Why don’t white people think racism is a serious problem?

This isn’t a rhetorical question, but a matter of genuine academic interest. A recent Pew survey asked whether the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri “raises important issues about race that need to be discussed.” 80 percent of black Americans agreed. The plurality of whites said the issue of race was “getting more attention than it deserves.” The survey follows a much-cited 2011 study lead by a Harvard Business School professor that found the majority of white Americans believe that anti-white racism is a bigger problem than anti-black racism. How in god’s name is this possible?

In a recent study, published in International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education this May, University of Arizona professor Nolan Cabrera attempts to learn something about how white male university students feel about race. While there has been a proliferation of scholarship on race in recent decades, Cabrera argues that there have been relatively few critical examinations of whiteness.

Cabrera (who describes himself as a light-skinned Chicano who can “pass” for white) interviewed students from two big, public universities—places he calls “Southwest University” and “Western University.” SWU is 65 percent white, practices affirmative action, and isn’t particularly difficult to get into, admitting about 80 percent of applicants. WU, meanwhile, is just 35 percent white (though it had traditionally been a white school), does not practice affirmative action, and is far more exclusive, taking just 20 percent of applicants.

Cabrera spoke to 43 white male students, then analyzed the reactions of those he defined as “normalizing whiteness.” He found that many students at WU, who were part of a diverse campus, were angry about race. WU does not practice affirmative action, yet many white students still felt that their skin colour had somehow made them victims of race-based policies at the competitive university. “Because of ‘White privilege’ [air quotes], Whites are expected to have accomplished more. And that makes it harder for Whites,” one student told Cabrera. “I mean if you want to succeed in life, you can’t just bank on the fact that oh, I’m Black which means people should take pity on me maybe ‘cause it’s been so hard for me,’” said another. “That’s bullshit!” The students saw race-conscious policies (policies which, again, did not exist) as lowering standards at their university.

The interviewees from SWU were far less aggressive when talking about race. Living in a predominantly white environment, they weren’t confronted with it. Thinking about race was a nuisance more than anything. “[It’s] just that I wish it didn’t even have to be a subject at all,” one student sighed. There was also a tendency to equate race-consciousness with racism itself. “I [grew up] in a very [racially] neutral household in that sense,” explained one student. “We didn’t really discuss race a lot, which I don’t think it necessarily should be discussed a great deal. It shouldn’t be over-emphasized because that’s what leads to racism.”

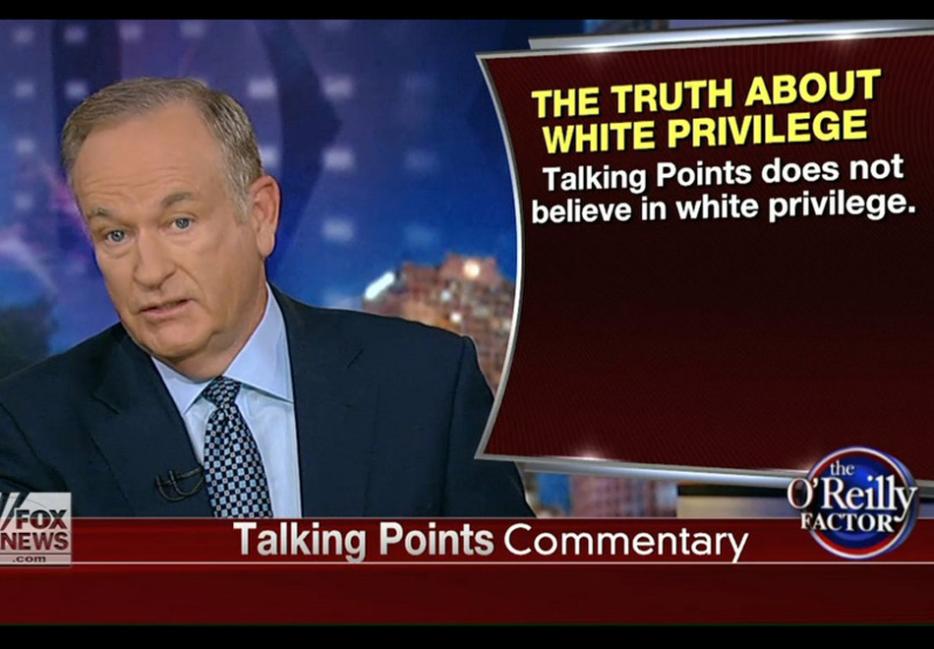

As Cabrera himself notes, the study is too small to make any broad generalizations about The State of White People Today. But studies like these are attempts to understand some of the emotions that underpin today’s systemic racism—the feeling of victimization beneath white supremacy, the way that a self-professed “colour-blindness” acts as a denial of discrimination. Because the attitude at SWU, while less outwardly angry, is in some ways more insidious. Downplaying the significance of racism—acting like the enlightened, rational one in the room while those who dwell on race are a little whiny and perhaps even racist themselves—is a remarkable slight of hand. It goes a little way towards explaining why so many white Americans could possibly believe that “reverse racism” is a dangerous scourge.

Another explanation comes from a 2008 study that Cabrera cites, which found that white Americans were more likely to define racism as “minority disadvantage” than as “white privilege.” This is entirely understandable. No one likes to think of themselves as privileged. Every individual’s personal experience is full of hardships and struggles that feel anything but fortunate—negligent parents, back-breaking summer jobs, persecuted grandparents. Few people match the Tagg-Romney-cartoon image evoked by the phrase “white privilege.”

And so, when confronted with the plain facts of broad racial inequality, you find people like conservative columnist Rod Dreher, who reacted to a recent Ta-Nehisi Coates essay about learning French as an African-American by writing about his own upbringing in rural Louisiana, arguing that feeling comfortable in cultured society is mostly a matter of growing up and developing a better attitude. You get an essay in Time by a young Princeton student called “Why I’ll Never Apologize for My White Male Privilege” recounting the author’s grandfather’s flight from the Nazis. Both pieces could act as supplemental material to Cabrera’s study, which is entitled: “’But I’m Oppressed Too’: White male college students framing racial emotions as facts and recreating racism.”

Of course, there is nothing wrong with keeping a positive self-image, of being proud of your accomplishments and those of your ancestors. The problem, Cabrera argues, is when this self-image prevents you from seeing the world as it is.

Studies Show appears every Thursday.