Leonard Cohen’s house is not easy to find. But nothing on Hydra is.

Street names are difficult to locate, and the houses don’t have numbers. The Greek island juts upwards, roads and alleyways wind around steep stone steps without railings. There are no cars or even bicycles allowed. The only transportation you’ll see are mules and donkeys (another reason to watch your step).

There’s uncommon commotion stepping off the Aegean Flying Dolphin ship as a hundred or so travelers find our feet on solid land. Donkey drivers load suitcases onto the sad-eyed beasts of burden. The scene is loud and disorienting for a little while, and then suddenly very quiet.

I stop and look around, distracted by a pack of stray cats grazing at a plate of fish bones some kind Hydriot has left for them, and by the overhead view of the port: a horseshoe-shaped stage for decades of writers and artists.

The cafés and bars of the agora come into view, all arranged in a semicircle around the Aegean Sea. So do the whitewashed houses with their red roofs dotting the green and grey mountains. It looks just like the old footage in the Netflix documentary Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love. It’s like stepping into an archival photograph.

As I get my bearings and try to spot the street leading to my pension hotel, I spot a crinkled flyer for something called the Hydra Book Club. Spotting the Greek text first, I squint and see it’s also in English. “WHAT ARE YOU SEEKING?” it asks in all caps. “WHY NOT COME HERE?”

*

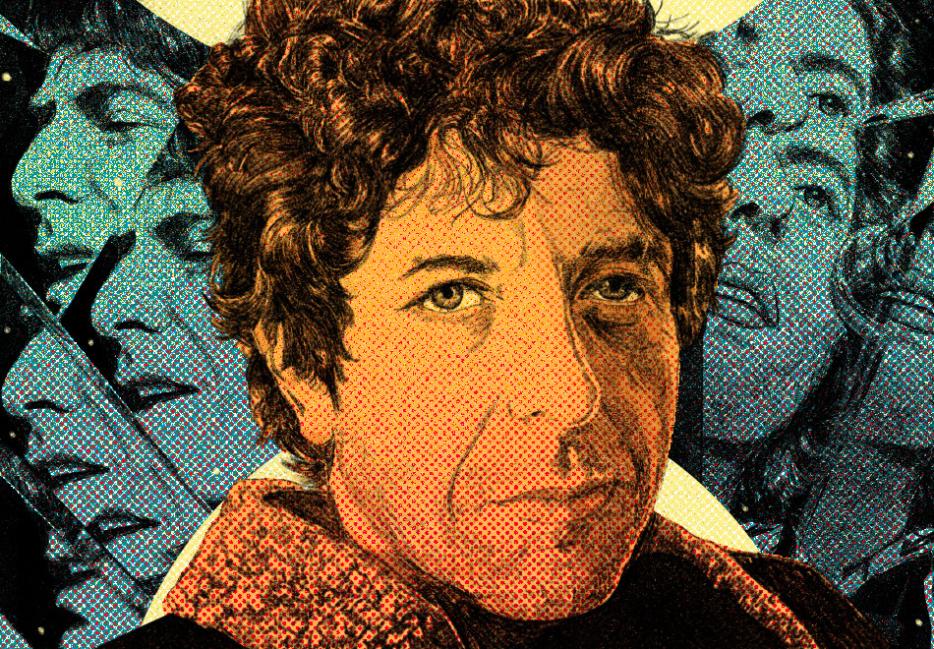

When Leonard Cohen first stepped off the ferry here in 1960, he probably didn’t know how important this small island would become to both his work and his mythology. What he found was a thriving foreign artist colony that fed his early ambition long before he was established as a musician. He also found one of his most famous muses, Marianne Ihlen, who would inspire his work and letters right up until his 2016 death.

But Cohen has always had a deep connection to the places he’s inhabited. One of his great skills is finding the universal in his specific experiences, and so he’s written his locations into his work. He sings about the place by the (St. Lawrence) river in “Suzanne” and the music on Clinton Street all through the evening in “Famous Blue Raincoat.” There’s a monument to Cohen at the Chelsea Hotel in New York, where he famously rendezvoused with Janis Joplin on an unmade bed. And even when he retired from music to become a Buddhist monk, Mount Baldy Zen Center became his legendary refuge.

