Gotta break your neck to see a star in this yard.

- Death of a Salesman, Arthur Miller, 1949

As a child and young adult I was unwilling to fail at anything, no matter how inconsequential. I can still feel the stillness at my core, the godlike control, drawn from perfect penmanship, impeccable grades, a clean room, alphabetized books. The order given to the universe by a perfect line of pencils on a desk still sings: Success, success, success (thank goodness I loved food too much to try anorexia).

More importantly, I remember with acute and harrowing pain the feeling of failure. Failures at that age were nothing, of course, but no less real to a kid as straight-backed as I. When you wall yourself into a type-A tower, after all, you have further to fall. My horror, at seven, of mispronouncing picturesque (picture-skew”) in front of—gasp—adults was, and is, intense. I still prickle under the arms remembering their laughter. I am, right now, sweating.

I’ve failed since, and I’ve even realized the relative inconsequence, in whole-world terms, of adult failures. And while I can still feel viscerally those tiny, ancient mistakes, at some point I finally stopped caring so damn much. So did you.

We fail. Terribly, grandly, wholly. We are all living that dream where we’re naked on stage, and we have stretch marks and bad tattoos and body hair and they’re laughing at us and then we say something racist and shit ourselves. We fail minutely, too, in paper cuts that only start to hurt after the thousandth one. We’ve always failed, and yet contemporary humans celebrate our smudge-like, failure-ridden lives with relentless bravado, on social media, aloud, on television. We’re all ugly, boring, screaming maiden aunts at a wedding running for the bouquet, falling in the cake; we stumble and fall ad infinitum, but we now perceive those stumbles differently—we have forgotten to be embarrassed by them. The very culture around failure is changing.

Humans once placed a great premium on success (read: not admitting to failure), a mode of thinking which arguably surfaced around the dawn of the industrial revolution and reached its apex in the decades after WWII. To fail, after all, was endemic of weakness, a flaw in character, be it individual, collective, or, in the heady days of war, national. And yet fail we did.

In my lifetime, astronauts went from superhumans who had touched the stars to would-be-murderers who drove cross-country in a diaper.

