The New York Kidnapping Club was a kind of reverse Underground Railroad. The group of loosely associated policemen, judges, lawyers, and slave hunters indiscriminately snatched runaway slaves and free Blacks alike and reintroduced these men, women, and children into the American slave market from the 1830s until the brink of the Civil War.

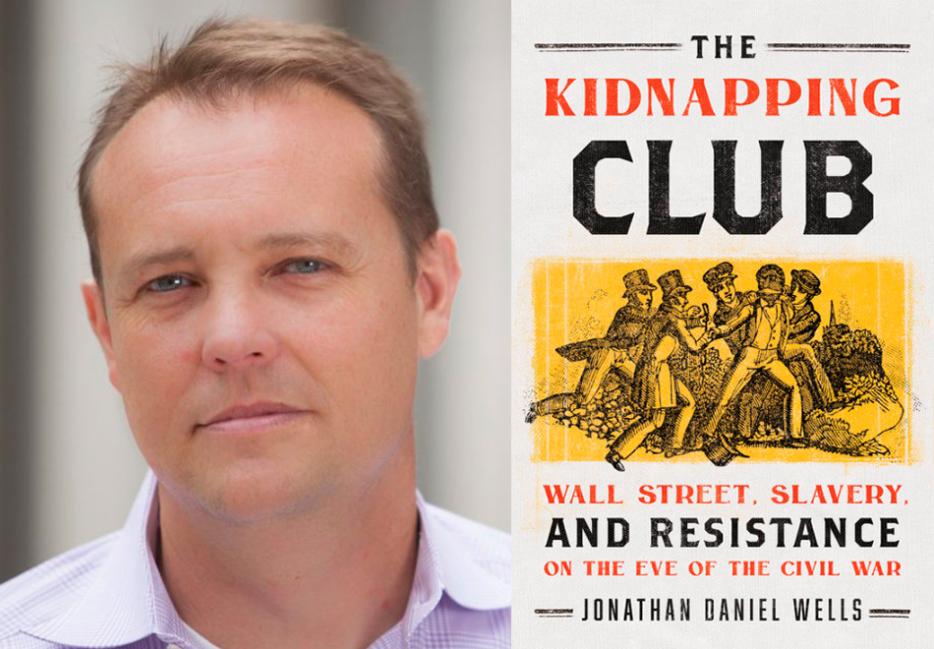

For honoring the Fugitive Slave Clause, which was written into the founding document of this nation—the United States Constitution—slave hunters and other members of the Kidnapping Club collected lucrative rewards from slave owners and, in general, maintained amiable relations with the South. This is but a small fraction of the ways New York City was financially entwined with Southern slavery, as outlined in award-winning historian Jonathan Daniel Wells’ latest book, The Kidnapping Club: Wall Street, Slavery, and Resistance on the Eve of the Civil War (Bold Type Books). Since the early days of the cotton South, New York financiers have been deeply involved in the production of cotton. Banks gave loans to plantation owners. Insurance agencies doled out policies to insure so-called “masters” of their human “property” and of their crops. Seamen covertly outfitted ships for slavers well after the slave trade was outlawed in 1808.

This overlooked history is told through the lens of the impassioned David Ruggles, a tireless Black activist and investigative journalist who waged daily battles with the Kidnapping Club. Seemingly everywhere at once, Ruggles is an excellent entry point to illuminate Wall Street’s relationships with Southern slavery, the political climate around abolition, mounting national tensions around slavery, and a young Gotham maturing into an economic and political powerhouse we know today.

I spoke with Wells about the challenge of narrativizing a history many wanted to keep quiet, what brought moderate Northern whites into the abolitionist fold, and why “New York was the most potent proslavery and pro-South city north of the Mason-Dixon Line.”

Connor Goodwin: I'll start with the obvious. What was the New York Kidnapping Club? In what ways were the actions of the Kidnapping Club sanctioned by law and what legal developments slowed its actions?

Jonathan Daniel Wells: The New York Kidnapping Club was the name given to a loosely organized group of police officers, local judges, sheriff marshals, slave hunters, and lawyers. The one who named this group was David Ruggles, the protagonist of this story. He is kind of the Fredrick Douglass of antebellum New York City—a tireless activist, very committed to racial equality and justice. Ruggles is constantly going up against this group of nefarious actors he calls the Kidnapping Club. For a decade or more, they pretty much terrorize Black women, children, and men in New York City. Some of those people were born free, some of them were self-emancipated. We know thousands of enslaved people did make it to a precarious freedom in places like New York City.

The problem, from a legal standpoint, was that the Constitution, the nation’s founding document, had a piece called the “Fugitive Slave Clause” that required Northern communities to return runaway slaves. Police officers, lawyers, judges, banded together not only to make the Fugitive Slave Clause effective, to follow through on their obligation to the Constitution, but they also found they could make quite a bit of money because so-called “masters” in the South were placing runaway slave ads in newspapers and offered rewards.

Some of the police officers like Tobias Boudinot, one of the arch-villains of the book, as well as Daniel Nash, both profit off the arresting of Black people in New York City. The problem is the Kidnapping Club didn’t care whether someone was born free or was in fact a runaway slave [because] they stood to make money anyway.

Can you outline why Wall Street had a vested interest in upholding slavery and keeping good relations with the South?

