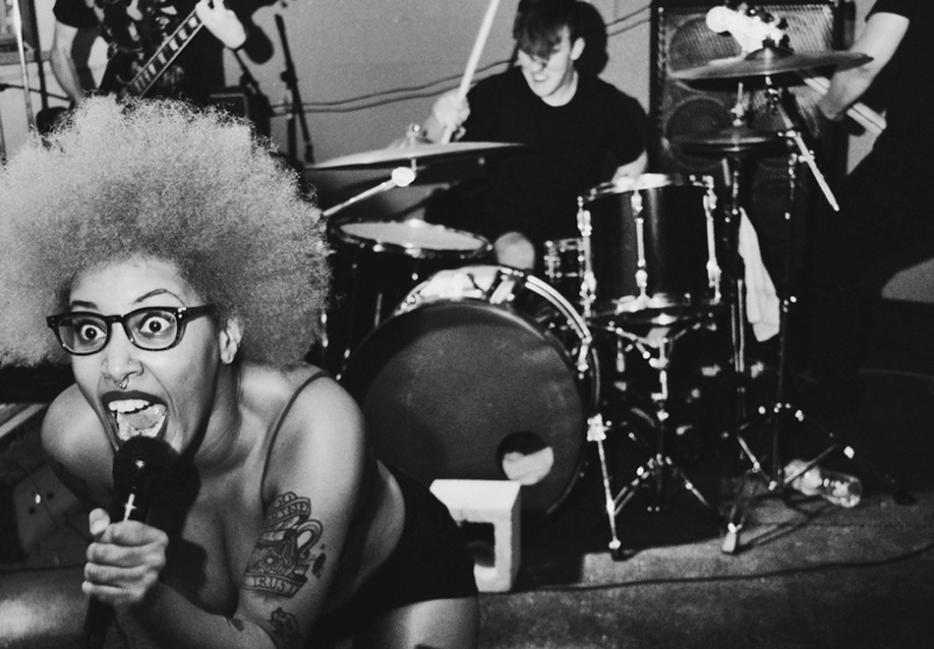

Last fall, Kayla Phillips, vocalist and songwriter for Tennessee’s hardcore/grindcore band Bleed the Pigs, published a piece with Noisey about her experiences as a black feminist with a natural inclination towards extreme music (“I’m more of a womanist,” she told me recently, “just to differentiate that I address intersectionality to ensure that people are aware that there are two sides that make me who I am”). She wrote:

My anger as a Black woman fronting an aggressive, politically charged hardcore/metal band with DIY punk ethics is somehow too much for [some listeners]. White punks screaming about the same politics, the same fucked-up shit, and even about racial issues and injustices they don't even particularly face, are wholeheartedly accepted, never questioned, never told to tone down, and never told to relax. No matter how justified I am, or how down for the cause they are, they're put off by my very valid rage. Why is that? What is it about a Black girl doing the same shit white men do that makes them feel like it's too much? How am I the only one being labeled too aggressive in a genre that is all about aggression?

Despite the global appeal and presence of heavy metal culture, widespread online distribution, and increasing awareness among a diverse audience, there remains great resistance to discuss ongoing sexism, racism, and other issues that can potentially dissuade fans from actively participating in the subculture. “I don’t know why it is so hard for people to understand that not everyone is just like them,” Phillips told me. And Phillips isn’t alone; other artists and journalists are questioning the pervasiveness of discriminatory practices and beliefs within a musical culture that, ironically, not only boasts of its “inclusive community” (in which membership is predicated on fandom and not gender, ethnicity, or sexual orientation), but also, because of its underground status, places an emphasis on fan participation and economic support in order to create and distribute music that will never, and doesn’t want to, receive true mainstream commercial attention.

*

Despite both carrying reputations for rejecting societal norms, more often than not, using “heavy metal” and “feminism” in the same sentence is bound to raise some eyebrows. For anyone who remembers the 1980s hair metal craze and the ensuing complaints about the representations of women in Motley Crue and Poison videos, or the impossibly high number of women KISS bassist Gene Simmons allegedly had sex with during the band’s heyday, it makes total sense that the genre and the ideology mix as well as oil and water. And metal’s tense relationship with female representation is hardly confined to the past: The fact that, in the 21st century, a national music magazine publishes an annual issue and sponsors a national tour dedicated to physically attractive female metal musicians, doesn’t bode well for the argument that heavy metal can be a liberating and empowering culture for women.

Once broadly defined as encouraging the emancipation and promoting the equality of women, the ideology of feminism now describes a plethora of different narratives that contribute and broaden conversations that challenge patriarchal structures. Heavy metal is one of those structures—a genre that originated from a predominately white, male, and working-class ethos in the swing of 1960s de-industrialized England and America. Several heavy metal historians have focused on the popularization of the music by socially discontented young men who were drawn to bands whose subversive lyrics supported listener’s disenchantment with mainstream conformity. Though they rarely feature in the history books, female fans also experienced the same feelings of alienation, and quest to challenge the mainstream. While seldom mentioned, women, such as Coven vocalist Jinx Dawson, whose 1969 Witchcraft Destroys Minds and Reaps Souls predates 1970’s self-titled Black Sabbath (often considered the first heavy metal album), were also active consumers of the music.

