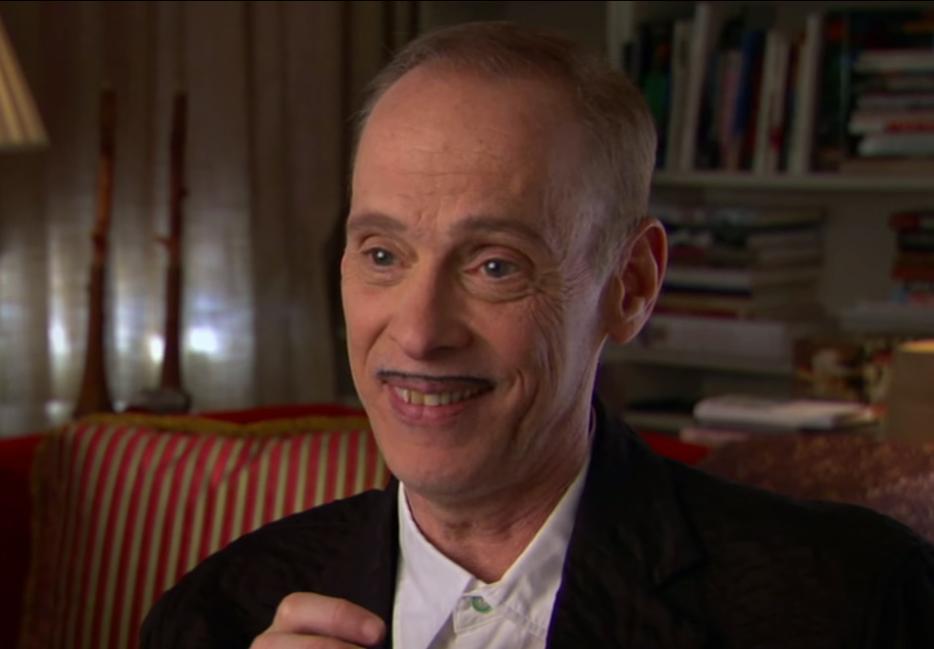

John Waters adopted his pencil-thin moustache in the 1970s as an ironic nod to Little Richard, but quickly discovered that “it’s tough for a white man who isn’t that hairy to grow one.” To supplement his meager facial hair, he coloured the top of his lip with a Maybelline eyeliner pencil. Today, he carries pencils in his pocket, his car, and in each of homes. Once, while recovering from a concussion, he made a panicked call to his mother, asking her to deliver an emergency pencil to the hospital. “We had so many issues at the time, the moustache had to get in line,” he wrote in his 2010 book, Role Models.

The moustache is a key player in Carsick: John Waters Hitchhikes Across America, his new book about the cross-country journey he took in 2012. Standing for hours at the side of Interstate 70, and retiring to cheap motels at night, he struggles to keep his little whisk of facial hair from getting bushy, or being drowned out by stubble. In a fantasy chapter, he imagines desperately dabbing it with cigarette ash, as if he’d be naked without it.

If anyone else spent as much time contemplating his own moustache, it would come across as hopelessly dull, but part of Waters’ fascination is how he deliberately curates his own eccentricity. Even in Missouri, Utah, Colorado, and other states that aren’t bastions of Waters fandom, he is aggressively eager to inform drivers that he is not homeless, but, in fact, the creator of Hairspray. The upper-lip insignia is proof that he is really John Waters.

The notorious final scene of Pink Flamingos, his breakthrough effort, is not so much about Divine eating dog shit as the idea that a real filmmaker filmed a real drag queen eating real dog shit, and that we’re all really watching it. As Waters has said, no one could watch that scene without telling their friends.

