A few weeks ago I wrote a poem that cost $2000. It’s about plastic lawn flamingos, and I wrote it at a lord-of-the-manor desk with knobbly carvings gleaming darkly on its upper thighs. Behind me, a wingback armchair and a thinky sort of sofa stood by in front of a big-ideas fireplace. On the mantelpiece were wooden honour rolls signed by previous occupants of my studio: Susan Orlean, Jeffrey Eugenides, and Wendy Wasserstein, to name-drop a few. I also captained a four-poster bed with snowy linens, lashings of flowered wallpaper, and, from my writing desk, a meadow with gamboling deer—at least one at any given moment, with a seasonal high of six. Deer, like everything else at MacDowell, operate in an economy of abundance.

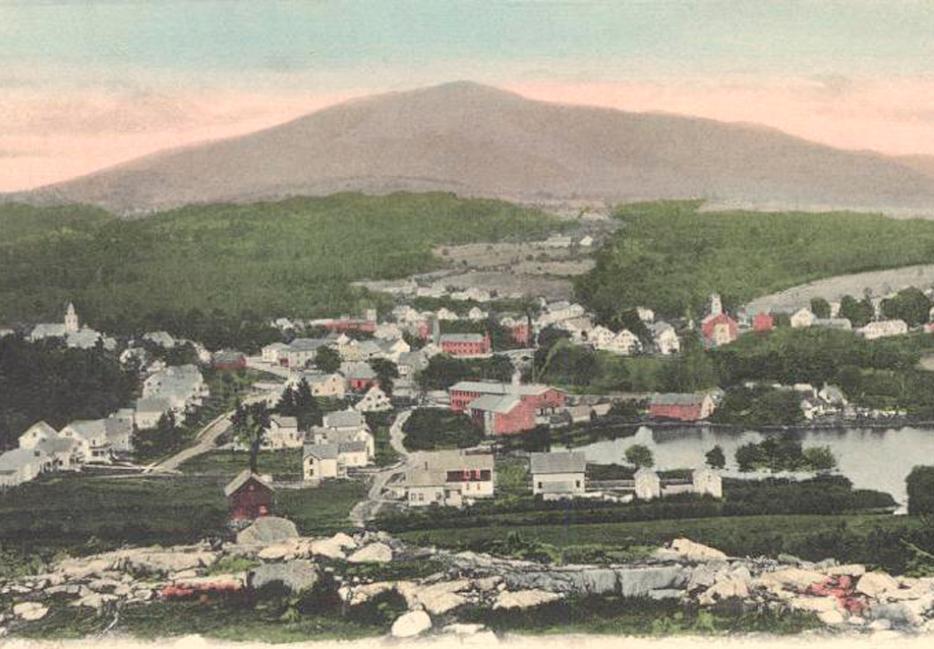

The MacDowell Colony is an artist residency in Peterborough, New Hampshire, and it has been running (with occasional interruptions due to hurricanes and/or penury) since 1907. MacDowell is free to artists, known to the administration as “Fellows” and to each other as “Colonists.” There are about 30 Colonists there at any given time, and everyone gets his or her own studio space and three meals a day. The residency was started by Marian MacDowell; she considered her husband, Edward, a classical composer of genius, and the Colony is now run by a sort of institutionalized fleet of literary wives, except most of them are burly men. Here’s Vera Nabokov with a new stack of firewood he’s chopped for you, and here’s Sophia Tolstoy tiptoeing up to your studio door with your lunch in a wicker picnic basket—he’ll leave it outside so as not to disturb you. Anna Dostoevsky knocked on my door one day hoping to put on the storm windows, but when he saw I was holding a pen and still in my pajamas he offered to come back later, and said, in all sincerity, “We can make our world revolve around you.”

Breakfast is hot between 7:30 and 8:30, and runs to lemon pancakes with blueberry compote, huevos rancheros, poached eggs, and the like. It’s dished up in Colony Hall, the converted barn that now serves as MacDowell’s central building, and while I didn’t make it to breakfast every day, when I did there was always bacon and almost always cake. Eating chocolate cake at breakfast seems indulgent at first, but it swiftly becomes an integral part of the creative process. Dinner is steak and strawberry shortcake, chicken with horseradish mashed potatoes and berry cheesecake, salmon with pesto vegetables and pumpkin pie, mushroom risotto and apple pie, shrimp jambalaya and chai pudding, tilapia on creamy polenta and bananas Foster. I had never even heard of bananas Foster, but now I can’t stop thinking about it.

Every artist needs to make his or her peace with money. Mostly what you need to make peace with is not having money, or having money because you also do something else the market values more.

