I was 14. The Berlin Wall was a dam that had broken three years before, and was well on its way to becoming eBay merchandise. The Western world was steadily flooding the Eastern world with all kinds of garbage: McDonald’s, New Kids on the Block, Vidal Sassoon conditioner samples. And we gobbled it all up, even the unsanctioned Mars bars. But besides garbage there were a few gifts: Ives Rocher cosmetics, shiny lycra leggings, and angry music that wasn’t Metallica (which was the music of older kids)—specifically, Nirvana. The name seemed profound and epitomized the opposite of what life was then like in Poland.

For me the band arrived with a sudden roar one day while sitting in the back of physics class, or maybe it was chemistry. (I sat in the back of the classroom with the few other students who didn’t listen to New Kids.) At 14 I needed music for more than just my ears; I was like every other Holden Caulfield, it was obvious to me that everything—parents, society—was basically phony. My friend R. handed me a cassette with the cover showing a naked baby swimming underwater, chasing after a dollar bill. Normally R. listened to Metallica and Iron Maiden, which wasn’t my thing, but at least that made him seem more aware of all the bullshit (parents, society) than most of my peers. So I trusted him and said I’d give it a listen. It was 1992 and in a few months I’d be leaving to move to North America.

A friend was coming over that afternoon of the cassette, but when I heard her knocking on our door I didn’t open it—I needed to be alone with this new music. My hiding like this had happened once before, when I got Sinead O’Connor’s The Lion and the Cobra. But unlike Sinead O’Connor, Nirvana seemed something else besides just capital-A Angry. It wasn’t the lyrical content that appealed to me—hey, I couldn’t understand English at the time—but something in the sound that reflected the sense of disillusion I felt in this wounded country now embarrassingly throwing itself at shiny garbage.

I needed to talk about what I had heard so I went on a date with R. even though I didn’t like him that way. We talked about our isolation in the land of silly music and shiny shit, and about our personal Angry. R.’s father was beating him for not being an A student. I was mad about my impending immigration. We both hated McDonald’s. But it wasn’t just anger, there was resignation: to the bad dad, the immigration, the McDonald’s, and everything else. Nirvana was the perfect soundtrack to it all, just as it was the perfect soundtrack for many Angry teenagers outside of Poland who were also resigned to their circumstances. This I quickly learned upon arriving in a small Canadian town that was once summed up by one of its residents thusly: “Welcome to Woodstock. If the trains won’t kill you, the drugs will.”

I went back to Poland every summer after we emigrated to visit. The second summer was after Kurt Cobain had shot himself. I was 17 and had never been in love. In Poland my best friend had moved on from New Kids and like everyone else was now wearing horrible flannel shirts, though usually as a skirt around the waist. The two of us took the train to a seaside town where flannel-shirted teenagers drank all day like vagrants, hanging around the fountain in the central square. We were city kids pretending to be in more trouble than we were. At night we camped illegally on a family campground in our dinky little tent. We would sometimes move the tent in the middle of the night to evade the camp authorities. Then one afternoon a beautiful boy came up to me on the street and asked, “Where were you when you found out that Kurt Cobain died?”

By then I liked Nirvana okay and that’s about it. But I had a flannel shirt. And I did remember where I was when Kurt Cobain died: I was in Woodstock, in Canada, sulking in my room as always, annoyed by the jolly April sun. A friend called me. She sounded strangely triumphant as she told me the news. She still listened to Vanilla Ice and she wasn’t really a friend; we hated each other’s guts.

“Good,” the boy, O., said. He said he had noticed me around town. He said that he had been shooting hoops on some decrepit basketball court when a friend ran up screaming that Kurt Cobain was dead. They abandoned the court and ran to a local bar to get shitfaced.

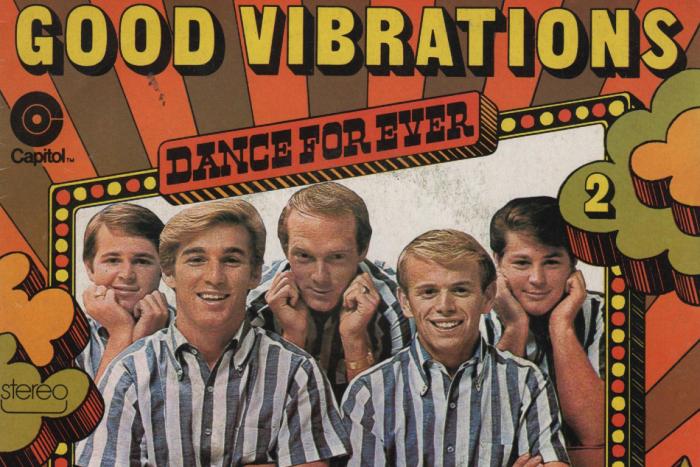

This was O.’s JFK assassination moment. Not everyone’s. A lot of teenagers in Poland were excited by all the post-communist developments then, five years after the wall had fallen. In big cities like Warsaw, there seemed to be more opportunities for work. Everyone was buying and selling things; there was a huge, ugly market sprawling right beneath the Palace of Culture (gifted to us by our former friends from USSR in 1952), stalls loaded with Adidas, Doc Marten and assorted other knock-offs, and boom boxes loudly pumping bouncy dance music.

But in blue-collar towns like where O. came from nothing had really changed—or it had changed but for the worse. The basketball courts were still crumbling. Children spent their days loitering about town and trying to avoid the abuse of their frustrated, newly unemployed parents (employment was always there during the red regime). Older children, the teenagers, smoked and drank in bars in the afternoon and listened to the music of their disillusionment. These towns were the real grunge.

The Kurt Cobain question turned out to be O.’s pick-up line, a test to see if we had anything in common. It actually didn’t matter if we had things in common—being hot was enough, he said later. We looked like spoiled Warsaw girls, he said. When he asked the Cobain question he expected the Warsaw girls wouldn’t have an answer, wouldn’t have paid attention to where we were when we heard Kurt Cobain had died, wouldn’t have cared. My answer impressed him and I felt proud that I’d passed some angry boy’s test. And he was hot and I was shallow, too. I fell in love for the first time; him too.

Later, O. and two of his friends visited me in Warsaw, before I flew back to Canada. During the day I showed them all the “historical” (post-World War II reproductions) palaces and other touristy things. At night we went to the grungiest club in town, Hybrydy, where downstairs they played hard music like Rage Against The Machine and Nirvana. It was scary and dark in that basement, black lights and cigarette smoke everywhere, and dumb, drunk teenagers throwing themselves into mosh pits. Someone handed us fluorescent markers and the boys took off their shirts. We wrote clever words like “Fuck” on their bodies. In the black light of the club the words shone like lasers.

At one point “Smells Like Teen Spirit” came on; I was pressed against a dirty brick wall by my “Fuck”-covered Romeo and I thought that this was going to be a moment I would remember for the rest of my life. My little nostalgia for the present. We were in love. But mostly we were desperate: I was leaving soon, and Nirvana was already in our past. I’ve hardly ever listened to Nirvana since. For me it turned out to nothing more than a soundtrack to burgeoning teenage hormones and a country trying not to fall apart.