But Dawson, as a performer, was an exception: Documentaries on the early days of the heavy metal scene, such as the 1981’s Iron Maiden & The New Wave of British Heavy Metal and 2008’s Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey either ignore women musicians, such as Girlschool, who emerged in England in 1978, or refer to them as anomalies, such as former Warlock vocalist Doro Pesch, one of the first women to front a metal band.

When I asked how she felt she was perceived by Bleed the Pigs’ audience, Phillips said that she has yet to experience what the metal community boasts—an inclusive community. “I’m definitely seen as a black woman first. I definitely feel that.”

In Heavy Metal: The Music and its Culture, one of the first books to examine the genre from a sociological perspective, Deena Weinstein argues that while the origins of heavy metal were not pointedly misogynistic, an anti-feminist sentiment has been present since the early days. In heavy metal, O’Brien says, the term feminism “… is used as a dirty word and an accusation, which is interesting to me… Some people might want to uphold a traditional view of heavy metal as the bastion for exerting male masculinity, but I can’t imagine that it has anything to do with the larger conversations about sex and gender.” The sonic and philosophical traits suggest a masculine aggression, which has little to do with the reality that listeners from all genders carry not only the same traits, but share the propensity to enjoy those feelings within music.

Despite this history, there are still women, like Phillips, who find that heavy metal fits their feminism. “I am a feminist with the understanding that there are multiple feminisms that women engage with between women and men,” says Alia O'Brien, vocalist, flautist and organist for Toronto’s Doom-metallers Blood Ceremony and a PhD candidate in Ethnomusicology at the University of Toronto. She credits her studies on postcolonial feminism and her understanding of the three waves of feminism with shaping her choice of music, and her songwriting. “I have my own way of approaching it and obviously it plays into my life onstage, beyond the stage and the relationship between my stage persona and my everyday life, and I’m always thinking of what it is to be a feminist in the context of when I am. I think that it's important that there is a space for people to have multiple perspectives based on their personal experiences. Feminism is not this theological project that infers that we will all eventually come to the same conclusion, and I don’t think that it needs to happen. I think that just because we are having conversations about it, that it's permeating the realm of metal music journalism and creating conversations among metal fans and social media, is important.”

*

Male metal journalists, despite the undeniable fact that women fans actively participate within the scene, still use outdated sexist tropes to determine exactly why they are there. Andrew Bansal wrote about female fans in a 2015 piece on Metalassault.com:

Scoring a backstage pass is of utmost importance, and eye-candy takes far greater precedence than the music. I am yet to meet a chick that goes to shows purely for the music and has no interest whatsoever in developing friendly and/or sexual relations with the musicians. I do not expect or hope to find one any time soon and shall make no attempt to do so.

In December of 2014, Scott Vogler founded the term #Metalgate (which was inspired by Gamergate). Brett Stevens, the founder of the website Death Metal Underground, and one of his writers, Corey van der Pol, supported the campaign, writing a number of articles that derided “social justice warriors”—those who wrote about feminism, sexism, and racism, taking a liberal perspective within the metal scene. They also interviewed Vogler, who said, “you can recognize them by their most obvious attribute, histrionics. If you dare mention a word about something they take personally you will see a display unlike any other.” Believing that “social justice warriors” were trying to inject mainstream society’s problems into an insular community designed to be offensive and provocative, Stevens urged readers to join a movement to push them out.

Lurking a private email listserv for academics involved in heavy metal studies, Stevens took screenshots of posts and private email messages written about #Metalgate from female metal journalists and posted them online, after which readers began attempting to contact the journalists (myself included) via Facebook and Twitter. In the conclusion of a “call to arms" post, Stevens wrote, “ Death Metal Underground will continue its mission of providing quality metal information no matter who gets offended and decides we are Satan. We will save you the trouble: we are the Satan to your pharisaic interpretation of God that excludes truth in the name of obedience, and we will always oppose you.”

The #Metalgate hashtag on Twitter stopped trending almost as soon as it appeared, but the paranoia inspired by the idea that journalists and artists who wanted to explore how to make their localized metal scene more inclusive were an actual threat to the foundation of heavy metal was confusing at best.

“They need to understand intersectionality,” O’Brien says. This would allow them to comprehend how a diverse set of perspectives talking about heavy metal is beneficial to its growth, not a hindrance. “I have the privilege of going to school so this is a no-brainer for me, but for people who don’t have access to that literature or that way of thinking, there is a misunderstanding that feminism is just one thing, or that all of our issues are the same. I do think that it is important to find areas of commonality because it does strengthen our support across different platforms, but I think also to understand that different people have very different struggles—my struggles are not going to be the same as other people, so we can’t speak to each other; we have to listen. That’s also important.”

*

When I asked how she felt she was perceived by Bleed the Pigs’ audience, Phillips said that she has yet to experience what the metal community boasts—an inclusive community. “I’m definitely seen as a black woman first. I definitely feel that.”

Phillips does believe that open communication with others about the role her personal beliefs and her experiences have in who she is as a performer makes a difference. “I think that my (white) bandmates understand through wanting to learn. When we are on tour, we have discussed issues and they will admit that they hadn’t even considered some of the stuff I tell them,” she says. “We bring out a lot of black women and trans women at our shows and they are always up at the front, so they see that their presence there means something, that they are reacting to something important.”