It’s tough not to hate people; they have it coming. But that may be just my self-employment and low income talking. On the other hand, I’m female, Canadian, and kind of a lefty so it’s also easy to love people. Or at least believe they’re not always out to mess with me.

A new study on misanthropy in the American Journal of Economics and Sociology, conducted by Natalia Melgar and Máximo Rossi of Uruguay’s Universidad de la República with Tom Smith from the University of Chicago, compares levels of misanthropy across thirty countries and regions, as well as across a number of socio-economic and demographic variables.

The authors believe that misanthropy—which they define as “hatred, dislike, or distrust of humankind”—is not just the individual grouch’s problem, but responsible for the widespread decay of social networks in many countries. People have liked other people less and less in the U.S. since the 1970s, and the authors are worried that the negative perception of humankind in general makes for less tightly knit neighbourhoods. They relate the rise in misanthropy to a collective loss of “social capital,” which other sociologists have defined as “features of social life—networks, norms, and trust—that enable participants to act together more effectively to pursue shared objectives.” The less we like and trust each other, the less we can band together to run an effective neighbourhood watch, or a community theatre, or a properly synchronized drum majorette group for our parades. You see the problem.

To determine what might affect levels of misanthropy in the individual, the research team analyzed results from the National Identity section of the International Social Survey Program’s survey carried out over 2003 and 2004. It asks more than 25,000 respondents from 36 countries two basic questions:

1. “How often do you think that people would try to take advantage of you if they got the chance, and how often would they try to be fair?” The respondents could answer: “try to be fair almost all of the time,” “try to be fair most of the time,” “try to take advantage most of the time,” or, “try to take advantage almost all of the time.” (The respondent could also say that he or she couldn’t choose an answer).

2. “Generally speaking, would you say that people can be trusted or that you cannot be too careful in dealing with people?” Respondents could answer: “people can almost always be trusted,” “people can usually be trusted,” “you usually cannot be too careful in dealing with people,” or, “you almost always cannot be too careful in dealing with people.” (Respondents could also choose not to select from these options.)

As you might imagine, the answers to these questions varied a lot from country to country. Brazilians were the most skeptical of other people’s intentions, with 36.1 percent answering that people would try to take advantage almost all of the time, whereas the Japanese were the most likely (22.4 percent) to believe that others will deal fairly with them. In response to the question about how much you need to watch your back when dealing with others, Brazilians once again believed most strongly (49.1 percent) that you can’t be too careful in your dealings with others, while Mexicans were the most likely (13.2 percent) to say that people can almost always be trusted.

The researchers also compared the responses across gender, age, income, and level of education, among other factors. Women were generally less misanthropic than men, and young people were generally more misanthropic than older people. I was a bit surprised by this—I had figured that we start out as idealists in our view of humankind and become more pessimistic as life slowly crushes our spirits. The researchers explain this finding by hypothesizing that older respondents formed their view of humanity in simpler times, before everything went to hell. People with low incomes tend to be ill-disposed to others as compared to people who have done pretty well for themselves, and trust in others is highly correlated with level of education.

One finding the researchers highlighted was that misanthropy seems to be closely linked with levels of political corruption in a given country. Using data from other studies, the researchers found that the correlation between the perception of corruption in a country and its answers to the question on fair dealing was 68.5 percent; the correlation between perception of corruption and sense that others can’t be trusted was as high as 79.9 percent. If you can’t trust politicians, it’s tough to trust your neighbours.

The idea that there is an essential human nature—that people are basically trustworthy and fair, or deceitful and out to get you—is one we tend to frame as a theological question: are people basically good or bad? It seems as though the answers may have more to do with economics and political stability than anything universal.

--

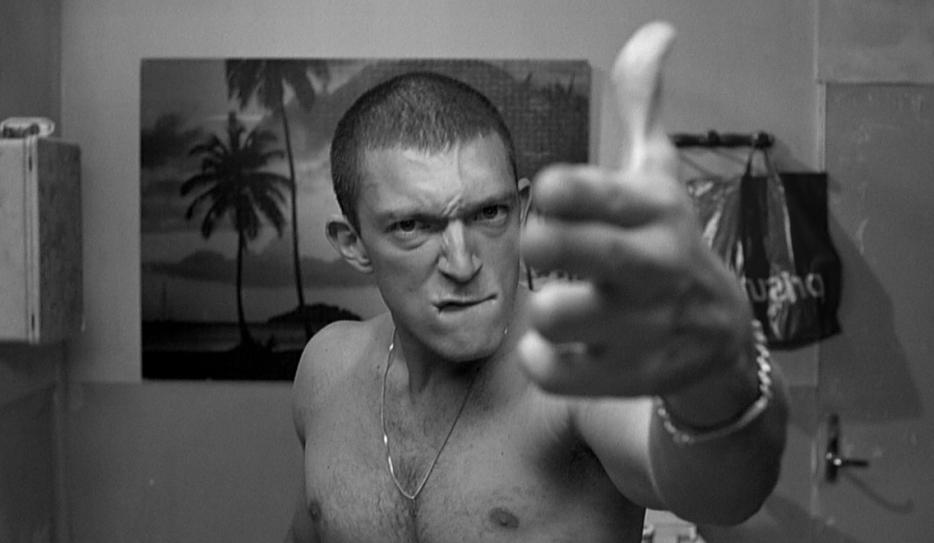

Image: Vincent Cassel in Mathieu Kassovitz's film La Haine.