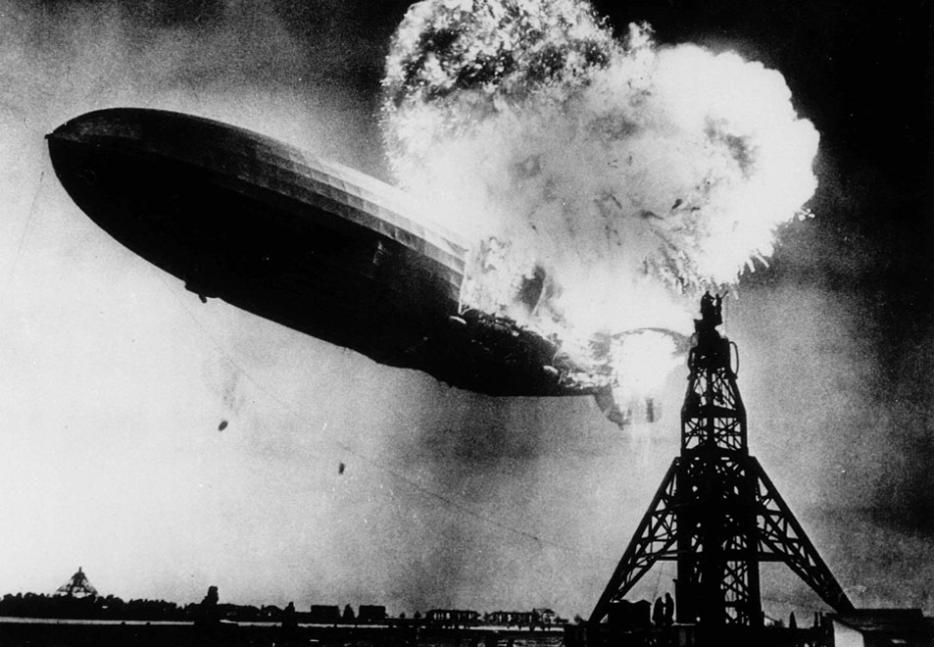

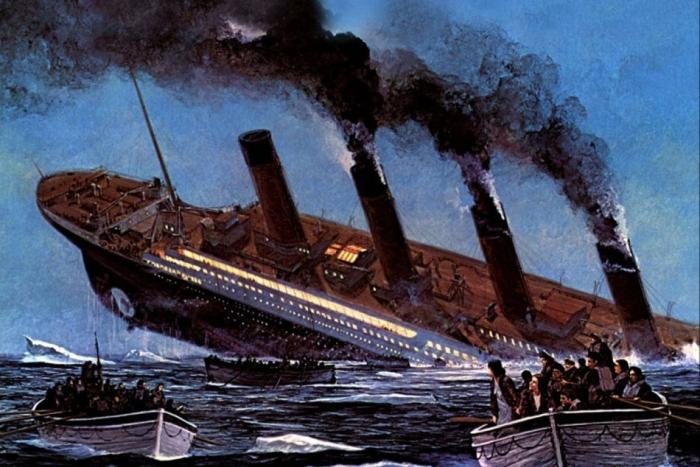

One-hundred-and-one years ago today, the Titantic failed to float. It was Exhibit-A of 20th century failure, the first massive and massively witnessed—via newsreel—misstep in human technological ingenuity (next: the Hindenburg disaster, 1937). Less bombastic but no less important to understanding failure is Arthur Miller’s 1949 play Death of a Salesman, specifically the character of Willy Loman, a human coatrack on which, to this day, we hang our individual shortcomings.

Why these two examples, specifically? They’re signposts in a recent history of human failure which I’ll explore further in part two, but as a preview I’ll say: large-scale failures like the Titanic changed the way we looked at progress. We could no longer pretend human ingenuity and a little coal was enough; mastery over machinery was not a straight staircase upwards but rather one forward, two back. And while art revealed, in time, myriad Loman-types (et tu, Don Draper?), Miller’s play was an anomaly in its age. In popular art—that is film, then rapidly usurping theatre—everything was grand MGM musicals and sunny Doris Day vehicles.

But failure has since shifted culturally, from a point of shame to one of pride. Lately, people are failing more, failing better, accepting and, sometimes, reveling in their failure. Take journalist Jonah Lehrer (he of the fabricated Bob Dylan quotes and self-plagiarism). After being fired from The New Yorker and having his books pulled from shelves, Lehrer in February commanded $20,000 to rehash his mistakes at a Knight Foundation event. In the New York Times coverage, Lehrer was quoted: “If we try to hide our mistakes, as I did, any error can become a catastrophe. […] The only way to prevent big failures is a willingness to consider every little one.” In other words, the larger failure is not admitting to failure—and he cleverly obfuscates his misdoings by suggesting that they’re not that bad if he admits to them (also note the use of “error” and “little” to diminish his acts). In the months since this talk, he’s been much less visible, but should he resurface tomorrow with a multi-million-dollar book deal none of us would be surprised, would we?

The same goes for the political sphere. As I write, the media in New York, where I live, is abuzz with rumors that former US Representative Anthony Weiner—who shared the outline of his erection with a woman on Twitter—might run for mayor. That this is not only possible but probable says a lot about our current capacity for forgiveness. Ditto sports, where Lance Armstrong’s splashy Oprah confession allowed him to draw sympathy from the stone of public opinion—and sell ads for the queen of talk’s dying network at the same time. Sports stars, those heroic paragons, seem to have a particularly intense relationship with failure. Writing about sports scandals in Vanity Fair, James Wolcott said, “The sports pages are where the nation’s true psychodramas rip open and flutter, exposing the hypocrisies we hold dear and destroying whatever illusions we still have hanging around the house.” How insane this is, the amount of ink spilled over a guy who took drugs to ride a bike better than he would have otherwise. More insane: Lance will be back, and we will be watching.

And while we wait, we can busy ourselves with entertainment, particularly talent TV shows, wherein people fail in real time while we enjoy the catharsis of it not being us (not me, though—I’m a wanton sufferer of embarrassment-by-proxy). And if that’s not enough, there’s Lohan, Beiber, or anyone else who has a lot of time, money and fuck-uppery to spare. (Speaking of Lohan and Beiber—gender’s extra pull on this argument has its own dimensions, which I won’t explore here; suffice to say, men seem to bounce back more cleanly in the public eye than women.)

There was a time when sports stars, actor, politicians, journalists were all positions of vaulted class and charm—power—and great pains were made to shield the public from cracks in the armor. In my lifetime, astronauts went from superhumans who had touched the stars to would-be-murderers who drove cross-country in a diaper. And there’s the rub: pulling back that velvet curtain, revealing the shriveled human behind it, has become not only our modus operandi, but a gleeful pastime.

So what changed, and when? All around us, people are failing, falling, flailing—with chins up. It’s harder to hide from failure now, certainly, but there’s something else, something more mysterious. I have theories, and I’m ready to potentially fail at convincing you. But I’ve sharpened my pencils and laid them out neatly. So let’s try.

[Read Part Two, Part Three]