We lost something more than a writer when Farley Mowat died at 92 last week. We lost an entire Canada.

My first job in journalism was at Quill & Quire. Once, while preparing for some anniversary or other, I was reading through the archives when I made a startling discovery: before Robertson Davies, when it came to CanLit, there wasn't much to talk about.

I'd corresponded with Davies in school, which I suddenly realized was the equivalent, in American Lit terms, of writing to Melville or Emerson or Hawthorne. Morley Callaghan preceded Davies, and of course there's Susanna Moodie and any number of others, but the notion of CanLit—a charming neologism I don't hear much anymore—more or less began with Davies, whose first novel, Tempest-Tost, came out in 1951. Davies' Canada was a small-town Canada, with roots in Hardy and Dickens, and the man himself was a literary character writ large. He was a novelist we could be consistently proud of, decade after decade, on the world stage. He was writing with the big boys, and giving us back a Canada that made us think we weren't that different from the US or the UK.

People of the Deer, Mowat's first, came out a year later, in 1952, and gave us a Canada that was not Davies’, not his readers', not aspirational or even glamorous. He gave us the Canada that actually was, the one we so often turned away from reflexively, distancing ourselves from it in public like a loud aunt or a cousin who doesn't shower enough. It was a Canada of wilderness, of aboriginal people, of animals and space and survival and death, cold and wet. It forced us to face our excessive geography, of which we were simultaneously proud—second-biggest country in the world behind the Soviet Union—and ashamed. We were bigger than the US, sure, but come on: they contained multitudes, a town every half hour, and enough history and myth to play in the big leagues with nations and peoples centuries and millennia older. Anyone who'd ever driven through the Prairies knew Canada didn't have any of that.

He gave us the Canada that actually was, the one we so often turned away from reflexively, distancing ourselves from it in public like a loud aunt or a cousin who doesn't shower enough.

Mowat's Canada was unlike any other country, its crimes and its triumphs utterly unique. People of the Deer was debated in the House of Commons and denounced by then Minister of Northern Affairs Jean Lesage as a pack of lies, which is remarkable for three reasons: first, it wasn't non-fiction; second, it was all true; and third, the very birth of CanLit was being discussed, in medias res, during Question Period.

People of the Deer was about a people called the Ihalmiut, a Northern people, ancestors of the Inuit, who subsisted on caribou until they were relocated away from their source of food and meaning and, ultimately, out of existence. Lesage said there were no such people and never had been. But there were, and the fact that it took decades to establish this simple fact behind this anything-but-simple fiction is a testament to the national state of denial that bordered on cognitive dissonance that existed at the time.

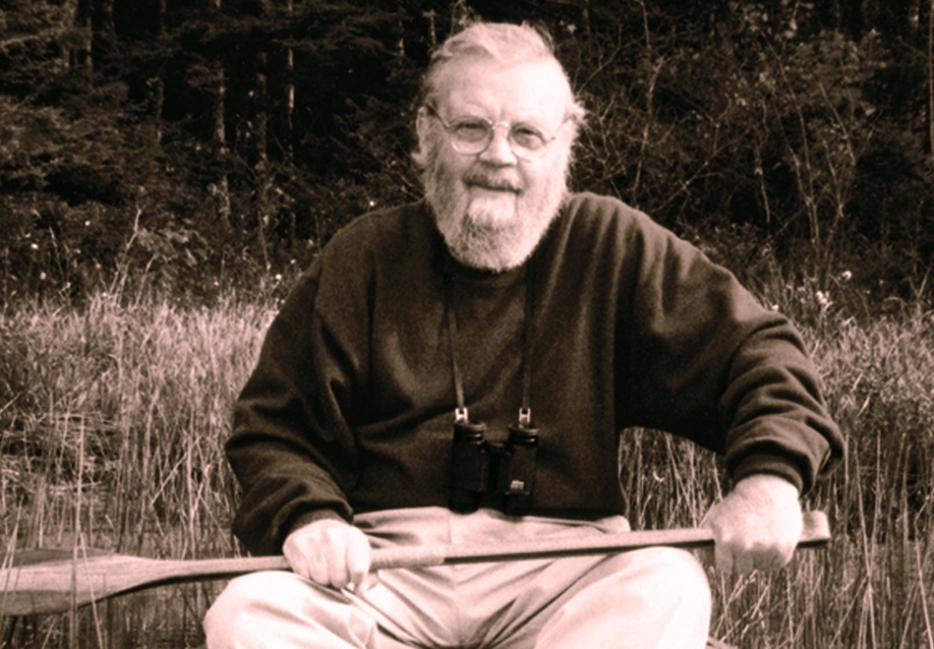

But People of the Deer sold. People read it. And Mowat wrote on—more books, epic tales in Maclean's and elsewhere. He talked on the CBC, and to anyone who would listen. He looked like a mountain man, sounded like your rude brother-in-law from the sticks, but the Canada he conjured was both exciting and strange yet somehow familiar, a Canada we always knew but had been loath to acknowledge for fear of making those American igloo jokes seem too real.

