Right as I was congratulating myself for finishing this article, I saw this on my Twitter feed. In sum: ladies, you’re fat because you’re working outside the home. Get back to vacuuming and get back to slim waistlines.

How far have we come in 50 years, babies?

In 1963, Betty Friedan shook the foundations of Western society with The Feminine Mystique, which posited that women might not be fulfilled with only one job option as wives and mothers, that they might not view vacuuming as an ideal source of exercise, and that women can and should work outside the home. It challenged conventions so deeply ingrained they had disguised themselves as common sense.

The Feminine Mystique has become a cultural artifact so powerful you don’t actually need to read it to know why it matters—sort of like how you don’t need to see Star Wars to understand the meaning of “Luke, I am your father.” Beyond its status as a bestseller, the book is credited with launching the Second Wave feminist movement, and a long string of feminist victories followed in its wake: the Equal Pay Act in the U.S., the beginning of no-fault divorce, Roe v. Wade, and enshrinement of gender equity in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Friedan wrote about “the problem that has no name.” In the years that followed, those problems—for they were multiple—were named.

We can see now that the Second Wave movement was deeply flawed: the goals of white, middle-class feminists, of the kind Friedan represented, crowded out millions of other crucial voices. New—and old—issues have captured feminists’ attention since, and as feminism has evolved, so have its primary texts. At Hazlitt, wanted to know: what made you a feminist? We asked dozens of women—most of them 18-30 years old and having come of age during feminism’s third wave—what got them into feminism and why.

The responses ran from brilliant to hilarious to sad—but, importantly, they were all different, proving there is no one-size-fits-all feminist canon. The only way forward is to ask and to listen to individuals; as the Second-wave feminists famously said, the personal is political.

The following responses have been edited for length and clarity.

Sandra Moses Medcof

Magnetoencephalographic researcher, Sick Kids Hospital

I think my first encounter with feminism was likely Mary Poppins. I remember while I was watching it my mom explaining to me who the suffragettes were, and repeating the line of the song that they sing: “Our daughter’s daughters will adore us/ and they’ll sing in grateful chorus/ hats off to the sister suffragettes.” I don’t think I quite got it at the time—I think because it was so hard for me to fathom that women were treated so differently from men and really didn’t have a right to vote. But I remember it very well, and experience is meaningful to me now. I had a similar conversation with my six-year-old daughter a couple of months ago while we were watching the same movie.

Stacey May Fowles

Writer

One of the formative experiences in my relationship with feminism was when my family moved to a hyper-conservative county in Georgia, USA, when I was about 15 years old. Perhaps because there were so many injustices to fight against (the very real threat to reproductive health, for example), the feminist community there was particularly vibrant and active. It was something that I—being from Scarborough, ON—hadn’t really experienced before. It was my first exposure to looking at things through a feminist lens, and gave me the language necessary to articulate inequity, and the tools to fight against it. It of course all happened to a soundtrack of Hole, Sleater Kinney, and L7, which gave me a new sound of female rage to protest by.

I remember teaching at a summer camp and having a fellow counselor give me an issue of BUST magazine (this one to be exact), remember picking up a copy of bell hooks’ Feminism is For Everybody, and Jennifer Baumgardner and Amy Richards’ Manifesta, remember devouring Promiscuities and The Beauty Myth. I came into feminism via more popular, contemporary texts, and was so enthralled that it drove me to do an entire degree reading the classics, like Intercourse, The Second Sex, and The Female Eunuch.

Monica Simpson

Executive Director, Sister Song Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective

One thing that really stands out was the TV miniseries The Women of Brewster Place. It starred Oprah Winfrey and Jakée Harry… it came out in the 1980s. It is possibly one of the most intersectional films about reproductive justice. It definitely had conversations about abortions if women wanted them, and stories about the intersections of violence in women’s lives. Seeing something like that that really became the backbone of the activist I am today.