In the book I actually write: “New York City is the most potent proslavery and pro-South city north of the Mason-Dixon Line”—Wall Street’s wealth, to a great extent, depended upon the continuation of and the prosperity of Southern slavery. All that cotton being grown up in the South benefits the merchants and financiers on Wall Street. The banks are providing credit to Southern slave owners. New York City insurers are insuring not just against the death of slaves, but also crops. The whole financial institution we commonly think of as Wall Street is heavily dependent upon the cotton trade in the South so they have a financial incentive to make sure relationships between New York City and the Southern states remain rock solid. And they have a strong incentive to make sure the Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution is adhered to, because white Southerners are requiring their property to be returned according to the Constitution. Whether or not someone was born free or born a slave is beside the point in their minds because the overarching goal is to keep the Union intact because that’s the framework for the prosperity they’re enjoying.

When casting around for characters to build this history around, what made you settle on David Ruggles and how did you first encounter him?

What interested me about Ruggles was not just his tireless activism and the fact that he seemed to be everywhere at once in Lower Manhattan, but that he was an imperfect hero. Like a lot of agitators, he rubbed people the wrong way. He wasn’t always interested in making nice, [and] that absolutely made him enemies. Not just enemies with people in the Kidnapping Club, particularly policeman Tobias Boudinot and City Recorder Riker, both of whom hated Ruggles and actively tried to arrest him, but he also made enemies among his fellow Black activists.

[Also,] people didn’t really know much about Ruggles. Everybody knows Fredrick Douglass, but Ruggles was the Douglass of antebellum New York City. He was just absolutely tireless in his pursuit of these cases. He actually ended up sacrificing his own health quite a bit. He was losing his eyesight, suffering physically from all these battles he was suffering.

Can I tell a quick story? Right in the heart of Brooklyn in the 1840s, this Southern family is rumored to hold slave property. Ruggles goes to investigate and finds the rumors are true: the Dodge family from Savannah are actually holding slaves right there in Brooklyn. Ruggles actually records in minute detail the conversations and interactions he has with people—that allowed me to capture a lot of details of the story that would’ve otherwise been lost to history.

You do an excellent job of narrativizing history—from scene-setting to a compelling cast of characters. I'm curious if tensions ever arise when trying to grease history with narrative momentum? I'm thinking of gaps in the historical record, contradictory accounts, etc.

It isn’t easy, that’s for sure. Everybody had an interest in keeping this quiet. The whole nature of running away is really dangerous so it’s not as if the self-emancipated Black people want to record what they’re doing. And of course the Kidnapping Club, while they’re certainly not chagrined by their activity, they don’t want any trouble either. When the Black community gets word of a kidnapping or attempted arrest of a fugitive slave, the Black community mobilizes: they protest, mob court rooms, gather witnesses. The Kidnapping Club wants to keep this quiet and efficient as much as they can.

At the end of the day, sometimes you are left with conundrums, and one of the problems I had with the story I wanted to tell was that Ruggles, who's the hero for the first half of the book, suddenly goes to Massachusetts much to my frustration. He’s suffering so much physically from all these battles and he’s made enemies even among his own friends and colleagues in the Black abolitionist movement that he goes to Northampton in Massachusetts.

Ruggles is the hero, but at the same time he’s a bit of an obstacle to a more sophisticated, more organized, more impersonal abolitionist movement in New York City. As great as he is in fighting the Kidnapping Club, he also kind of sucks up all the air in the room.

Many white Northerners saw slavery as a Southern problem. What moved the dial to bring moderate whites into the abolitionist fold?

We know that, throughout their history, white Southerners are strongly attached to defending slavery. What really shifts is the thinking of white moderate Northerners who have to be convinced there’s something egregiously wrong with [slavery]. The turning point was the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law that’s passed as part of the Compromise of 1850. Now, the issue of slavery is being taken right to the hearts of Northern communities with these fugitive slave captures, the kidnapping, the mobs, the protests. It’s harder to say this is a problem for white Southerners to deal with when, right down the street, a man has been arrested for being a runaway slave and now your city jail is being used to incarcerate the accused and now we have to have a trial to decide if in fact he is a runaway.

The Fugitive Slave Clause was a part of the Constitution, but it really didn’t put any teeth in the law. There’s no way to enforce the fugitive slave arrests and renditions, so that’s why the Fugitive Slave Law is passed in 1850, because white Southerners want some mechanism by which their very expensive property can be returned. I think, more than anything, that’s what convinces a lot of white moderate Northerners. Of course, Black Northerners were completely on board already with the idea that there was something wrong with the Constitution and the Fugitive Slave Clause and the Fugitive Slave Law were immoral and unjust. What convinced moderate white Northerners in New York, to the extent they were convinced because many remain staunchly opposed to Black civil rights, was the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 and the attempts in Northern communities to enforce that law.

This might be a false parallel, but I couldn’t help but think of calls today to abolish the police. Is there any way in which the abolitionist movement you’re writing about might be instructive to today’s activists?

There’s a meme that’s been going around that says something to the effect of, “If you ever wonder what you would have been doing during the Holocaust or during American slavery or during the Civil Rights movement, you’re doing it right now.” A lot of so-called white Americans this summer seemed to all of a sudden realize this, in the aftermath of the George Floyd episode, and that’s why we had white folks as well as Black folks in nearly every city in the country throughout most of the spring and summer. It’s sort of a consciousness-raising and unfortunately, in this case, it seems to have taken the death of George Floyd to raise that consciousness and, in the antebellum setting, it took the arrest of people like seven-year-old Henry Scott or 21-year-old Hester Carr to raise people’s consciousness about the injustices of the way the system was constructed.

The point is to let people know this is part of America’s DNA from its founding, to reveal the ways in which the denial of liberty is as much a part of America’s founding as freedom itself.