Hydra is where Cohen first started to take writing seriously, and so it frames many of his early notebooks and letters (occasionally signed from Leonidas). Many of these are currently on display at the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Everybody Knows exhibit. At the Toronto museum’s biographical show, there’s a set of his I Ching coins, a practice he became enamoured with during his Greek years, and the giant metal key to the Hydra house he bought with a $1500 inheritance from his grandmother and returned to throughout the ‘60s—the same one I had such trouble finding this past October.

The ‘60s hit Hydra’s foreign colony like they did other artists of the era. There was plenty of sex and drugs, not to mention gossip and never-ending glasses of retsina. Cohen infamously wrote his second published novel Beautiful Losers in a fever dream of speed and intense heat and very little nourishment. You can read it in the prose.

But Hydra was a spot of respite for Cohen, which led to his unique productivity. In a letter to his mother from when he first arrived, on display at the AGO, he describes his daily routine:

I get up at 7:30 every morning and work for 3 hours. Then I go down to the port for a breakfast of milk and bread and honey. This is famous honey; the ancient poets sang about it . . . I sun for a few hours, then lunch on artichokes, cheese and roe and then the whole island goes to sleep for a few hours, I work for another two hours after siesta and then I wander down to the port & talk and watch the fishermen repair their nets and learn Greek. All in all life is orderly and sweet, always complying with the old ideal “A sound mind in a sound body.”

*

I’ve tasted the famous honey. The poets were right to sing about it.

It’s my first morning on Hydra and I’ve ended up at a portside cafe called Isalos, which I’ve been told by the people at my hotel has the best Greek breakfasts on the island. The menu is filled with decadent spreads of cheeses, breads, cakes and pastries, but the best ones are made for two people and I’m here on my own. So I opt for fruits and yogurt, which is not usually my thing, but I’m in Greece. It’s worth it—thick and cold and refreshing, it's nothing like the yogurt in Canada, not even like the Greek yogurt sold in grocery stores. More importantly, it comes with a full little jar of honey, which slowly drizzles over the bowl in perfectly sweet little globs.

Fending off a persistent wasp, I glance over to the next table. A couple is sipping iced coffees and eating croissants while a carousel of people come over to say hello. One older gentleman with a mop of grey hair and British accent sits across from them and starts singing in Greek. Another woman comes to take a selfie with them. It’s a hint of the old social scene I’ve read about, where artists and bohemians gathered to drink and chat.

Striking up a conversation, I learn the man is one of the owners of the family-run restaurant. So I tell him about my brief and unfruitful search for Leonard Cohen’s house. Leonard’s children Lorca and Adam still often come and stay there, he says, as does their mother Suzanne Elrod. They’re treated like locals on the island, and they like to lay low. Adam has occasionally given gentle hints that the restaurant owner should stop sending tourists to the house.

It’s easy to see why the Cohens would want some privacy while they seek a connection to their father, who the Everybody Knows exhibit hints was somewhat absent during their childhood. In his early Hydra years, Cohen was a father figure to Marianne Ihlen’s child, little Axel, but Adam and Lorca later spent many summers there.

Adam Cohen, a musician himself, has made the Hydra house his own hub. He’s recorded some of his own and his father’s posthumous music there, and the video for “Moving On” takes the viewer right inside the sparsely furnished living room. But the more recent archival work, including Leonard’s early unpublished novel and short stories A Ballet of Lepers and the AGO exhibit, have been done without his children’s participation. They’ve been feuding with the Leonard Cohen Family Trust over control of his archives.

Cohen kept his letters and notebooks because he was confident that they might be worthy of studying someday, but he never made himself easy to know. Always looking to find universality in his specific experiences, he often seemed like he was performing in his life too. That’s evident in Michael Posner’s recent Untold Stories oral history book trilogy. Many who knew him describe the experience of talking to Leonard the poet, not Leonard the person. His dry wit, his ladies' man image, his biblical allusions—it often felt like persona.

