In April 1974, a left-wing group of Portuguese military officers eased the country’s decrepit Estado Novo dictatorship from power. The coded signal to begin the coup was a radio broadcast of Portugal’s entry in the latest Eurovision Song Contest, “E Depois do Adeus”; as people spontaneously united in the streets of Lisbon, handing carnations to insurgents, their unheard anthem was a flowery ballad about “your empty place, your absence in me.”

This was the most audacious meeting between pop music and political secrecy I could think of until midnight last Thursday, until Beyoncé smuggled out the fourteen songs and seventeen videos also known as Beyoncé.

The utter lack of marketing was the marketing. It wouldn’t have worked so spectacularly, though, if she hadn’t made her best album yet, kinky and eerie and vulnerable—like the closest parallel that comes to mind, Janet Jackson’s The Velvet Rope, a perfect record. All those iTunes sales measure more than mere commerce. When Beyoncé appeared last week, it seemed like everyone who happened to be online was giddily tweeting jokes about it, brushing away eyebrow ash after watching that “Yoncé” clip, marveling at somebody horny enough to render a new pronunciation of “surfboard.” The lady in question suggested that she wanted to recapture the “immersive experience” of Thriller, that fabled land called Monoculture, with MJ as its king over the water. And it turns out that a monocultural moment might be made lovely by brevity, spared from oversaturated exhaustion or controversy over controversy over controversy. For all the stealthy panache, Beyoncé announced itself in a manner that was pre-digital, even pre-modern. Queen Bey decrees thou shalt listen.

The carping began immediately, too. Actually, Tumblr boy-pedants rushed to clarify, Radiohead or David Bowie or some other white rock artiste did this first. (“Dicks are always happier winning a completely insignificant argument than merely participating in a serious one.”) They may have tried. But they didn’t manage what Beyoncé’s done. Amidst a long-term marginalization of black popular music—for the first time in half a century, not one African-American musician will top the Billboard Hot 100 this year (not counting featured artists, which would make the situation slightly less depressing), while in 2004 they ruled it without interruption—she forced an R&B album where black womanhood is never muted or invisible onto the charts.

“I’m climbing up the walls ‘cause all the shit I hear is boring / All the shit I do is boring, all these record labels boring,” Beyoncé spits on “Ghost.” I don’t hear any ennui here. She probably spent a month in her luxurious secret headquarters sequencing the tracklist. Unlike Justin Timberlake, whose recent gestures towards grand cohesiveness had the wearying torpor of continental drift, Beyoncé really does feel like one long sinuous composition, a full-body liminal zone. Whether poised above trap hi-hats, buoyant disco or slinking Timbaland beats, her voice commands the stage. On the spare “No Angel,” she adopts an ethereal falsetto; “Superpower” reaches a far lower register playing off Frank Ocean, who sounds like he’s trying to sing without swallowing a mouthful of wine. Beyoncé raps well enough to embarrass glorified hook boy Drake, not that his “good girls” fixation wasn’t already embarrassing. He should study “Blow,” which celebrates at least three different ways to give women head.

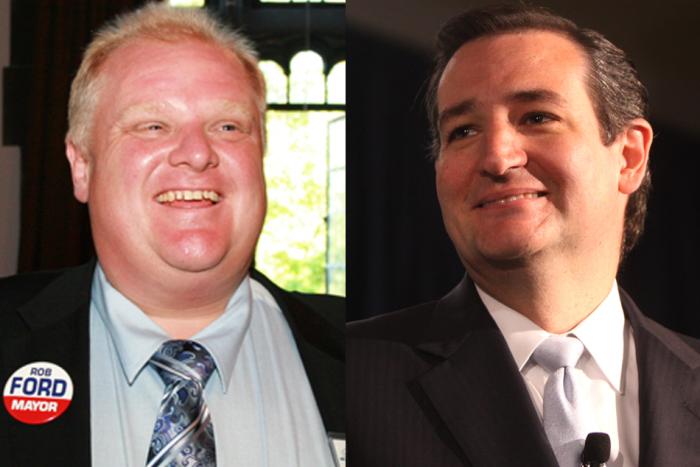

At times, the virtuosity almost becomes alchemical. With “Halo” and now “XO,” Beyoncé is the only person who can get me to enjoy Ryan Tedder’s production style (think Leni Riefenstahl arranging Glee). Borrowing Drake’s usual team, “Mine” curls sonic tropes I’ve always found morose into something elemental and mysterious. She makes a kinda-goofy-looking fellow well into his baffled-dad period as an MC sound like the greatest fuck in the world, perhaps more so for his familiarity: the lust that suffuses Beyoncé is the conjugal variety, another thing not often heard on the radio, relishing exhibitionist limo sex within the intimacy of marriage (or the loving relationship of your choice and configurations).

Beyoncé even found a rare TED talk worth listening to. “Flawless” prominently samples the novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s speech “We should all be feminists,” to wit: “We teach girls to shrink themselves, to make themselves smaller.” But then Beyoncé snarls “bow down, bitches!” and declares “flawless, I woke up like this,” which to some people contradicts her quotation. In a bizarre Slate post, Amanda Hess wrote: “The fetishization of the candid only increases the demands on women’s looks … Beyoncé may be exposing how ridiculous this notion is, but we’re still meant to believe that she really does ‘wake up like this.’” Leave aside the fact that pop stars have been boasting facetiously since vaudeville—Frank Sinatra didn’t really believe he exercised unlimited agency over every aspect of his life. This is such a pinched reading, precise and superficial at the same time. How could you watch the Afro-punk video for “Flawless” and not wonder if “ladies, tell ‘em, I woke up like this,” might be rather broader in its scope?

Mythology aside, pop doesn’t usually begin revolutions; at best, it glancingly anticipates them. So, no, Beyoncé didn’t undo capitalist means of production while breaking nearly every rule about music promotion. You’re not going to hear Angela Davis in the club. What we might hear, if we’re lucky, are irresistible jams by a woman who works Josephine Baker looks mercilessly, identifies more and more with feminist cultural politics, and likes the aesthetics of a firebombed cop car. During the “Mine” clip, a couple facelessly makes out, “YOURS” and “MINE” stamped on each other’s faces. I wish that had been my introduction to semiotics.

Some of us get picky about ballads, unless they open on a line like “let me sit this ass on you.” In its teasing hold-and-release, the way it slowly dances up on you, how Beyoncé takes sly delight from vamping “I’ve been a bad bad bad bad bad bad bad bad bad bad bad girl,” “Rocket” harkens back to Prince’s most lascivious love songs. But it also reminds me of his glorious “Mountains,” or David Byrne pleading “sing into my mouth”: that depth of communion between two people, daring to imagine futurity in a world that seems terrifying or diminishing or merely endlessly distracting. “Been having conversations about separations and breakups / I’m not feeling like myself since the baby, are we gonna even make it?” Beyoncé worries elsewhere. And yet: You look so comfortable in my skin. Who knew her muse had it in him?