and Coffee” to someone as well, no matter how much it charms me. The critic Michaelangelo Matos once wrote that Sign ‘O’ the Timesachieved sprezzatura partly by following apparent mistakes: “A power outage in [Prince’s] basement studio robbed ‘The Ballad of Dorothy Parker’ of its high end, rendering it muddy and hypnotic.” On “If I Was Your Girlfriend,” he dreamed of abandoning masculinity itself, like some item you lose and then forget to miss: “Would you let me wash your hair? / I mean, could we go to the movies and just cry together?”

If pop encourages the shorthand of iconic gestures, Prince made his ambiguity itself the spectacle. He was male and female, numinous and sensual, gay and straight, black and white (fancifully, melodramatically, in Purple Rain, and figuratively, in his choice of band lineups). Listening to his music, you begin to think whiteness and maleness might be soluble. Several years ago, a Hilton Als essay recalled the sense of betrayal when Prince began wearing relatively conservative suits: “Maybe Prince was trying on power like he’d try on garters or fishnets. But he didn’t jettison the suits—or his suit—fast enough to win me back. And if it hadn’t been for the love of others, I might never have forgiven him. So until I met him, I saw Prince only through other people—when I saw him at all. He was like a bride who had left me at the altar of difference to embrace the normative.”

The outfits have gotten feyer again. (Remember that turtleneck-and-sceptre combo?) But Als discerned the same tendency that leaves me a little bereft after hearing Art Official Age, despite its elan, its snatches of joy, the aggressively weird sequencing. Aside from “Give me back the time, you can keep the memories,” which sounds like Leonard Cohen haggling with God, Prince too often gives certainty the ring of complacency. I sneakingly love the fact that, on his 1990s albums, any two songs might originate years and years apart, destabilizing the entire linear chronology we music writers use to enforce lists and periods and canons. Prince came from a birth certificate, but I’ve always thought he must appreciate that word’s liminal connotations, must revel in a state of not yet being something, of beautiful indefinite becoming.