During my six weeks at MacDowell, one number danced like a vision of unmerited sugarplums in my head: 400 dollars a day. I first heard this figure on Blake’s Famous, Magical, MacDowell TOUR!, the reminder for which was hand-delivered to my studio in the bottom of my daily picnic basket lunch. Blake is Blake Tewksbury, the kindest man ever to sport a many-pocketed vest and Tilly hat. Over the course of the three-hour tour, he drove a minivan packed with two novelists, a playwright, a poet, a composer, and two visual artists over the leafy lanes of the whole 450-acre estate.

Each of the 47 buildings has a story: here is Heyward Studio, named for former Colonists Dorothy and Dubose Heyward, who wrote Porgy and Bess. Here is MacDowell Studio, otherwise known as the Pulitzer studio: Michael Chabon (now chair of MacDowell’s board) wrote The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay here, and Aaron Copland composed Appalachian Spring. “No pressure,” someone in the van remarks, and we all titter uncomfortably. There have, in fact, been 68 Pulitzer Prize-winners at the Colony. James Baldwin came here, as did Leonard Bernstein, Meredith Monk, and Marcel Duchamp. It’s where Thornton Wilder worked on Our Town, Willa Cather worked on Death Comes for the Archbishop, and Jonathan Franzen worked on The Corrections.

This is both the promise and the threat of MacDowell, that here you can play pool badly on the same table where Alice Walker played it well. When the minivan passes a studio assigned to someone on the tour, Blake never fails to mention the “famous painter/writer/composer” who currently works there, and we titter uncomfortably some more. He’s half-kidding, but only half: MacDowell’s administration is realistic in its expectations, and the administration knows that not all its Fellows will produce a major masterpiece. At the same time, they’re hoping that at least one of us will, and we’re all hoping to be the one. The cost, Blake mentions off-hand, is $400 to host each of us per day.

Once Blake drops us off back at the Hall, a young novelist says, “I have to stop plucking my eyebrows!” “Why?” I ask. “Because I’m costing them 400 dollars a day!” she says, nervously twisting a button on her coat. “It’s taking up too much time!”

*

Every artist needs to make his or her peace with money. Mostly what you need to make peace with is not having money, or having money because you also do something else the market values more. “So do you teach?” is the first question of the day-job conversation at MacDowell. Many do teach, but not all: the novelist with the well groomed eyebrows had quit a job in fashion to come to the Colony; an installation artist stayed up late in the Hall doing bookkeeping for her dad’s construction company; a filmmaker was working as a fact-checker and agonizing over whether to accept her magazine’s offer of a full-time position, which would give her more job security but less freedom to work on her documentary. One memoirist was a clinical psychologist, another was a professional fundraiser.

So it’s rather shocking when, as an artist, people do value what you do. Money will occasionally be allocated to you in a way that doesn’t reflect ordinary market forces, and you will find yourself eating dessert three times a day while someone else washes your bedclothes. While at MacDowell, I often found myself thinking of David Foster Wallace’s famous essay on cruise ships, and in particular his description of what walking feels like on board an ocean-going vessel so large you can hardly tell you’re at sea: “7NC Megaships don't yaw or throw you around or send bowls of soup sliding across tables. Only a certain slight unreality to your footing lets you know you're not on land...walking feels a little dreamy.” The dreamy unreality at MacDowell comes of wading through slippery piles of other people’s money.

The 400-dollar-a-day figure does not reflect the cost of your personal shrimp jambalaya consumption; it’s a straight-up division of the Colony's total budget of $3.3 million by its number of days per artist per year. The Colony has an office in New York as well as on site in New Hampshire, and it employs 34 people, which, as the novelist of the now formerly well groomed eyebrows pointed out, means that the ratio of staff to artists at any given time is about 1 to 1. (“So when you’re in your studio working,” she said, “just picture someone else sitting right there beside you all day.”)

When I mentioned that in Canada, almost every writer I know has received federal or provincial grants that have supported them at the emerging stage, allowing them to quit their crappy serving jobs for six months or a year to write their first books, I was met with blank stares—I got the impression that people had trouble even imagining it.

Only 1 percent of MacDowell’s budget generally comes from the federally funded National Endowment for the Arts. Over the decades, MacDowell has built up an endowment that generates about 45 percent of the Colony’s annual operating expenses. For the rest, it relies primarily on wealthy individual donors. As Vartan Gregorian, former Colony Chair, delicately remarks in an essay, “While our vibrant and remarkable democracy does spread its wings wide to uplift many segments of our society, the arts, unfortunately, do not receive a substantial amount of federal, state, or local support, and so we depend on the generosity of Americans and American organizations for sustenance.” MacDowell was the first artist residency in the U.S., and its model has been extensively copied by other arts organizations. There are hundreds of privately funded residencies in the States, some of which are free, and they play a major role in sustaining artists creating new work.

