When Adrienne Rich died, in March of last year, at 82, she got the kind of obituary we offer to elder stateswomen: reserved and deferential. But Rich was not your average literary lion in winter—on multiple levels, she was the last of a kind. Nearly all of Rich’s contemporaries—that is, the poets among whom she’d studied and quarreled and found her voice, W.H. Auden and Lowell and Anne Sexton and Audre Lorde—were dead, some of them long gone. And as for the “culture,” or at least what passes for its chief pundits these days, well: they all agreed she was a good poet, but her politics seemed to cow them. They were too direct. The New York Times’ best poetry critic, David Orr, managed the awkwardness by asking a question— “How do we read her work not as social history, but as poetry?”—that Rich would never have asked herself.

That’s not to say she overstated poetry’s importance in directing history. At the New Yorker, the poet and political columnist Katha Pollitt lamented Rich’s departure by remarking that it was “the end of a kind of poetry that mattered in the world beyond poetry.” Yet Rich never quite shared the sense that poetry was held to matter at all. In her own essays, she referred to poetry as “banned in the United States.” Culturally, of course, rather than legally—but called on to clarify, she’d say that poetry had always been an elite practice. And for Rich that was not politically-neutral question. The aversion to poetry, she said, “goes hand in hand with an attitude about politics, which is that the average citizen, the regular American, can’t understand politics, that both are somehow the realm of experts, that we are spectators of politics, rather than active subjects.”

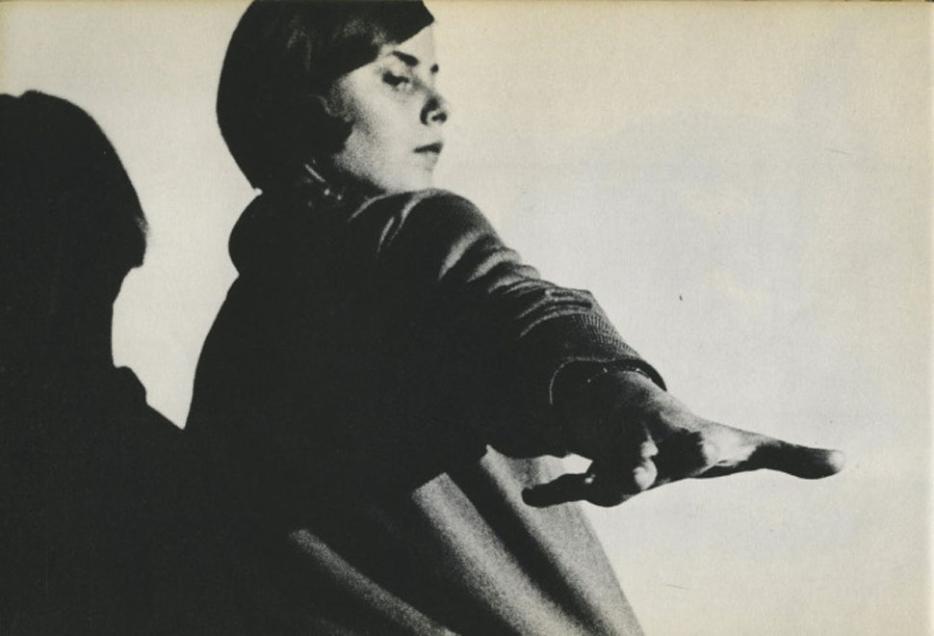

In her own life, Rich refused to accept that these public attitudes ought to guide her. She thus spent her life in what we sometimes call the “margins.” She was a poet in a culture that came to prefer television and video games, and a radical in one that saw Planned Parenthood as a militant organization. She laced her poetry and prose essays with references to the “patriarchy” and “oppression,” which got her called an “ideologue.” For this she seems to have paid a price in glamor, which in a media-driven age is the chief way to get remembered as a poet. There are an avalanche of books and movies about Plath, about the Beat Poets, even about Robert Lowell’s marriages. So much of that is posthumous that perhaps it will happen to Rich, too. But there is something about her that resists it. She might not have wanted such a simple, isolated address of her life.

