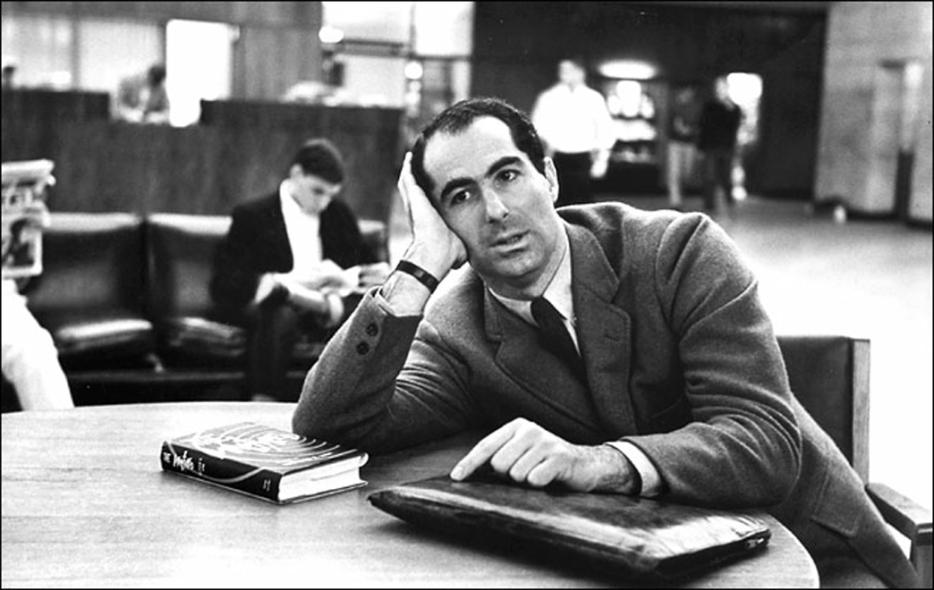

I give it five years until Philip Roth’s comeback novel, but until then let the man have his gold watch. Of fiction, he told the French magazine Les inRocks, “I don’t want to read it, I don’t want to write it, and I don’t even want to talk about it anymore.” There goes the last GMN, or Great Male Narcissist, as David Foster Wallace called the trio of Roth, Norman Mailer, and John Updike: novelists famous for their “uncritical celebration of... self-absorption both in themselves and in their characters.”

Two dead, one retired: a closed chapter in American letters if not for the fact that we still have their literary offspring, a GMN 2.0: writers like Gary Shteyngart, Sam Lipsyte, Richard Ford, Michael Chabon, and Ben Lerner, all of whom come from Roth’s overcoat, or to use a more Rothian metaphor, the smear in his hankie. Of course, Roth didn’t invent the self-obsessed, neurotic crackpot anti-hero. The tradition goes back to Italo Svevo’s Zeno, to Sterne’s Tristram Shandy and, arguably, to St. Augustine, who figured the more he talked about his sins to whomever would listen, the quicker he’d discover God’s grace. But Philip Roth distilled the form.

Nathan Zuckerman, Roth’s fictional surrogate, imagines (over eight novels) a universe that revolves around Nathan Zuckerman. There’s no reason to like him: he cheats, he uses his family as raw narrative meat for his novels (he’s a writer too), his relationships fail because he’s too in love with himself. But we can’t condemn Zuckerman. Why? Because he beats us to it. This is Roth’s great innovation, a character with a skill for Pre-emptive Self-recrimination: he gets away with murder because he admits to his crimes while he’s committing them, and if you value honesty you got to love the guy, even if his honesty is crudely manipulative. He can do what he wants as long as he’s not fooling himself into believing it’s not wrong.

In The Ghost Writer, the first of the Zuckerman novels, Nathan remembers his doomed love for Betsy, a ballet dancer whose commitment to her art allows Nathan the time and opportunity to cheat on her. She finds out, confronts him. He confesses, not just to one affair but a whole slew of them. “I admitted, it was no way to be treating her,” says Nathan, recalling the night they broke up. “But carried away by the idea that if I were a perfidious brute, I at least would be a truthful perfidious brute, I was crueler than was either necessary or intended.” In other words, he admits his mistake—or, in Nixon fashion, he allows that mistakes were made. At the heart of the confession is Zuckerman’s own pre-emptive defense: at least I know I’m an asshole.

And, chastened, he’s ready to cheat again. “He has two dominant modes,” Roth said of Zuckerman to The Paris Review: “his mode of self-abnegation, and his fuck-’em mode. You want a bad Jewish boy, that’s what you’re going to get. He rests from one by taking up the other; though, as we see, it’s not much of a rest.” Bad deeds, confession, analysis: repeat. That’s Zuckerman’s life. As long as it’s all in the service of some twisted form of self-discovery, he gets away with it. And this fetish for mining the self at the expense of all other relationships is exactly what David Foster Wallace was writing against in 1998 in his indictment of the Great Male Narcissists. The post-GMN writers, he said, should worry more about “the prospect of dying without ever having loved something more than yourself.”

Enough with the solipsism, he was calling for what would be dubbed the New Sincerity: people caring about other people (at least in fiction). But instead we got GMN 2.0, the loveable loser schlubs of Shteyngart and Lipsyte, who buy sympathy by copping to their own failings—the slacker sons of Zuckerman. In Leaving the Atocha Station, Ben Lerner creates Adam, an MFA graduate in Madrid on a poetry scholarship who wanders the city doubting that he’ll ever understand anything about himself, Madrid, poetry, women, but mostly himself. His one gift: a poetic talent for Pre-emptive Self-recrimination.

“Although I had internet access in my apartment, I claimed in my e-mails to be writing from an internet cafe and that my time was very limited. I tried my best not to respond to most of the e-mails I received as I thought this would create the impression I was off-line, but accumulating experience, while in fact I spent a good amount of time online, especially late in the afternoon and early evening, looking at videos of terrible things.”

Brooding replaces action (otherwise known as “accumulating experience,” as if it’s rust or mildew) and good intentions are tempered by self-loathing for where those intentions inevitably lead: more porn, less contact with real people. The point is not to achieve a goal but to circle around it until the medication kicks in.

Adam is Zuckerman dialed down to a whisper, less arrogant, more sincere, funnier. Tucked into the character is the author’s affirmation: it’s OK, you’re not alone, none of us know what we’re doing. Which is fine, but going back to David Foster Wallace’s handwringing, is there any room at all for a self-obsessed loser who sees some value in growing up? There might be, but you have to look outside fiction, to television: to the stand-up comedian and sitcom character Louis C. K. He has the Zuckerman gene for self-loathing (“The meal is not over when I’m full. The meal is over when I hate myself”), but his identity is tied up in being a parent: he has daughters, he can’t afford to wallow. If he wallows a five-year-old will get a sunburn or go hungry.

But once we know this, all bets are off: he can say what he wants and get away with it because he cares about his children. “You can tell how bad a person you are by how long after 9/11 you waited to masturbate,” says Louis in his stand-up. “For me, it was between the first and second tower falling down.” It’s Pre-emptive Self-Recrimination worthy of Zuckerman (you think I’m bad, I’ll tell you how bad I am), the gag tempered by the fact that he’s trying to be good for the kids’ sake. You watch Louis C. K. to see if he can resist turning into a Roth character.

That was the drama of Roth’s career: you kept waiting for the character who would get it, understand life outside himself, but it never happened. And that’s the author’s lesson: we don’t understand each other, we don’t understand ourselves. My bet is he’ll be back in five years with the story of the writer who tried to quit but couldn’t, because he still had too much to say. About himself.