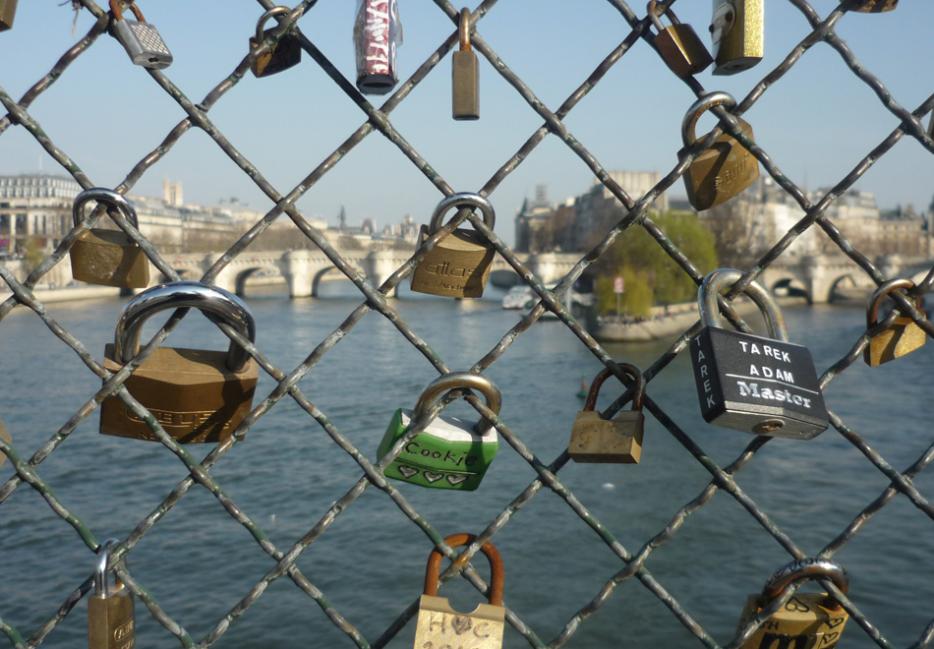

Part of the Pont des Arts collapsed this month under the weight of everybody doing tourism all wrong.

About 100 years ago, a Serbian man and a Serbian woman fell in love. But then the First World War happened, and the Serbian man went off to fight, and fell in love with someone else. The Serbian woman never got over it, and died. Other Serbian women from the same small town, Vrnjačka Banja, were jolted by the fatal effects of lost love and started writing their names and the names of their loved ones on little padlocks, locking them to a bridge in the town where the couple met.

Cute. Lovely.

A few decades later, Serbian poet Desanka Maksimović wrote a poem that bolstered the practice in Vrnjačka Banja, and then in 2000, Italian novelist Federico Moccia wrote a popular novel that also focused on the love locks, inspiring people to do the same thing on Rome’s Ponte Milvio. The practice then spread to other cities tourists tend to think of as romantic, such as Florence and Dublin.

Mostly, though, to Paris, and the super-romantic Pont des Arts.

But because of the way people travel, and the way people think about travel, it was no longer cute or lovely. It became a nuisance, and two weeks ago, a chunk of the bridge buckled under the weight of all that whimsy—the second time the locks, estimated to weigh as much as two semi-trailers, have crushed a part of this UNESCO World Heritage-recognized bridge.

You couldn’t ask for a better symbol of the effect of tourism done wrong. At its best, tourism is an extraordinary economic, cultural and personal force, one of the most unadulteratedly positive effects of modern technology. But done wrong, it can destroy. Orlando is not a city. Florence is intolerable every month of the year. As far as I can tell, the only time you can enjoy Venice is between 6 and 7 in the morning.

I was speaking with Lord Malloch-Brown recently, a former Deputy Secretary General of the UN and now a tourism advocate. One of the worst examples of tourism done wrong, he says, is the Maasai Mara, an extraordinarily popular national park in Kenya, whose environmental assets—wildlife, flora—have been deemed so valuable to the government that it’s hurting the Maasai themselves.

“There’s this historical scar of colonialism, where the Maasai feel they were turned off their land,” he says, “and they haven’t had their land rights recognized to this day, because they clash with the wildlife requirements, tourism and otherwise, and authorities who don’t want the Maasai back on their land, which encroaches back into these parks. The Maasai want to grow wheat, and apparently it’s an absolute environmental killer of the conditions you need for wildlife.”