*

Rich was, ironically, something of a guarded person. In fact Rich always pushed back on the interest her personal life. Writers never do like such questions, of course, but she was particularly quick to shut them down. In one of her last long profiles, done by The Guardian in 2002, she said to the journalist: “I feel there is something frankly sexist about probing my sexual life rather than discussing my work and my ideas. I think that it would not be done to a male poet and thinker.”

The broad outlines of her biography are well-trod territory nonetheless, but they are widely-spaced. Born in 1929, which was, as she once remarked, the year Virginia Woolf gave her famous lecture on A Room of One’s Own, Rich was brought up in Baltimore by a well-to-do father determined that she should write poetry. Her mother was a failed artist, a piano player, and depressed. By 21 Rich had fulfilled her father’s wishes; Auden christened her with a poetry prize that saw her first book, The Will to Change, published. She went on to Radcliffe, where Sylvia Plath envied her meteoric ascent from afar. She studied under Lowell, and befriended him; Sexton too. She married a scholar, a fellow leftist who wrote on the economics of slavery named Alfred H. Conrad, and within a few years had three sons with him.

Motherhood, as an experience, depressed her. Long before we were all screaming about Bad Mommies she was writing very honestly about it. “My children cause me the most exquisite suffering of which I have any experience,” she’d write in her tract, Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution. “It is the suffering of ambivalence: the murderous alternation between bitter resentment and raw-edged nerves, and blissful gratification and tenderness. Sometimes I seem to myself, in my feelings toward these tiny guiltless beings, a monster of selfishness and intolerance.” Eventually she would leave Conrad, in 1970. Perhaps in response—cause is a murky thing—he drove up to their country house in Connecticut, and shot himself in a field. When she chose to address it, Rich did not mince words. From 1972’s “From a Survivor”:

Next year it would have been 20 years

and you are wastefully dead

who might have made the leap

we talked, too late, of making

In another person’s hand this might have been The Event, the thing hashed and re-hashed. Yet he above is one of only two clear references to the incident in her poetry. And even her friends complained, in letters, that they couldn’t fathom what happened. “He always seemed in such full health and discipline,” Robert Lowell wrote to Elizabeth Hardwick, “that nothing pointed this way.” Her friend Hayden Carruth would tell a newspaper, almost thirty years later, “I don’t know what went on between them, except that Alf came to me and complained bitterly that Adrienne had lost her mind.”

The rashness of remarks like that no doubt fuelled Rich’s concerns. After all, her reticence itself was construed as evidence of a “difficult” personality. Unfair criticism thought it was, the reluctance to speak in specifics belied a certain internal contradiction in Rich’s image. After all, Rich’s poetry came out of the feminist movement, a place where the phrase “the personal is political” had become a bit of a cliché, really. Thus to write as a feminist, as a woman, necessarily invites elisions between a narrator and and the author. It’s not too much to say that feminism thought even that it had to be that way, that to speak about politics from a place other than a personal one was dishonest. And really, quite impossible.

It was not so much that she disagreed, but Rich saw things a little differently. She did not deny that there was autobiography in her poetry. But, as she told Fresh Air in 1989: “If you ascribe each event to some actual event, if you ascribe each image, each relationship to some literal occasion, it seems to me that you run the risk of missing not only the poetry, but the fuller, richer, deeper aspects of the poems, which come not necessarily from the poet’s biography, but from what the poet has seen, heard, drawn into herself or himself from other lives.”

From other lives. It’s hard not to see in that phrase exactly what distinguishes Rich from, say, Plath, to whom she’s often compared because both wrote about anger. But Plath was a poet of the interior soul, trapped in an isolation booth. Rich, meanwhile, kept doggedly looking outward. And, keeping in mind what I said about cause and suicide, it’s hard not to wonder if that outer-directedness is what saved Rich, what kept her from being another woman leaving bread and milk for grieving children.

She sometimes seemed suggest so. When Anne Sexton died, another suicide, in 1974, Rich gave a eulogy. And she said, in a phrase that sounds judgmental in our modern terms of compassion for depressives: “We have had enough suicidal women poets, enough suicidal women, enough of self-destructiveness as the sole form of violence permitted to women.” But it was never quite that simple—among the causes she listed for women’s self-destruction, she included “misplaced compassion,” a watchword for the way women had been expected to look out for others, including those, like rapists, who harmed them. “When we begin to feel compassion for ourselves and each other instead of for our rapist,” she said, “we will begin to be immune from suicide.” Love of self and love of world were not so easily separable. One might be embedded in the other.

