[Read Part One]

Travis Bickle: I don’t believe that one should devote his life to morbid self-attention. I believe that someone should become a person like other people.

- Taxi Driver, Martin Scorsese, 1976

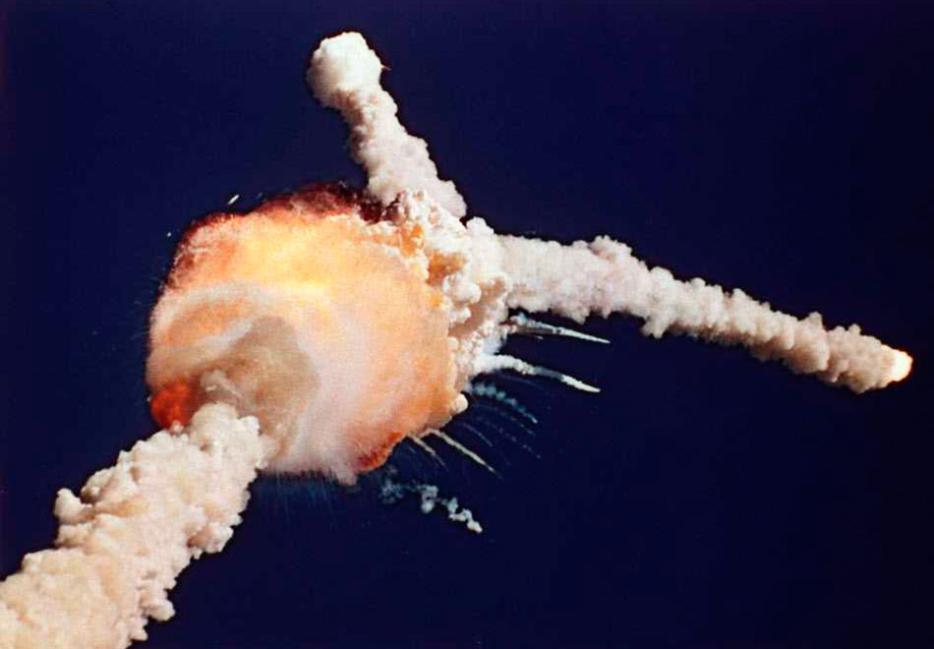

It’s just a plume of smoke, and a beautiful one, at that. This is not the black, inky kind of smoke you’d expect to see when something evil is happening. No, it’s downright cumulus, this plume. It has replaced the Space Shuttle Challenger, launched less than a minute earlier, in your vision. Those assembled at Cape Canaveral are starting to gasp and murmur. If you listen closely, you can hear someone say, “That’s not supposed to happen.”

It takes CNN announcer Tom Mintier a minute. The plume, blossoming against the blue Florida sky like milk in a glass of water, is far enough away that the cameraman struggles to keep focus. This is live, after all.

Finally, Mintier acknowledges something is wrong. “Looks like a couple of the solid rocket boosters, uh, blew away from the side of the shuttle,” he says, then pauses. There is some mental calculus about choice of words. The plume grows, and a fiery something spirals downward away from it. Mintier breathes in, audibly. “In an explosion.”

Moments later, a NASA voice declares “a major malfunction.” The date is January 28, 1986. On board the shuttle with the astronauts is a schoolteacher—Christa McAullife—whose students watched her explode midair moments after the shuttle took off. This is the detail that stuck with me as a kid, probably because my mother is a teacher.

The Challenger Disaster was a historical turning point, not just for the space program, but for failure itself. It was a perfect storm of sorts: CNN was making the 24-hour news cycle a part of people’s lives, while Reagan was trying to revive and re-romanticize the manned space program as the ‘80s hardened around a deep recession. People tuned in to watch the Challenger with stars in their eyes and hopefulness at their breast. And then—bang. For the first time ever, thousands of human beings were watching a large-scale disaster collectively, in real time. A study of the event’s coverage showed that nearly 85 percent of Americans had heard of it within an hour of its occurrence. To us today, that’s nothing, but in 1986 it was extremely significant.

Earlier this week, I argued that the culture and nature of failure are changing. My avatars for failure in the 20th century are the sinking of the Titanic—not only a technical failure, but one of hubris—and Death of a Salesman’s Willy Loman, who resurfaces like a sad, fat iceberg in our consciousness whenever times get tough (notably, each Broadway remount of Salesman aligns with an economic downswing, most recently last season, with Philip Seymour Hoffman as Loman). Both, in their way, have historical links to the Challenger disaster.