Soon, Northrop Frye backed Mowat up with his concept of Canada's garrison mentality. Frye's student at Victoria College, Margaret Atwood, upped the stakes with Survival, the book that made me think she should stop writing fiction and devote her huge brain solely to more books just like this. Over the course of the ’60s and ’70s, with an assist from Expo 67, Canada was getting ahold of itself. It wasn't England, and it wasn't the US, and that was OK. We were something new on this earth, something spectacular, a young nation with ancient cultures in abundance.

He looked like a mountain man, sounded like your rude brother-in-law from the sticks, but the Canada he conjured was both exciting and strange yet somehow familiar, a Canada we always knew but had been loath to acknowledge for fear of making those American igloo jokes seem too real.

I don't know what happened—I'm sure Atwood does—but sometime around 1990, things changed. If you wanted to pick a single turning point, you could do worse than the 1992 Booker Prize, which heaved Michael Ondaatje into the stratosphere, a rise bolstered five years later by a couple of Oscars and an episode of Seinfeld. Suddenly, Mowat was demoted to CanLit's silver age, because this was clearly the golden one dawning, defined by the new-new Canada, a Canada of immigrants. We were so proud to be proud of Sri Lankan Canadians and Indian Canadians and Caribbean Canadians, so keen to be seen as the cosmopolitan nation we aspired to be. This immigrant literature was, by definition, an urban literature, and we were a little proud of that, too, though more quietly so. Canadians lived in cities, and our cities bore stories, like London and New York. Sure, maybe Mistry was writing about Mumbai, but he was writing from Toronto.

Rudy Wiebe, one of Mowat's natural successors, was writing all through this period, but has been less prolific since the 1980s. There were aboriginal writers, the sort to whom Mowat and Wiebe should have been the gateways, but they didn't stick. Tomson Highway and Drew Hayden Taylor stayed in the small presses. Thomas King made it out, but has seen his greatest successes only recently. There may be an Inuit novelist, but I'm afraid I don't know her.

Mowat did inspire real change. I can't imagine Katimavik, founded in 1977, would have happened without him. And the attention he drew to the North threw the baton to the Inuit who became the founding mothers and fathers of Nunavut, the result of the world's most remarkable land treaty. Frobisher Bay became Iqaluit, Eskimo Point became Arviat, and a century-long struggle between the Inuit and the South found the beginnings of resolution.

But Southerners still don't go up north. There are maybe two aboriginal restaurants in the country, and maybe two or three hotels that celebrate the cultures. We still see the Prairies and the tundra as empty, still see British Columbia mostly as stops along the Lower Mainland, still call a huge chunk of the north the Barrenlands.

Canadians lived in cities, and our cities bore stories, like London and New York. Sure, maybe Mistry was writing about Mumbai, but he was writing from Toronto.

Back in 1966, when Mowat took a comprehensive tour of the North for Maclean's and McClelland and Stewart, he made note of a slip of paper his travelling companion passed him as they looked out the window of the noisy Otter in which they were flying over the east coast of Hudson Bay. “Only Europeans would have called this the Barrenlands,” the note said. “Shows you how blind we've been. And are.”

Mowat didn't fail—we failed him. He quoted that note as late as 2002, in High Latitudes (now unforgivably out of print, it seems), which he wrote to give further voice to the Inuit he interviewed on that 1966 trip. Mowat's last public statement, on the May 1 edition of The Current, was a blast against installing WiFi in our national parks (“I think it is a disastrous, quite stupid, idiotic concept, and should be eliminated immediately”). He never lost it, that love for the wilderness as wilderness rather than attraction, the taming of which he equated with the taming of our very soul, and the subjugation, the effacement, of the people who have lived with it and within it for millennia.

It was us. We got distracted, took our eyes off the prize. Atwood's still around, and so is Wiebe. And Ken McGoogan, though far more polite than Farley, has been writing the wilderness as fast as he can. A nation is nothing but people and stories. Let's turn around and face ours, find his Canada, make it ours again, and thank Farley for it.