Every week or so, Sook-Yin Lee and Adam Litovitz have a movie date. Then they talk about the movie. Discussed this week: Life of Pi, directed by Ang Lee.

SOOK-YIN: I should put this out there—neither one of us has read the book Life of Pi. Although, one time I sat behind Yann Martel in a plane to Saskatoon. When we arrived, a beautiful, young woman with live animals all over her greeted him with a kiss. He gathered his luggage and left with a parrot on his shoulder. I think he’s big into animals.

ADAM: He’s a Noah’s Ark kind of guy, or maybe Jonah and the Whale.

SOOK-YIN: I had an aversion to reading the book, because I judged a book by its cover. I have a difficult time with the anthropomorphizing of animals. The sunny colours of the book, and the smiling tiger on the front—I immediately assumed it would be a sweet-hearted talking-animal story… Before the movie began, there were endless commercials featuring cute animals, the Telus Mobility animals doing cute Christmas things, wearing hats. I thought: oh God, can I deal with this?

ADAM: When I was a kid, I went to see the movie Babe with my parents. Either boredom or nausea overtook my mom, and she walked out, leaving my dad and I alone in the theatre. More than even getting involved in its spruced-up Animal Farm story, I was wondering what about this benign story forced my mom to leave in an emotional huff.

SOOK-YIN: There is something quite horrible about Babe. I had been warned by people to see Life of Pi in 3D, so we put on our glasses. I have to wear prescription glasses to see the screen, so I had glasses on glasses. I was double-framing it. The movie opens with legions of enchanting, exotic animals. I love sloths. I spent a summer watching a very slow-moving sloth in Costa Rica. They’re, dare I say, cute. It tugged at my heartstrings. I got sucked in.

ADAM: I was totally into that. The sloth-hummingbird play at the beginning.

SOOK-YIN: Nature’s incredible. All those rhinos moving in unison. Ang Lee at his best is a very graceful, poetic filmmaker. He knew to have long, luxuriating shots of beautiful animals for the first five minutes. He wowed us with the four-footers.

ADAM: But, the anthropomorphized animal thing can go horribly wrong.

SOOK-YIN: Lee seduces us with gorgeous shots of magnificent creatures and then we realize they’re actually living in a zoo in India. The movie contends with notions of reason and rationale versus dreams and belief. He kept flipping from ultra-romantic images to unfortunate animals in an Indian zoo. The first third of the movie is spent from the perspective of the protagonist Piscine, or Pi, and it’s a child’s point of view. He idolizes his uncle, a fabulous swimmer with an impossibly broad set of shoulders. We’re lulled into the enchanted world of a child exploring faith: thirty-three different Hindu gods, Jesus, then Allah. His quest annoys his pragmatic, realistic father.

ADAM: Some of that felt a little schematic. The first shot when he transitions from being a child to being a teenager is of him lying in bed reading Dostoevsky, later Camus. It goes over-the-top in trying to get us to see him as a “questing person.”

SOOK-YIN: The movie flips between the recollections of a boy and the man he’s become, living in Montreal recounting the story to a writer. I liked seeing Montreal, and hearing him say things like “my family was going to immigrate to Winnipeg.”

ADAM: I didn’t feel like I saw Montreal. Maybe I’m blind, but I felt like I just saw an interior of a house that could have been anywhere.

SOOK-YIN: Sure, that interior could have been built in a Hollywood studio. But, there were shots of the two men walking through the streets of Montreal. They went out of their way to state that it was a Canadian immigrant story, by a Canadian writer. I enjoyed seeing parts of the world I know coupled with moments of a child’s imagination. It took strange hairpin turns. Soon, the zoo’s going bankrupt and dad uproots the family to Winnipeg to open his own zoo. They ride in a boat with the animals stored in a cargo area. When you see the animals downstairs, quickly the enchanted images disappear as dad stuffs tranquilizers in bananas to calm the monkeys down, so they won’t shit too much, ‘cuz it’s a bummer to clean up. It’s the opposite of the romantic animal movie.

ADAM: But it still was a romanticized quest for faith, for god, and for being okay with continuing on. For some reason, it left me cold.

SOOK-YIN: Come on, what about the shipwreck in 3D? That was pretty amazing, right?

ADAM: It didn’t really wow me.

SOOK-YIN: Really? I was like: “It’s a shipwreck in 3D, with zebras floating through water.”

ADAM: I liked the underwater stuff at first, but it became too balletic, more like I was watching a beautiful shot than participating in something gripping.

SOOK-YIN: After the terrible shipwreck, young man Pi is alone, his family at the bottom of the ocean, and he finds himself with wild animals that survived: an orangutan, a ferocious hyena who wants to eat the other animals, a maimed zebra, and finally, this large tiger, Richard Parker.

ADAM: Ang Lee must be obsessed with crouching tigers to have reprised them.

SOOK-YIN: True. When we first see the tiger, he’s crouching and then he pounces. I wonder if Ang Lee was born in the year of the tiger.

The main conflict in the movie is Pi adrift in the ocean with a tiger as travel mate. How do they coexist and survive? I’m looking at this tiger, and I’m reminded of Oscar and Hannah, my dead cats, who I very much loved. Thank god they were as small as they were, ‘cuz they certainly wouldn’t have been as cute if they were the size of a tiger. We’re entering into the territory of Grizzly Man. Herzog’s animal versus man documentary is a rational look at the ferocity of nature. Looking an animal in the eye, are you only seeing your reflection back, your own emotional attachment? Or does the animal want to eat you for breakfast?

