The last time anyone paid attention to a sentence with the words “Iranian regime” and “tweets” in it, we were all horrified by Tehran’s crackdown on protesters in the days and weeks after the absurdly rigged 2009 presidential election. That election, to the Ayatollah’s enduring regret, cemented Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s tenure for another term instead of allowing what the Iranian system recognizes as a “moderate” to win.

Fast-forward four years, and another “moderate” is in power anyway, because it turned out that Ahmadinejad was, above all else, a terrible policymaker. And while nobody should be expecting a normalization of US relations with Iran, Nixon-to-China-style any time soon, there are signs that the change in leadership has meant something more than different stationery in the offices.

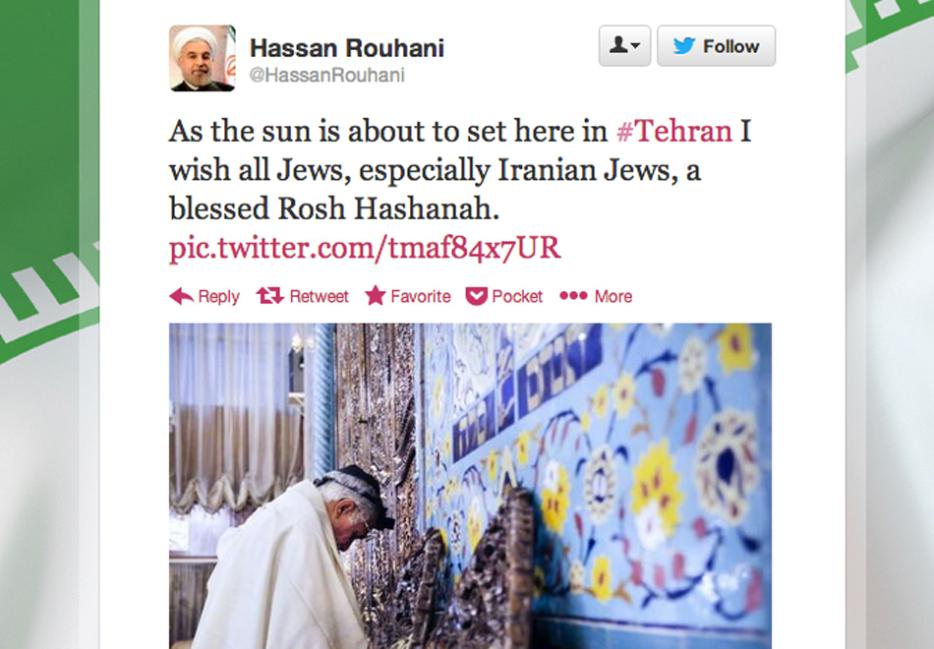

Exhibit A, somewhat trivial edition: Members of the Iranian cabinet, including President Hassan Rouhani, sending out Rosh Hashanah greetings and incidentally adding a “good riddance” to Ahmadinejad’s legacy of denying the Holocaust. “Somewhat trivial” because they’re tweets, the lowest-effort symbolic gesture imaginable, but the optimist could see a genuine attempt to engage again with the wider world, even—gasp—the Jews in it.

These more conciliatory notes come only a month after the Iranian president got his first taste of worldly outrage by calling Israel’s occupation of Palestine a “a sore that has been sitting on the body of the Islamic world for many years.” As the New York Times noted, this narrower focus on Israel’s settlements rather than Israel itself is actually what passes for moderate language in these circumstances. Your mileage may vary.

Exhibit B, somewhat more substantial edition: Rouhani and the people around him seem to be leaning away from the Assad regime in Syria, even as hardliners try to push the government toward more direct aid for Assad despite the Syrian government’s chemical weapons use.

(Meanwhile, it increasingly appears that chemical weapons were used on Assad’s orders, in a fit of temper. Another example if needed why having dictators is a bad idea.)

It’s not clear what US strikes on Syria would mean, as far as Iran’s politics go. Mehdi Khalaji argues that strikes on Syria would strengthen Rouhani’s hand against hardliners, but the logic seems to miss a beat somewhere. Despite the differences of ethnicity and language, it’s hard to believe that US strikes against Syria would be terribly popular in Iran, even as Rouhani’s allies try to symbolically tie Assad’s use of chemical weapons to Saddam Hussein’s use of sarin against Iran.

Just as it would be a mistake to view the Iranian leadership’s support for Assad as some deep fraternity between the Iranian and Syrian people, it would be a mistake to dismiss any notion of Muslim solidarity, and the deep suspicion of US motives, that does exist.

In Iran we’re being reminded that regardless of the caricature of the Ahmadinejad years, it’s a large, populous country with its own unique internal politics. Nobody is going to mistake the Iranian leadership for a B’nai B’rith dinner any time soon, but there are reasons to be hopeful that Iran and the US can someday start talking again—unless and until the pendulum swings back to the hardliners’ favour.