In Carsick, Waters admits that his return to writing books was motivated in part by his inability to secure film financing. After the simultaneous collapse of the global economy and mid-level independent filmmaking in 2008, he struggled to raise the $5 million needed to make his “terribly wonderful children’s Christmas adventure,” Fruitcake. Nowadays, he keeps active as an author, talk show guest, documentary talking head, public speaker, award show presenter, and conceptual artist (his multimedia pieces are collected in three monographs, Director’s Cut, Change of Life, and Unwatchable). In other words, his films are only one component of the ongoing, multidisciplinary performance art piece that is John Waters. He half-jokes that he has found a more lucrative career as a full-time “John Waters impersonator.”

Robert Altman once described his own filmography as one long film, divided into chapters. This idea is especially applicable to Waters, whose obsessions (celebrity criminals, bizarre sexual fetishes, the underbelly of suburbia) carry from film to film, and whose clunky aesthetic remained consistent even when he graduated to Hollywood. Waters’ characters typically serve as his mouthpieces. Deep into his career, the likes of Tracey Ullman and Kathleen Turner still talked in the same hyperbolic Waters-speak that Divine and Edith Massey parroted at the outset (“I hate contemporary photography!” yells Christina Ricci at an emotional moment in Pecker, with delivery similar to Divine’s immortal, “Oh my god, someone has sent me a bowel movement!”). How much you enjoy a dodgy late-period effort like A Dirty Shame—with its many scenes of characters awkwardly defining their sexual fetishes—will likely depend on how much you enjoy hearing Waters’ voice.

The notorious final scene of Pink Flamingos, his breakthrough effort, is not so much about Divine eating dog shit as the idea that a real filmmaker filmed a real drag queen eating real dog shit, and that we’re all really watching it. (The fourth wall-breaking narration: “Watch as Divine proves that not only is she the filthiest person in the world, she’s also the filthiest actress in the world!”) As Waters has said, no one could watch that scene without telling their friends.

Lines recognizable from his ubiquitous talk show appearances (“We should make heterosexual divorce illegal”) now come from his fictional travelling companions, carrying on the tradition of John Waters characters who talk like John Waters. There are so many references to his earlier films and books (“‘You want another whipping?’ he shouts like a madman, just like Dawn Davenport in Female Trouble) that curious readers should prime themselves on his film work, and be sure to watch the extras.

Waters built his legend on moments like these. And the appeal of his movies now has less to do with their content as where they fit in his outrageous mythology: from teenage n’er-do-well to alt-cinema legend. His later work sometimes requires deep immersion in Watersworld to even make sense. At the end of Cecil B. Demented, Cecil (Stephen Dorff)—a cinephile terrorist who kidnaps a starlet, Honey Whitlock (Melanie Griffith), for his underground movie—directs Honey to light her hair on fire. The gag just sort of dies onscreen, but its interest is that Waters reportedly gave the same direction to Mink Stole for Pink Flamingos (she declined).

Other examples: In A Dirty Shame, a character says, “I’m not a prude—I’m married to an Italian”—a funny-enough line, but funnier when Waters explains in the DVD commentary that it came from Mary Avara, former member of the Maryland Board of Censors. A subplot in Pecker involves the uproar in Baltimore over a strip club that shows pubic hair. As a comic notion, this is about 30 years past its sell-by date, but in the commentary, Waters goes into the long and tortured history of public pubic hair in Baltimore. He laughs that his close friends are always spotting his obsessions in his movies; unless you’re his friend, Waters’ DVD commentaries are a necessary extension of the text. They’re sometimes funnier than anything in the film.

Waters claims that the hero of Cecil B. Demented is self-parody. I don’t really buy that, since Waters has always been a cannier businessman than Cecil. Unlike Cecil, he has been able to adapt his sensibility for mainstream consumption (most successfully with Hairspray, which has become an industry). In Carsick he writes that, with a full-time staff and homes in three cities, he’s not interested in returning to his low-budget roots. And he is not beholden to cinema. In years between movies, Waters has made a comfortable living on the road, as a behind-the-scenes storyteller and pontificator on a stable of pet topics now very familiar to his fans.