ADAM: I found its questions too strictly imposed on me.

SOOK-YIN: You’re sensitive to that. Pi adheres to a three-act structure. It’s essentially a deeper than average Hollywood picture. From the get-go, I think that’s hard for you to take, because you’re aware of the Syd Field story structure.

ADAM: And it started relying on Avatar-like glow-in-the-dark effects as divine light. You have to be okay with flying fish, flying dolphins, and islands full of meerkats. And I’m happy that this festive season involves two coming-of-age Indian-centric magic realist fables—this and Midnight’s Children.

SOOK-YIN: Is that also fable-esque?

ADAM: Definitely. It’s trying to turn the modern history of India into something we can bear witness to through one character’s journey.

SOOK-YIN: It’s interesting that there’s a flavor of India that comes across in Western movies. South Asians are often seen as charming and sweet, intelligent, spiritual, vegetarian and barefoot. I don’t think that sort of depiction would apply to a Cantonese Chinese story. If it was a Cantonese story, there’d be a lot more gambling, squatting, and yelling.

Also, I thought the movie would end like a Disney-fied animal picture, but it takes a distinct turn. It poses an interesting question about the veracity of a story. Is Pi making up a sweet story to cover up an unspeakably horrible turn of events? Would you rather the same event be prettied up and mythologized in beautiful iridescence, or do you want the hard, horrible facts, Werner Herzog Grizzly Man-style? The writer interviewing grown up Pi prefers the story with the tiger.

ADAM: And then there’s the self-congratulatory moment when he says, “that was an amazing story.”

SOOK-YIN: But if you extend the analogy to faith in god, would you rather a nice god in a white robe and long beard sitting in a chair beyond the pearly gates? Or, would you rather know that god is unforgiving and irrational? The writer character chooses the more romantic version without hesitation.

ADAM: I’m not sure that question has any application in my life.

SOOK-YIN: Would you have preferred seeing a romanticized boy’s adventure in 3D, or would you have preferred seeing a brutal, tragic version of the story in 3D?

ADAM: Neither. I think neither one, nor a merger between the two, is something I’m all that interested in.

SOOK-YIN:Why not? The movie is talking about stories. But things like novels and movies reduce life’s strange, chaotic moments to a simple three-act structure, when really life is…

ADAM: Messy, ugly, brutal.

SOOK-YIN: With no particular ending. Unless you say death is the final act. But we communicate our life experience through stories.

ADAM: I don’t. I think I don’t narrativize my own life. It’s totally amorphous and chaotic.

SOOK-YIN: But you like movies.

ADAM: I only like them for their pointed, chaotic moments. I don’t find thematic or narrative cohesion in them.

SOOK-YIN: So, a big thumbs down from you—“no” to sweet animals and humans facing adversity.

ADAM: I prefer something more mercurial. Although, towards the end it tried to create a sense of indeterminacy by suggesting maybe there were two stories at play. But, even that dualism didn’t seem strong enough. I need that sort of spirit throughout an entire movie.

SOOK-YIN: I liked it a lot more than I thought I would. I was wondering, too, if I would prefer seeing an enchanted version or a gritty, docu-story about the cruelty of life in 3D. That could have been interesting, but I think I preferred this enchanted version, at least in 3D. It’s a luxury for the eyeballs.

ADAM: I wasn’t brought to the point of being utterly gripped. The conversation we had yesterday about hope in the face of suicide was more significant to me than the type of hope that this movie tried to instill in me.

SOOK-YIN: We were talking about the time a stranger contacted me when she was about to kill herself and how she and I navigated that moment.

ADAM: I appreciated the simplicity of that story, as just actions and reactions. Whereas, Pi was an over-laboured allegory. And I love allegory. I’ve spent whole semesters in school reading The Fairie Queen with pleasure.

SOOK-YIN: You’re very much your mother’s son.

ADAM: How so?

SOOK-YIN: She walked out of the pig movie.

--

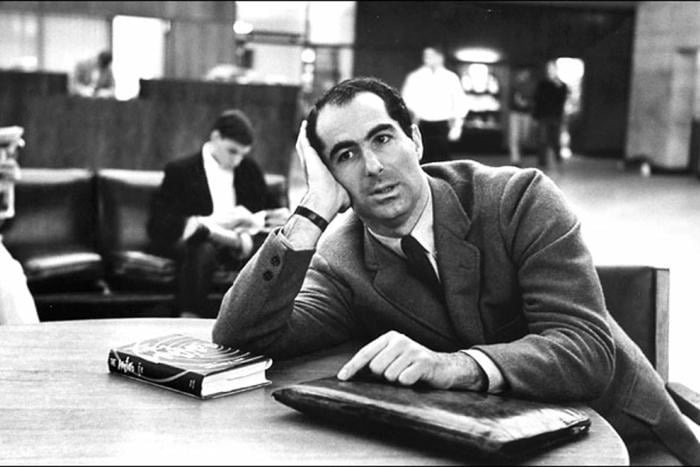

Illustration by Chester Brown