*

Rich’s process of radicalization did not all take place in the home. She also found herself teaching at the College of New York at a crucial time, as her marriage to Conrad crumbled. The program she taught in had open admissions, meaning no standards; it was called SEEK, which stood for the Search for Elevation, Education and Knowledge. The idea was to allow students who had not been given proper pre-university skills—effectively, in that era, Black and Puerto Rican students, though also poorer whites—some remedial training. In turn, that would give them admission to a college they might otherwise never have set foot in.

For Rich, whose prior history with higher education was near-entirely concerned with Radcliffe, Harvard, Swarthmore and Columbia, students like these had not previously existed. But for her the work of teaching was not a drudgery she endured to fund her “real” work. It was a new challenge to the way she thought: “We were dealing not simply with dialect and syntax but with the imagery of lives, the anger and flare of urban youth—how could this be used, strengthened, without the lies of artificial polish?” That might sound like idealism, like the kind of storyline more familiar to us from Dangerous Minds-like Hollywood banalities. But long before it was sentimentalized, as early as 1972, Rich was writing of that risk and still saying that “the fact remains that our white liberal assumptions were shaken, our vision of both the city and the university changed, our relationship to language itself made deeper and more painful.”

But it was not just students contributing to the learning either. At SEEK, Rich met fellow teachers like the African-American poets June Jordan and Audre Lorde, people who became friends and collaborators and the fellow travellers she elected to spend the second half of her career with. Her dialogue with these women was enormously influential on her view of herself. The first signal of that came when she received the National Book Award for her collection Diving Into the Wreck, Rich walked onstage with Audre Lorde and Alice Walker, saying she wanted to accept it on behalf of all women. They identified themselves as women who “have been tolerated as token women in this culture.”

Though such a statement made few enough waves at the time, if Rich were saying that for us today she’d be accused of dogma and mocked. This is not an abstract judgment. In 1997, when she refused the National Medal for the Arts, because, she wrote, “it simply decorates the dinner table of power which holds it hostage,” pundits had a field day mocking her. Harold Bloom, the old he-critic extraordinaire, attacked her editorship of the “Best American Poetry” in the mid-1980s as being derived from the “School of Resentment.”

In some instances the criticism was helpful, even necessary. Rich was not a goddess with divinely inspired judgments. She, for example, seemed to have trouble speaking to the experience of gender fluidity. She was known to offer support to books like the radical feminist Janice Raymond’s The Transsexual Empire, which likened transgender people to sexual predators who “rape women’s bodies,” though she also was a supporter of the transgender activist Leslie Feinberg. Like everyone else she had contradictions, frustrations, and offhand remarks.

But all that means is what she was—what every person is though these days we refuse to recognize it—is a person with an experience to report, one full of all the foibles and ambiguities we all have and feel. It is not a mistake that her two most famous prose works have that word in their titles: Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Institution and as Experience and “Compulsory Heterosexuality and the Lesbian Experience.” Even she would never have claimed hers was the only one she could or should write about. About those SEEK students, she once wrote, “I think of myself as a teacher of language: that is, as someone for whom language has implied freedom, who is trying to aid others to free themselves through the written word, and above all learning to write it for themselves. I cannot know for them what it is they need to free, or what words they need to write; I can only try with them to get an approximation of the story they want to tell.”

And yet: you tell your story, you gain your freedom, and some people call that politics and not art. As if we all knew already what art was. As if we didn’t know that art could move us in political ways. As if it was worth shutting the door on the inarticulate and the lost for the sake of some abstract quantity called “craft” whose boundaries are exclusively defined by one class of people, the Blooms of this world. Rich’s great insight was that she was not the only person who would, could, or should speak, and she spent most of her time here on earth trying to stick her art in the door to culture to keep it from closing for everyone else. It is truly one of the wonders of the world that for that, she’s remembered as closed-minded.