The new glimpses offered by the posthumous archival releases have revealed a darker tinge to his unparalleled mix of the sacred and the profane—a fascination with guns and violence, humiliation and control. From A Ballet of Lepers, “A Short Story On A Greek Island” sets a story against an artist colony backdrop and ends in an act of gendered violence.

So, it’s hard to know what you might find stepping in Cohen’s footsteps.

There’s a famous photo of Cohen from Life Magazine in 1960. He’s sitting under an old olive tree at Xeri Elia Taverna, also known as Douskos (named after the family that owns it), and strumming a guitar while surrounded by expatriates. Leaning against him is Charmian Clift, an Australian writer whose novels Peel Me A Lotus and Mermaid Singing detail everyday life in Hydra as it was discovered by artists. This was years before Cohen was first dragged onstage by Judy Collins to sing his debut song “Suzanne,” and some historians like to claim it as his first-ever public concert.

Douskos is still operating and still in the family, feeding generations of Greeks and travelers heaping servings of moussaka and fish soup. Walking into the big open courtyard slightly recessed from the action of the port, it's easy to imagine Cohen and his friends sitting right there. The tree still grows, and the guitar is still on a hook inside the restaurant—apparently the same one that Cohen played, having grabbed it right off the wall.

There are no monuments to Cohen—the tree and the tavern have enough history on their own—but there is a Cohen poem on the menu. “They are still singing down at Dusko’s / sitting under the ancient pine tree,” he wrote in 1967, apparently not as good at identifying tree species as he was at poetry. “In the deep night of fixed and falling stars / if you go to your window you can hear them.”

The beating heart of the foreign colony, a prime setting of Clift’s Peel Me A Lotus, was Kastikas. It was where artists would sit and kibbitz for hours, whiling away a day after swimming or trading rejection letters deep into the morning. A short jaunt from Isalos next to a clock tower that echoes throughout the whole island every hour, the former grocery store is now a bar and cafe called Roloi. This is where Leonard Cohen fans from all over the world have been descending on Hydra periodically since 2002.

The Hydra gatherings are organized by the Leonard Cohen Files. A somewhat primitive-looking message board started in the mid-‘90s, the fan site was fully embraced by the artist himself during his lifetime, and he often fed them news and concert pre-sales even before the media. According to emails from founder Jarkko Arjatsalo, a Finnish fan who Cohen kept up a correspondence with for two decades, there were over 200 fans at the last Hydra gathering. They charter boats around the island, hike up the many hills, and screen concerts at the open-air cinema.

In 2014, while Cohen was still alive, the forum decided to do something for his eightieth birthday and settled on a bench on Hydra overlooking the sea. Cohen wrote, “I bow my head in gratitude” in a message to the group, but he never got to sit on it himself. The entire island of Hydra is a culturally protected monument and it’s not easy to build there. By the time they got permission from the Historical Office in Athens and found a local architect to build it, Cohen had passed away. It was inaugurated with a concert in 2017, a year after his death.

Walking the cliffside road from the inner town to the outer reaches of Kamini Beach, it’s easy to walk right by the recessed stone brick bench. Look carefully and you’ll see the plaque with a quote from Cohen “. . . came so far for beauty.” Somebody has tagged the wooden backrest with spray paint, which spoils some of that beauty he, and I, came so far for.

But when I look over the ocean and see the sun setting, its perfect orange reflected in the deep blue of the water Cohen used to swim in every day, I get it. The Greeks are very serious about their sunsets, and this is the best one I’ve seen. It’s vistas like these that drew him back to the island over and over and over again. Unlike the larger-than-life mural of Cohen's face on a building on Montreal's Crescent Street, the specific bench is not the attraction—but it’s a good place to take in the island’s “orderly and sweet” charms.

*

Nowadays, Hydra still attracts artists from all over the world, but the tax bracket is a little higher. You can’t buy a house for $1500 anymore, nor can you live on honey and bread and salt-water swims without regular income. Airbnb has done very well on Hydra.

The DESTE Foundation, a Greek contemporary art organization, has taken over a historic slaughterhouse a short walk from the Cohen bench. Where it used to colour the ocean red with blood and guts, it now draws people in for major installations.