In Canada, artists have greater access to direct individual support, and there are comparatively few residencies. The Banff Centre for the Arts, the closest thing to a Canadian counterpart to MacDowell, is a much larger institution—its budget is $57.5 million, and it employs 488 people—and it acts as a conference centre as well as an artist residency, while offering post-graduate level courses in dance, theatre, audio engineering and the like. Between federal and provincial grants, Banff receives 30 percent of its funding from the government. Because Banff is classified as a post-secondary institution, the funding it receives from the province of Alberta comes out of Alberta’s education budget, and this money funds the courses it offers as well as artist residencies. In addition, artists pay to attend residencies at Banff. I was there in 2007, doing my best to eat my weight in spare ribs and cheesecake to get my money’s worth. Unlike MacDowell, Banff is seen as a sort of finishing school for Canadian artists—in the same way that most writers I know have received government support, most writers I know have been to Banff.

Some dinner-table conversation at MacDowell revolved around books or paintings; often, though, it revolved around money. The American artists seemed to take a more entrepreneurial approach, in which every artist functions as a small business—individual artists in the U.S. chase funding opportunities the way arts organizations in Canada do, continuously identifying opportunities and writing grant applications. Colonists were constantly exchanging information about private foundations that offer grants, or pumping each other up before calling potential donors. Visual artists talked about money the most: if you are building a bronze disco ball so heavy you need a crane to lift it, or shipping a show across the country, you need funds. (Filmmakers talked about money too, mostly about how awful they feel constantly asking for it from the donors on their email lists.)

In Canada, unless you are running a more complicated project, the system is simple: there are creation grants offered to individual artists by the municipal, provincial, and federal government on a clear schedule with minimal requirements beyond the submission of a work sample. Once you have disseminated a minimum number of works (poems published, paintings exhibited), you are eligible for government support. In the years when I was writing my first book, for long stretches I worked part-time or not at all thanks to grants from the Conseil des arts et des lettres québécoises and the Canada Council for the Arts. When I mentioned that in Canada, almost every writer I know has received federal or provincial grants that have supported them at the emerging stage, allowing them to quit their crappy serving jobs for six months or a year to write their first books, I was met with blank stares—I got the impression that people had trouble even imagining it.

Where grants in Canada are common, government-issued, and often encourage emerging artists, grants in the U.S. are rare, primarily privately funded, and reward mid-career and established artists. When one of my friends gets a grant, it’s for 12 or 15 thousand dollars, and they maybe mention it to me in an email. When CA Conrad, one of the other poets at MacDowell during my stay there, won a Pew Fellowship in 2011, it was for 60 thousand dollars, and the Pew Foundation sent out a press release.

[pagebreak]

CA is an interesting American hybrid in that he wears a crystal around his neck and his ringtone is Tibetan monks chanting, but he’s pro-gun and gave me the recipe for something called Big Mac Soup—you tear a Big Mac into bite-sized pieces and then pour a can of Coke on it. (To be fair, this recipe is from his previous incarnation as a coke—the other coke—addict; now he boycotts Coca-Cola and is working on a vegan version of the recipe.) CA’s first book came out in 2006, although he had been writing and releasing chapbooks since the 1980s. He told me his conception of “real work” had been shaped by his upbringing in small-town Pennsylvania, where most of his family worked in—literally—a coffin factory. “My mother acts like I pulled off a bank robbery coming here,” he said. “She thinks it’s the stupidest thing in the world that they’re making me food for writing poems.”

CA is in his late 40s, and told me that he was happy to have arrived at a place in his life where he could accept the Pew and the fellowship at MacDowell without feeling too badly about it: “I think if I’d received this in my 20s I would have felt very guilty.” When he was 26, he said, a rich friend offered to take him to Japan. Her family fortune was in oil, however, and CA felt strongly that he shouldn’t accept a gift paid for with dirty money. He agonized about the decision, and he had a dream in which a Japanese woman told him to come to Japan to meet her because she had something to tell him. CA didn’t go, and while his friend travelled, he dreamed again of the Japanese woman, who told him he was very stubborn and that he was supposed to be there as she needed to talk to him.

This was in 1989. In 2012, CA told me, he had another dream. The woman was older, but he recognized her right away. “She said, You waited too long to come see me and now it’s too late, you have to wait for the next lifetime,” he told me, patting the bandana over his long hair. “So I was like, she was real! But she’s dead now, and I never met her.” The moral is, sometimes you should just take the money.

After briefly inhabiting a world where artists are royalty, it’s very hard to come back to reality. I’ve been back in the real world for two weeks, and I miss my studio. I miss my fireplace and my pale green walls with their fanciful wainscoting and my wax-papered cookies.

