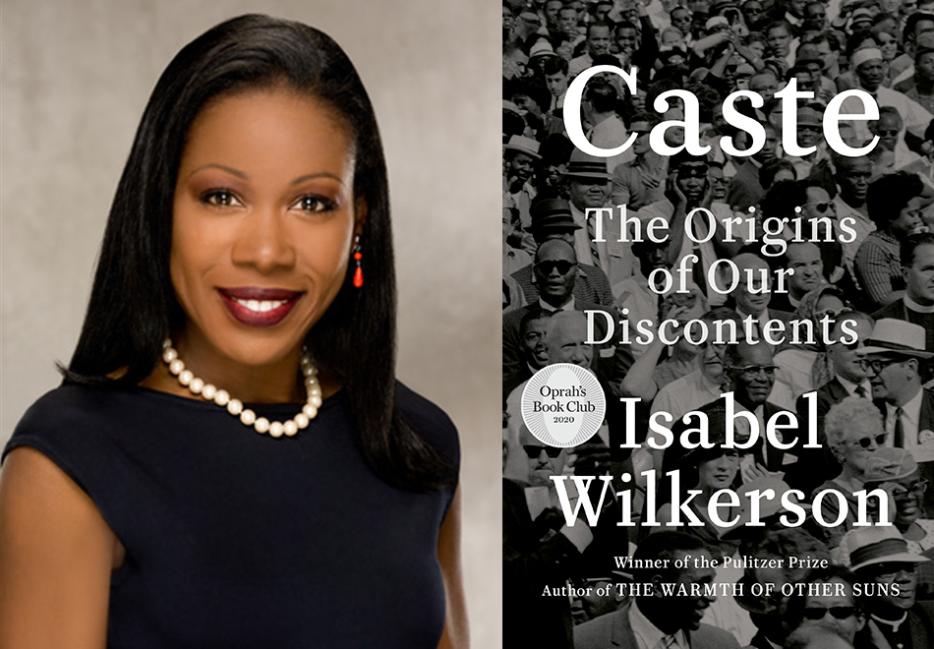

The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson, a Pulitzer-winning journalist, is a landmark study of the Great Migration, the period between WWI and the 1970s when millions of African-Americans fled the Jim Crow South. It was an epic subject and an epic task. Told through the lives of three individuals, Wilkerson spent fifteen years exhaustively reporting and conducting interviews.

Curiously, despite the subject matter, the word “racism” does not appear once in The Warmth of Other Suns. In the course of reporting The Warmth of Other Suns, Wilkerson realized the term was insufficient for describing the elaborate framework that organizes U.S. society. What she was writing about was actually a caste system, and this became the subject of her second book, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents.

Caste is no less ambitious than Wilkerson’s first book. By comparing the racialized system in the U.S. with the millennium-old one of India and that of Nazi Germany, Wilkerson distills what she calls the “eight pillars of caste.” She describes caste as a hierarchical system that assigns roles to members of society at each rung of the social ladder. In a caste system, consciously or subconsciously, everyone knows their place and the place of others simply by looking at them. In a caste system, it is dangerous to act out of place, to break from the script.

I spoke to Wilkerson about how the U.S. caste system was born from slavery and how it has mutated throughout history, her choice to include personal experiences, and why the 2042 census projection, which predicts white people will become a minority, could be a turning point for the U.S. caste system.

Connor Goodwin: I'll begin with the obvious. The U.S. is not usually viewed as a caste system. What convinced you that caste was the best way to frame how U.S. society organizes itself? And what insight does this caste fretwork provide that, say, race or class alone, does not?

Isabel Wilkerson: That’s a great question. It started with my previous book, The Warmth of Other Suns, which was about the exodus of six million African-Americans from the Jim Crow South to all points North, Midwest, and West. In other words, it was the out-migration of people who had been born to and trapped in a caste system known as Jim Crow. I was describing the world anyone [in the Jim Crow South] was living in, whether the people were in the dominating caste or the subordinated caste—and what life was like in that world.

A lot of people who’ve read the book in intervening years have often described it as a book about how they were fleeing racism in the South. But I do not use the word “racism” in the book. Racism did not feel sufficient to describe the organized, multi-layered, fixed repression of the people in that world. That repression was bigger and deeper and more far-reaching than [racism]. So the word I used was “caste.”