G. Stegelmann

Writer and Managing Editor, Worn Fashion Journal

My first real understanding of feminism came from Juliana Hatfield and L7, Tank Girl, and working crappy jobs with other young women. In my early 20s I was already wary of “isms” and feminism seemed like another set of dogmatic rules. But when I saw women around me (real and fictional) being loud, or angry, or demanding space in a way that wasn’t about prettiness or male approval, it resonated. I wanted to find my place; I didn’t want anyone telling me what to do. And this light came on that feminism was about being free to live a life on my own terms—and about how important it was we had choices, and recognizing the places where we ought to have had more.

Ayesha A. Siddiqi

Writer

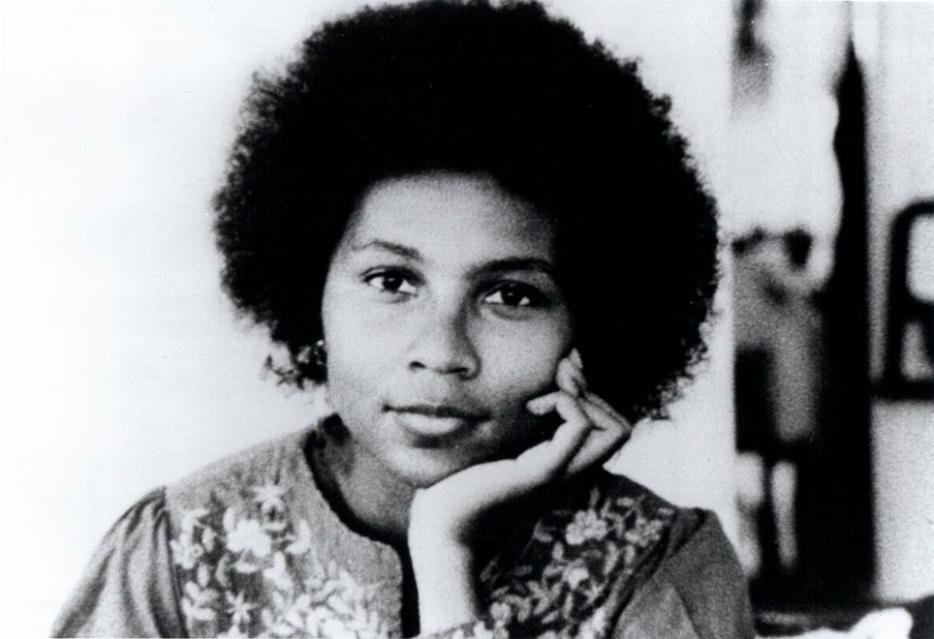

For a long time I grew up understanding the urgency for women’s rights without having a relationship with the word “feminist.” Subscribing to feminism’s ideals felt like the most natural thing in the world. My mother always encouraged female self-reliance, emphasizing education and framing it as empowerment. This framing fostered an awareness for the power disparity across gender that I understood before I even developed a vocabulary for describing it. The works of bell hooks and Audre Lorde were incredibly formative readings for me because they showed me how to confront patriarchy intersectionally, with respect to race, class, and sexual orientation.

But growing up as a woman of colour in the United States, particularly as a Pakistani Muslim subject to any number of horrors the white Western imagination thinks I experience, I’ve seen the failure of Western feminist movements to abandon the racist, imperialist, and capitalist oppressions that distinguish patriarchy. Many women of colour have rejected the term “feminist” for these flaws, choosing instead “womanist.” But I don’t want new words I want inclusivity. Which is why in my late teens I recognized the importance of identifying as a feminist.

Women of colour must create the spaces they are not afforded. For me, it’s achieved by dialoging with the feminism of my American culture and challenging it to be better, by insisting on my participation. By expressing solidarity with womanists in America and around the world whose multifaceted oppression demands an intersectional response. Anyone frustrated by not being heard only guarantees that frustration by keeping silent. So on the anniversary of Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique I find myself looking forward, very certain and willing to articulate that I am a Muslim woman of color, and I am a feminist.