And so, instead of being able to grow crops to feed themselves, the Maasai, in both Kenya and Tanzania, are poor. I was walking through Moshi recently, and noticed the distinctive Maasai in their colourful robes and tire retread sandals. They were picturesque among a sea of the majority Sukuma and Chaga people, who wore Western clothes and looked more or less like folks look in North America and Europe. At dinner with a Chaga woman that night, the Maasai I’d spotted earlier came up in conversation. She told me that when she was a child, her mother would tell her stories about the Maasai, saying that if she was bad, a Maasai would get her—it’s a common practice, she said. The Maasai are the bogeymen there, gorgeously dressed but poor, beggars on the streets of cities and towns, trying to make whatever they can off the only thing they seem to have left: the fascination of Europeans and North Americans who like how African they look. Another upshot: the Maasai villages tourists visit, fabricated affairs that put the people on permanent display, posing for pictures and recycling their actual cultural practices on cue and by rote, a production-line approach to Unique Travel ExperiencesTM.

If you’ve ever stood in line at the Louvre, paid for a ticket to Disneyland, or tried to get your own Diana picture at the Taj Mahal, you’ll have experienced a variation on the theme. None of it’s pleasant, and all of it is due to travellers’ misunderstanding of one of the fundaments of travel: you do it to experience something different, not the same things as everyone else. There is, of course, huge value in community—in cultural overlap and mass popularity. But one of the virtues of travel is that it takes you both outside yourself, and outside your community. It’s meant to introduce you to new communities, to lift you up and out of the very concept of community, and let you look upon it from beyond the walls. My perspective on celebrity, for example, has never been the same since going to South Korea and seeing everyone go crazy over K-pop acts and songs that to me seemed undifferentiated both in style and content. This goes for anywhere you travel: as you watch people get excited over this or that person who glows with an aura undetectable to you, you start to see your own admirations in a different light.

Of course, it goes far beyond celebrity. Taking yourself out of yourself, away from your home and everything that’s familiar to you, is what gives travel its power to transform. And everyone going to the same places and doing the same things defeats that entirely.

People who travel to Paris and lock their love up on the Pont des Arts enjoy the idea that they’ve done something recognizable, something they can come home and tell their friends about, and have a reasonable expectation of hearing, in response, Oh, we did that too. That’s a reinforcement of the status quo, not the expansion of it—without which, travel is just sitting on the couch in a different country.

And as we’ve seen in Paris, this sort of travel is not only destructive to our experience of it, but to the places themselves. As Malloch-Brown puts it, travel done this badly is “destroying assets that are impossible to restore.”

They can fix the Pont, as they probably already have done. But if these tourism hot spots—Paris, New York, Venice, the Maasai Mara, Orlando, Phuket—continue to grow as they have (and all the ones whose numbers I’ve been able to check are hitting record visitor highs every year; Orlando’s approaching 60 million)—continue to be the focus of our increasingly massive global travel habits, the effect will be very much like a magnifying glass on a bird’s nest on a sunny day.

“There is a steady process underway of a depletion of the environmental capital of the asset, that is usually a non-renewable environmental asset,” Malloch-Brown says. It’s a point of view increasingly popular at the highest levels of the travel and tourism industry. I met Malloch-Brown at the annual summit of the World Travel and Tourism Council, a body of 100 of the highest powered and most influential members of a sector that is responsible for $7 trillion in trade every year. And this year, everyone was talking about non-renewable environmental assets. Not just forests and whatnot being trampled by too many visitors, but the very essence of places such as Venice and Florence—the reason people want to go in the first place, and the reason all these corporate bigwigs who operate airlines and hotels, cruise lines and car rental behemoths, make all their money. If Venice ceases to be lovely, Florence glorious, and Paris romantic, these people stand to lose a great deal. “If you look at it through that kind of twin accounting ledger,” says Malloch-Brown, who was there to speak on a panel called “Travel and tourism: a force for good in a problematic world,” “sometimes it may be better to wait until you’re going to do it properly, rather than use the economic justification to do it badly.”

But as we wait until all those large ships bank and turn to point themselves in the right direction, there’s something we as travellers can do, too: remember the Pont des Arts. Go somewhere none of your friends have gone, and bring back a genuinely new story for a change.