[“Caste”] was a word that had actually been used by anthropologists and social scientists who went to the South during the Great Migration, primarily in the 1930s—the word they come up with time and time again was “caste.” So when sociologists and anthropologists went to the South and studied it when the caste system was in full force, in its most formal and brutal iteration, they used the word “caste.” In writing about the experiences of people in the twentieth century who were fleeing that caste system, only to arrive in the big cities outside of the South and to discover a different kind of hierarchy that they then had to navigate, additional restrictions that they might not have anticipated, that actually arose because of their arrival. In other words, fleeing the caste system did not free them from the caste system as it existed in other parts of the country. It shadowed them wherever they went. As a result, the language I have come to use is “caste” because it speaks to the structure, that often hidden and unrecognized hierarchy, and the boundaries that the structure imposes to keep the parts separate and ranked. That is why I use the word “caste.”

What I found most convincing was that a caste system ascribes roles to people at each tier and everyone subconsciously knows these roles. Can you speak to this idea of scripted roles and what happens when someone steps outside their role?

Well, there’s so many examples. Perhaps that is why the word “caste” is so appropriate, because it reminds of just what you said—the roles that we’ve been assigned. We did not choose these roles, they were assigned and affixed to us. In many respects, they hold everyone back because we often don’t get choices as to how we’re viewed, how we’re seen, what our potential is viewed to be.

One of the metaphors I use is that of being in a play. If you have a long-running play, everybody knows who’s in what role, and people have been in the roles for so long they know where someone is supposed to be on the stage before they even step on the stage, because that’s what happens in a play. It’s interesting that the word “cast” is applied to a play; “cast” is what’s put on an arm when there’s a fracture to hold the bones in place. So the idea of holding someone or something in place is a hallmark of what caste means.

The origins of the American hierarchy of caste began with enslavement. Literally what you looked like determined the kind of work that you would do in the country for 246 years of enslavement and then for 100 years after that in the Jim Crow caste system, [which] did not end legally until the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. For most of the country’s history, it was very clear who was doing what based on what they looked like, which signaled where they stand in the caste system.

The dirtiest, most dangerous, most dreaded jobs were assigned to people who were enslaved, who had no choices in what they might do, had no choice over their bodies, and this went on for over twelve generations. Even with Covid-19, studies have found that Black and brown people were getting sicker at a higher rate and dying at higher rates. Much of that had to do with the occupational caste hierarchy that became evident during the crisis, especially in the early going, when there was limited protections, limited masks for anyone. These were the people who were on the front lines: the ones stacking shelves at the grocery store, the ones who were driving the busses and public transportation, the ones making deliveries. They were on the front lines, exposed to the public without the protections we now know were necessary and advisable, and allow[ed] others to shelter-in-place and be safer from the virus.

Every other week there seems to be another example of someone, generally from what would be viewed as the dominating caste inserting themselves or intruding as an African-American is going about their life and calling the police on them for something that would be seen as perhaps benign by someone else. Someone called the police on two African-American men waiting for a friend at a Starbucks. Someone called the [campus] police on a student at Yale University who was studying and resting her head on her books. There’s police being called on people who are at a pool. These are the current-day manifestations of policing the boundaries and the instant recognition of or belief that certain people belong in certain places and others do not.

Is there a way in which the ongoing protests as part of the Movement for Black Lives is challenging the caste script?

I think that all the liberation movements that have occurred throughout American history have been an effort to challenge the pre-existing caste system. This is part of a continuum. History unaddressed recurs. American history is one that can be characterized by the underlying structure that we live with, but then these advances that have occurred over time that were often swiftly followed by retrenchment and backlash and a long period of plateauing. It’s this cycle that seems to be recurring and this is a continuing manifestation of the efforts to bring light to, and to somehow transcend, the hierarchies that have been the basis of so much injustice and inequality in the country.

You speak of caste as a rigid organizing system that seeks to keep the dominant members on top and the subordinate ones on the bottom. While this organizing system is rigid, what constitutes someone as a member of the dominant caste has changed over time. In what ways has the U.S. caste system reconstituted itself throughout history?

The essential hierarchy—the structure—remains the same. But who qualifies to be in the dominant group, who can be permitted, admitted, into the dominant group is one of the focuses of any caste system. The people who qualify to be in the dominant group have changed over time to meet the needs of changing demographics and infusion of people into the country. In 1790, the people who would’ve qualified to be in the dominant group, the people who qualified as white, would be completely different from who would’ve qualified in 1890 or 1924 when a major immigration bill passed that actually restricted people who were coming in from Southern and Eastern Europe and other parts of the world outside of Western Europe.

The fact of a dominant group has been ever-present. The fact of a bottom rail has been ever-present and has been more static in its membership—descendants of the enslaved have always been consigned to the subordinated bottom of the caste system. The changes have occurred in the top.

