In 2011’s The Great Northern Brotherhood of Canadian Cartoonists, the artist Seth toured an imaginary, fading guild by the same name, interpolating his own pastiches and inventions into national comics history. The most unusual fragment was The Great Machine, a 1970s experiment created by one Henry Pefferlaw. After buying a disused apartment building, its narrator and spectator hears mysterious noises behind a bricked-door down in the basement. “Beyond the door a stair descends … The roar and clatter of machines grows louder with each step down.”

Most of the book-within-a-book is simply first-person exploration of this unmappable and illogical labyrinth, filled with machinery, pipes and gauges and cogs and boilers and generators, some archaic, some modern, others strangely futuristic, all operated by an unseen power. And over one threshold, inside a chamber that extends for miles: “A pool of perfect black stillness … From some distance is heard the tolling of a great bell. The sound of which imparts a deep melancholia to the listener.” There is no conventional narrative, no dialogue, only bewildered description.

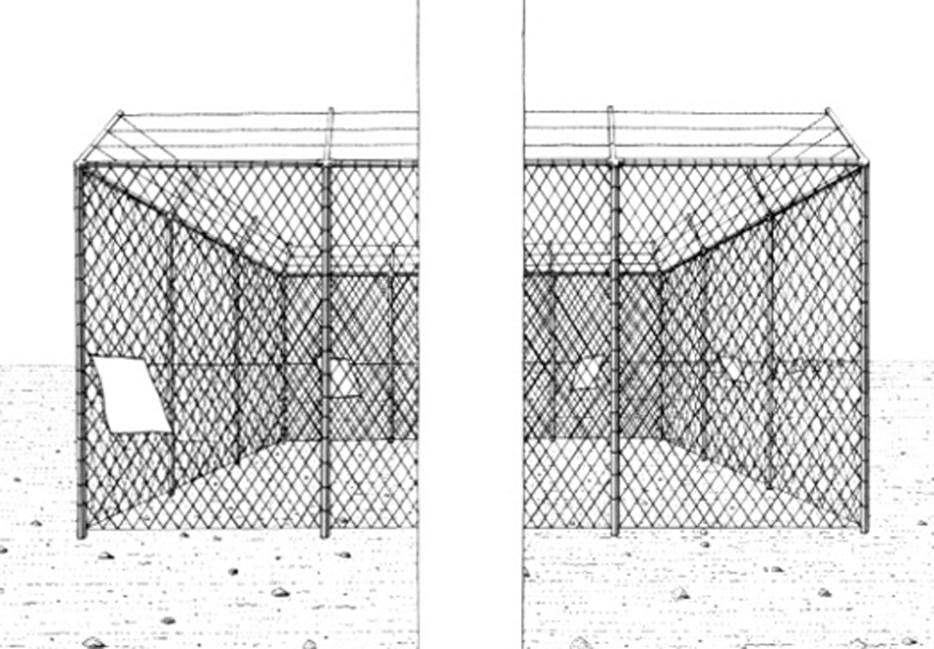

The Great Machine was based on the enigmatic comics of Martin Vaughn-James, an obvious connection that Seth humbly avoids mentioning during his introduction for the new Coach House reissue of Vaughn-James’ The Cage. Surveying the book’s desolate environments—ziggurats, a pumping station and, yes, that barbed-wire cage, each devoid of human figures—he asks questions without answers: “What is the cage? Why are we watching from within it? Is the viewer the prisoner in the cage? Locked inside the cage? Is it the cage of time? The cage of perception? Maybe the cage is reality itself?” You could add another: was The Cage, released in 1975, one of the earliest graphic novels?

Will Eisner’s 1978 collection of interlinked stories, A Contract with God, is routinely credited as the very first. Eisner didn’t even coin the term, though, only popularized it, along with the attendant confusion: Does “graphic novel” describe a form or a marketing category? Bookstores stock lots of memoirs under that section. Finding some creation story in cave paintings or ancient vellum is a pointless impossibility, anyway; Cervantes didn’t become a novelist until centuries after his death. What’s fascinating about the proto-graphic-novels that preceded A Contract with God is how their mutant idiosyncrasies intermittently passed down to today’s comics. There are myriad examples: the woodcut novels of Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward, Milt Gross’ He Done Her Wrong, Jules Feiffer’s Passionella, It Rhymes with Lust. And Martin Vaughn-James.

The last of three comics the Bristol-born Vaughn-James published with Toronto’s avant-garde Coach House Books during his relatively brief stay in Canada, The Cage was more reduction than culmination. As Seth notes, it eschewed much of the medium’s common language: no word balloons, no cartoon stylization, no more than a single panel per page. (None of Vaughn-James’ previous texts had a traditional plot, but there were recognizable living beings.) Tangled clothes, surveillance devices, a trail of black ichor and other ominous motifs rearrange themselves into various diagrammatic formations. Time curls in multiple directions. The Cage’s settings shudder with rot and then look new again after the turn of a page. Its narrator rambles observationally, like a tape reel skipping forwards and backwards: “…the plain…paved across its vast expanse with stones, sweeping like a cobbled sea beneath that line, that perfect horizontal drawn across the void…an arid, inorganic residue, stretching out toward a single, hard, remote and unassailable frontier…the sky…as white as paper…” Now and then the book might be describing itself: A tangle of truncated opaque screens repeating its convulsions. A complex network of forms arranged according to some logic separate and alien. A frozen geometry of mutilated props.

Vaughn-James, who spent most of his career painting and illustrating, didn’t identify as a cartoonist. He was adjacent to the underground comics scene, not of it. If his work resonates through the medium today, it seems to be in Japan, where, like European albums, “graphic novels” long existed under different names; I can see The Cage in Yuichi Yokoyama’s architectural manga, or the limitless, illusory vistas of Suehiro Maruo’s Panorama Island. Vaughn-James himself preferred “visual novel,” and one of his publishers, chased from sleep with the fear that “graphic novelist” might not sound silly enough, appended the subtitle “boovie.” They weren’t wrong, exactly, even if they were ridiculous. He loved the nouveau roman developed by writers like Alain Robbe-Grillet, all surface, spurning psychology. Vaughn-James’ masterful, disorienting control of temporality is brilliant cartooning, yet it could equally be filed next to Robbe-Grillet’s and Alain Resnais’ film Last Year at Marienbad, where narrative strolls around a country house. Graphic novels appeared before The Cage, but it was the last of something else, a portmanteau that never stuck.