I found the MacDowell experience illustrative of a primary difference between Canadian and American approaches to money and the public good. The U.S. has a lot of bigger, better things built by philanthropists; there are more marble lions and free steaks, more classical white columns and bacon. People who show themselves to be among the most talented are rewarded more richly. One of the oft-quoted arguments against government arts funding is that the marketplace of ideas is like any marketplace: to survive, you should have to be among the best. Either you merit a lovingly prepared picnic basket lunch—rustically lined with checked blue-and-white gingham and packed with zucchini-risotto croquettes, mushroom bisque, a motherly packet of carrot and celery sticks, and a cookie wrapped in wax paper—or you don’t. Here, cake is the breakfast of champions. In Canada, there are few lavish public libraries built by philanthropists, and if you want cake you tend to have to pay for it yourself. But in the arts sector, as in health care and other social services, there’s more plain brown bread to go around.

It’s hard to know, but I think if I had had to wait until I was an established artist to receive any kind of support, I would have been weeded out a long time ago. I was a terrible, terrible waitress. When I got my first government grant, I was sharing an apartment in Montreal with another poet who also worked as a waitress; we were afraid of running up an exorbitant heating bill, so our apartment was always freezing—one morning, we literally had to break the ice on the cat’s water bowl. When the letter from the Quebec arts council came in the mail, I carried it around for hours before I could bring myself to open it, and when I did I cried. The sad part of this self-pitying story is that I’m a comparatively wealthy daughter of privilege: I’m middle-class, white, and already had a master’s degree. If I had asked my parents for money for the heat, they would have gladly given it to me. If I had had no safety net, the choice to pursue a career in the arts would have seemed even more unrealistic.

If I felt guilty at MacDowell, it may partly have been because I was getting the best of both worlds. The U.S. model means that when artists are rewarded, the rewards are marvelous. There are always rumours at MacDowell of the rogue Colonist who wouldn’t leave. In some stories it’s a woman: “She chained herself to the radiator,” someone will say. “She just couldn’t face going back to her real life.” Sometimes it’s a man: “He locked himself in his studio,” people whisper, “they had to break the door down and drag him out.” After briefly inhabiting a world where artists are royalty, it’s very hard to come back to reality. I’ve been back in the real world for two weeks, and I miss my studio. I miss my fireplace and my pale green walls with their fanciful wainscoting and my wax-papered cookies. I’ll definitely be reapplying as soon as I’m allowed to, which will be in two years. But in the meantime, I’ll be applying to the next Canada Council deadline, so that in the interim I can continue to work only part-time while I’m muddling toward my next book.

*

The private philanthropists who fund places like MacDowell and the government agencies that fund individual artists in Canada want the same thing: for artists to make their unique contribution to society. For MacDowell’s centennial in 2007, the administration put together a glossy book with a history of the institution and essays about the importance of supporting the arts. Artists, writes former Colony chair Vartan Gregorian, are the creators of humankind’s legacy. “We know that it is often the artists among us who save us from the great modern sin of indifference,” he writes. “[I]t’s artists who weave the past together with the future...who speak to our generation, surely, but who are also already calling out to our children, and our children’s children. It is our artists who bind the generations together in a great chain of life.”

In my six weeks at MacDowell, as different generations of artists came and went, I saw the rise and fall of three civilizations: the Mafia Civilization (dominated by a game where we pretended to murder each other), the Dance Party Civilization, and the Fart Joke Civilization. One night during the dance party era, I stood around outside a studio with a few other Colonists: another poet, a painter, a filmmaker, and the playwright Anne Washburn. Earlier in the evening, Anne had presented an excerpt from her show Mr. Burns: a Post-Electric Play, in which after the imminent apocalypse, a set of survivors sits huddled around a campfire helping each other to recall out loud, scene for scene, an episode of The Simpsons.

I told Anne it seemed to me her play was exactly what the post-apocalypse would be like. In the third act, she said, there was a whole musical version of The Simpsons’ “Cape Fear” episode, changed like a game of broken telephone so that Mr. Burns is the radioactive villain. “Some people think the ending is hopeful, and some think it’s despairing,” she said. “I’m not so sure it’s very hopeful, but I think people can do more with hope than with despair.” Music leaked through the open studio door, and inside I could see a printmaker from Michigan doing breakdance freezes and an experimental filmmaker from Florida jumping madly up and down.

Are we worth it? I don’t know. None of us really believes our work will be what lasts, that we’ll be the ones to bind the generations together in some great chain. If Anne is right, and what will really bind future generations together is fondly recalled episodes of The Simpsons, then both MacDowell and the Canadian government have been betting on the wrong horse—art that succeeds in the marketplace really is the best expression of our humanity. But maybe some broken-telephone, radioactive version of something we invented here—a plot, a shape, a sound—will help form the culture that succeeds this one. No one can predict the future value of a play, poem, or painting in progress. If investment isn’t a science, is it tautological to call arts investment an art?