When I’m there, it’s showing an exhibition by ultra-profitable American artist Jeff Koons. Inside, a moving statue of the Greek god Apollo “plays” an incantation on an ancient stringed instrument that, as you move in closer, reveals itself to be “Champagne Supernova” by Oasis. Outside, a large sun-shaped wind spinner adds an Instagrammable embellishment to the gorgeous views.

In the time since I’ve returned from Hydra, the town has made a rare exception and made Koons’s Apollo Wind Spinner a permanent fixture. Koons is a controversial figure, but it’s hard to deny the eye-catching mix of ancient and modern landscape. It reminds me of “Bird On The Wire,” which Cohen wrote when hydro wires were brand new to the formerly electricity-free island. The island evolves with its inhabitants without losing its innate sense of being.

But despite being such a haven for high-profile artists both old and new, you’re more likely to find monuments to marine heroes on Hydra.

“When I first arrived, I was blown away by the density of the story on this small island,” says Josh Hickey, an American-born, Paris-based art curator who spends months at a time on Hydra. “You do some digging and you end up in this rabbit hole of amazing writers who’ve all stayed or written about the island. But everyone is pretty discreet about it.”

From September until October, Hickey runs the Hydra Book Club out of the Historical Archives Museum. Up the stairs past displays explaining the relatively recent 18th-century-beginning history of Hydra as a safe haven for those fleeing the Ottoman Empire, there’s a room filled with books. Tables are stacked with copies of Henry Miller, Lawrence Durrell, Gregory Corso, Charmian Clift and George Johnson, Allen Ginsberg, Alan Ansen, Jeanette Winterson, and Polly Samson, along with rare copies of Beautiful Losers and The Spice-Box of Earth. All of these foundational writers spent time in Hydra and penned words about its mountainous charms.

Yet, this is one of the few spots on Hydra where books are even sold. That’s compelled Hickey to make Hydra Book Club an annual exhibition, though he describes it as more of an art project than a commercial one. “I'm more interested in the social interaction that it provokes than the selling of an individual book,” he says. Sometimes, people that were part of the scene in Cohen’s day stop in and tell him stories. As much has been written, there are more stories whispered over mastika at tavernas. “It can be very gossipy,” he says. “Which is funny, because that’s what it was like in the ‘60s.”

There’s a fine line between celebrating the art scene and parading it, because the rustic serenity of Hydra is what has historically made it such a haven. Having a drink and engaging in the boisterous conversation at the port can make it feel like a community, but take a few steps up the mountain and the air is so silent that your own footsteps sound thunderous. Lounge on one of the concrete bathing platforms and you feel part of a landscape that is indifferent to your ego. It feels immortal. But when one figure looms so large over a place, it’s possible to cast such a shadow that it’s hard to see what was originally there. After Cohen wrote the wistful “So Long, Marianne” looking back at his tumultuous but loving years with Ihlen on Hydra, he later joked onstage that when Ihlen first heard the song, she asked him who it was about. “It can’t be about me, because my name is Marianne-nah,” she said. She’s forever immortalized with the wrong name.

“Greece is a good place to look at the moon, isn’t it?” Cohen asks in his poem “Days of Kindness.” He’s right, on Hydra the moon is as bright as any place I’ve ever seen it. But as I think about that poem, I can’t help but wonder, am I seeing it through my eyes or through his?

*

When I finally find Leonard Cohen’s house, it’s by accident. I’ve been wandering aimlessly uphill through the winding streets, following the sounds of horses and chickens past long-abandoned churches with for-sale signs. Every time I turn back towards the port, I see a new brilliant angle of the island stage.

Turning onto what seems like a narrow side alley, I see a couple in shirts with logos from the Montreal marathon. They’re snapping pictures of a blue and white street sign. I lean closer and see what it says, in Greek and English script: Leonard Cohen Street. Then, I see the pleasant but unassuming bougainvillea-adorned white house. That’s the one!

But, as I share the discovery with my fellow Canadian Cohenites, our voices never go above a whisper. This feels strange, we agree. We’re all Leonard Cohen fans, but there could be someone in there. It feels like we’re sneaking around. So we decide to continue our conversation elsewhere. We turn onto the next street and head down towards the port together.