When the Titanic sank, newspapers sang its elegy. And although the story spread far and wide for its time, and its romantic pull has obviously remained, only a few hundred souls actually experienced it in the moment and lived to remember: newsreel footage of the boat and its crew exists, but the actual sinking was not recorded. (And newsreels were not yet a staple of the nascent movie house.) While I “remember” its sinking, and laugh about that dude falling and hitting the propeller (thanks, James Cameron), there was never a time where a huge swath of the population felt viscerally, knew now, and saw what it meant when the Titanic failed.

Then came a historical point at which our failures became events. During the Vietnam War, for the first time in history, the news media was on the ground, recording the horror and pain of soldiers (and less so, suffering Vietnamese). Soldiers were also communicating the horror of what they were doing and seeing, and the futility of their actions, narratives held aloft by a newly empowered broadcast media and the protest movement at home.

Watergate piled on Vietnam; the Iran hostage crisis piled on Watergate; the energy crisis piled on Iran. And every night, at 6pm, people could watch this happen on the evening news. This is key. An era of failure once removed became, with the swift kick of the ’60s and its souring into the ’70s, an era of lived, large-scale, institutional failure. (Consider the haunting image of a preteen Sally Draper sitting in front of her TV watching a monk burning to death in season three of Mad Men.) Suddenly, failure didn’t just happen in one’s home or to someone “over there”; it happened to all of us. You could not ignore the fact that the war in Vietnam was for naught, because it was constantly in your face. At the same time, the hippie movement took a contrary stance which embraced the ramshackle and confronted the sad and strange.

This leaked into mass media, first in the form of hysterical news coverage about the kids these days and then, gradually, as total permeation, man. Comparatively, the hankie-waving, “Is Mrs. Astor okay?” coverage of the Titanic disaster is downright ignorant: dig in a little, and you’ll fail to find the headline TRAINED SAILORS HIT A PRETTY SMALL ICEBERG WITH COMPARATIVELY GIANT SHIP. There was observance of tragedy, yes, but little in the way of investigation.

But back to the 1960s: As failure became ubiquitous, culture rose to meet it. Turning away from Willy Loman, we ran face first into Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle. Loman is an inert balloon, the air slowly seeping out of his life, while Bickle is a bullet burst through steel—a loser who refuses to lose, a disturbed war vet with a chip the size of history on his slim shoulder. Failure personified; failure grabbing failure by the disemboweled guts. Bickle does not shuffle about like Loman; rather he stalks, slinking around New York City’s outer edge until he finally violates its centre. He acknowledges his own failures, his city’s, country’s and world’s, then inhales them as fuel.

The golden age of cinema that Bickle heralded is also a cultural key for failure: the studio system and its mores had failed; directors, formerly hired guns, took cues from the European auteurs and wrenched the reigns away. Music was not immune—for the first time in history, with punk, it was cool and profitable to be bad at your instrument. No longer were we running to the cinema (to music, to literature) to get away from reality—we were running toward cinema looking to be struck by the real. Street walkin’ cheetahs with our hearts full of napalm, just like Travis Bickle.

From there, failure’s currency only rose. In that same period, pornography went mainstream. This is not an accident: confronted with our failures, social and individual, there were no more white picket fences left to sully. And so we hurtled ourselves into oblivion, embracing our shortcomings with perverse panache. Failure, emboldened, took on a life of its own. Failure, you could say, became sentient.

The Challenger saw us trying very, very hard to succeed, anachronistically. Reagan was trying to reach back to a Golden Age of American Life™; that falling plume was the consequence of his folly. We could no longer touch the stars, and the movie star president was a fraud. Investigations afterward found that NASA’s organizational structure, unchanged for decades, was largely at fault for the explosion (so was an O-ring, Challenger’s iceberg).

By the time the Challenger exploded in mid-air, in front of hundreds on the ground and millions at home, we were ready to be inoculated against the next phase of failure: failure as mass spectacle, as lived event, as monster of our own making. And, with the dawn of the Internet, that spectacle would spill through the cracks to you and me and everyone we know.

[Read Part Three]