*

The first two thirds of Carsick comprise a pair of “novellas” describing hypothetical hitchhiking trips—“The Best That Could Happen” and “The Worst That Could Happen”—in which Waters essentially makes himself the star of two John Waters movies. In the first, he hooks up with a group of friendly carnies, the singer Connie Francis, some obsessive paperback collectors, a few working-class studs, and aliens who give him a “magic asshole.” In the second, he encounters aggressive fans, homophobic cops, a serial murderer of cult film directors, and a pair of drag queens who impersonate killers that Waters made light of in an earlier book. The stories read like prose versions of the movies Waters can no longer secure financing for.

Lines recognizable from his ubiquitous talk show appearances (“We should make heterosexual divorce illegal”) now come from his fictional travelling companions, carrying on the tradition of John Waters characters who talk like John Waters. There are so many references to his earlier films and books (“‘You want another whipping?’ he shouts like a madman, just like Dawn Davenport in Female Trouble) that curious readers should prime themselves on his film work, and be sure to watch the extras. For Waters fans, the book offers something out of the ordinary, but you have to keep reading to get there.

Even though Waters regularly mines his life and career for fodder, he has always seemed a little guarded. For someone who delights in bizarre sexual practices, he was noticeably cagey about his own sex life in his earlier books, Shock Value and Crackpot, aside from brief acknowledgments of his sexuality. In Role Models, he opened up about his taste for “blue-collar closet queens” in the chapter about pornographer Bobby Garcia. In Carsick he goes further, casting himself in several explicit fictional sexual encounters.

As a full-time “John Waters impersonator,” Waters runs the risk of letting his persona ossify. ... The character Waters has created for himself is arch and witty, which makes it seem churlish to complain. But given how familiar that character has become, I find it more satisfying to see him let his guard down.

The book’s final third has less sex, but is more revealing. “The Real Thing” documents his actual trip, through lands where his celebrity is less pronounced. About half the drivers who pick him up recognize him, although sometimes from his cameo in Seed of Chucky or Lonely Island’s “The Creep” video. Others are Good Samaritans who nod politely at his claims of being a famous film director and still offer him money. When the band Here We Go Magic picks him up and tweets his photo, the story goes viral, but he still has to spend hours waiting at the side of interstate highways.

As a full-time “John Waters impersonator,” Waters runs the risk of letting his persona ossify. One reason I prefer the last third of Carsick is because circumstances force him to put that persona aside. The most affecting sections involve “The Corvette Kid,” a 24-year-old Republican councilman who picks him up in Maryland. Despite their differences, the two form a delicate friendship, and end up traveling far past the Kid’s destination. The Kid later plays hooky to pick him up again in Colorado, much to his mother’s dismay, and plans to join him again in San Francisco. Waters describes their friendship as a “bromance,” but the Kid’s friends and colleagues start wondering why a Tea Party Republican is on a road trip with a gay filmmaker. When the Kid puts a “Do Not Disturb” sign on his motel door, Waters’ first instinct is to hope he isn’t with a girl, then he asks himself why he feels that way. He doesn’t answer the question, and lets much of their bond go unspoken.

When I think of Waters’ career, it seems more a trajectory of branding (from the underground to Hollywood, from enfant terrible to elder statesman) than artistic growth. There is such consistency to his work that after Carsick’s aggressively Watersian early chapters, the Corvette Kid sections have a melancholy, quietly emotional quality that I frankly didn’t know he was capable of. The character Waters has created for himself is arch and witty, which makes it seem churlish to complain. But given how familiar that character has become, I find it more satisfying to see him let his guard down.

It must be difficult for Waters to know how much to reveal when his livelihood depends on being a version of himself. But like the surprisingly moving chapter in Role Models about his friendship with former Manson girl Leslie Van Houten, Carsick gives just a tantalizing hint of the book John Waters might write if he didn’t need to be John Waters.