This is the reason why [we talk about] the idea of race as a social construct. But we have been so acclimated and so socialized to believe in [race] as [a] law of nature that it has come to be seen as the way things have always been. But it turns out race is not actually that old of an idea, only four or five hundred years old. It arose as a concept with the populating of the Americas which brought together people from different parts of the world who otherwise would not have been identified on the basis solely of their color. They would have been identified as Ethiopian or as Polish or as Hungarian and suddenly they get to the United States and they are put in a queue based on what they look like, based on where they fit in the hierarchy that was created as a result of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. People who had not needed to think of themselves as white, not needed to think of themselves as Black, are suddenly assigned to racial categories that did not exist before, that did not need to exist before. This is how relatively new [race] is, but it has been around long enough, become so much a part of how we think of ourselves, we don’t question it anymore.

The language of caste is this new language for understanding ourselves, for understanding our history, understanding how we interact with one another, how we relate to one another, and how we have inherited this framework. No one alive is responsible for creating [and] it’s not anyone’s fault they were born to a particular place in the caste system. This is what we inherited. But once we become aware of it, it is our responsibility to see how it affects us, how it hurts all of us and what we can do to work together to transcend it.

In Caste, you reluctantly introduce some personal experiences. Why did you choose to include these, and did that choice in some way resonate with the recent discourse around “objectivity” in journalism?

The idea of objectivity was not an issue for me. There’s a whole long conversation that could be had about objectivity. We are a species known for our capacity for emotion, for empathy, for taking in information and inputs from many different sources in order to survive. By definition, it means that we are not machines that can be seen as objective. We are, by definition, taking in inputs and sensory information that we then encode subconsciously and consciously that affect how we see a particular thing.

Objectivity is not the same as authority. Objectivity is not the same as doing the research. Objectivity is not the same as doing the hard work to create a document that reflects the research one has done. The goal should be balance. The goal is not to pretend we are machines. We fool ourselves if we think any one person, or any one group, has a lock on objectivity.

My work has always been about telling a bigger story through the lives of other people and not making it personal so that someone would think this is singular to her. I’m more accustomed to and feel very at home with focusing in on the stories of others in order to tell a larger story through narrative nonfiction. That’s what I do, that’s who I am, and that’s what I prefer to do. In the process of doing the work that I have felt called to do, I have also run into the very phenomena I am writing about, so that’s the reason why it seemed necessary, reluctantly for me, to include examples from my own experiences.

Your last book, The Warmth of Other Suns, told the history of the Great Migration through the lived experiences of three individuals. Whereas that book was very biographical and consisted of extensive in-person interviews, your new book relies more heavily on archives and academic studies. How did this affect your reporting for Caste and did it present any unique challenges (like you couldn’t go back for more interviews)?

That’s a really good point. There was a mix of all those things. I did do extensive interviewing and interaction and conversation with people who were dealing with caste in their own ways. The difference is that this is not the same kind of focus on just three people like The Warmth of Other Suns was. This is a chorus of people testifying to the experiences that they might have had of caste. In addition to that work of listening to, hearing, searching out, and being attuned to the stories of people that I was meeting or talking to, I also was looking to the other disciplines that touch upon caste in order to understand it as fully as I possibly could. Anthropology, psychology, sociology, history, economics—all of these various disciplines. I was awash in books. Books, books, books. Books that were written about caste from, say, the nineteenth century. British scholars writing about caste. Indian scholars writing about caste. There was a point where I was having to read a book a day because there was so much coming in, so much that needed to be done. The work was massive to study, absorb, and then distill these disparate cultures, different disciplines, [and] try to condense this into something that would be readable, absorbable, and perhaps illuminating to people.

Throughout the book, you bring up the 2042 census projection, which predicts white people will become a minority in the U.S. In what ways might the 2042 census upset the current caste system and, since it is based on race, how might the caste system reconstitute itself if whites, the dominant caste, become a minority?

The country will be facing a turning point in its identity and it has a choice to make as to how it will move forward, how it will perceive itself, how it will reconcile a demographic combination that it’s never seen before. If projections hold, this will be a new experience for everyone wherever they might be in what I call a caste system.

What I’m trying to say is it will affect everyone and the choice is whether to embrace this change and become stronger for it or to further retrench and reconstitute the caste system as has happened in the past. When you look at the 1924 immigration bill, the response was to shut down additional immigration to keep the country constituted the way it had been. The country is facing an existential question about what it will be, how will it constitute itself, will it embrace a demographic that’s different than what it’s done before. The caste system has been in place from the beginning and has shown itself to be incredibly resilient and enduring and, unless there’s an awareness and enlightenment about that, the possibility is that, without enlightenment and awareness, it will just reconstitute itself as it has in the past.