In the essay “My Night of Ecstasy with the J. Geils Band” towards the end of Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, Lester Bangs writes about a time said band invited him onstage to collaborate with them. Rather than pick up a stray guitar or wail into an extra mic, though, Bangs performed on his instrument of choice: the typewriter. Bangs’s telling is breathtaking—the band carries on with their instruments while he conjures up a frenzied clattering with fingers slamming into keys—but in a more cynical moment, trying to pull apart the sonic components of that scene, one can also imagine a torrential racket, the sort of concept that, despite sounding wonderful on paper, enters ears almost irredeemably flawed.

Such is the sort of risk you run when pop and literature blend: the art forms can complement one another well, but beyond simple mismatched dissonance, there’s also the danger of a song, say, simply restating a story or novel’s plot. (Or, on the flipside, a writer’s fictional pop music coming off as entirely unconvincing.) Some of these collisions of music and literature make impact and leave little trace; others sear and reshape the landscape, affecting all involved parties, coming as they may through a lyrical mention, a nod in the liner notes, or even a particularly well-chosen sample.

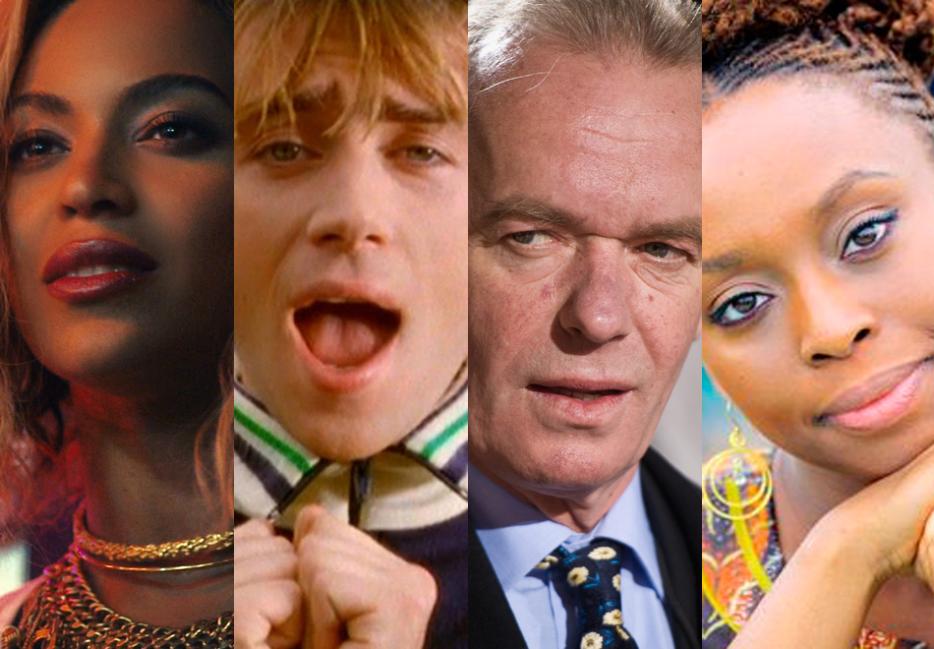

Beyoncé Knowles’s 2013 album Beyoncé greeted listeners with an amassed array of star power, including one from the world of letters: the acclaimed novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, whose recent Americanah landed on the fiction longlist for the National Book Award, and whose earlier Half of a Yellow Sun was a National Book Critics Circle Finalist. “***Flawless,” Beyoncé’s eleventh track, incorporates a lengthy sample of Adichie—taken not from one of her novels, but instead from a TEDx talk she gave about feminism. The appearance was covered by pop and literary journalists alike with abundant glee: book critics who’d championed Adichie’s work were pleased to see her words invoked by a pre-eminent pop star, and Adichie’s appearance gave numerous music critics a new angle from which to view the album.

When literature finds root in song (or songs), how does that affect both? Probably, it depends on the listener. As someone who was paying attention when reading Cobain’s praise for Süskind, I remember being delighted to find a copy of Perfume while shopping for books one day, and quickly picked it up. And I can remember a circa-2000 conversation in which friends, talking up the work of Martin Amis, cited Parklife’s influences as another reason to seek out his novels—kind of an, “If you like A, you’ll find that B shares its aesthetic” situation. These are the kinds of unexpected connections the overlap between music and literature can make, drawing readers to works they might not have otherwise encountered; two decades after its release, after all, Nirvana fans are still discussing Perfume, and much has been written about Rush’s nods, for better or worse, to Ayn Rand in their mid-1970s work. Sure, maybe those fanbases would have eventually intersected, but at their best, these songs and albums can take a pop artist’s enthusiasm for a writer and turn it on an unexpected, unsuspecting audience. It’s a broadcast as potent as anything.