On October 4, 1931, Dick Tracy proposed to his girlfriend, Tess Trueheart, at her father’s delicatessen. It was a happy day at the deli—Tess’s father, Emil Trueheart, and mother, Mary, had finally saved up enough money to pay off their mortgage, and their girl was to be married to one of the city’s most upstanding and square-jawed young citizens. But there was trouble in paradise: from across the street, two thugs saw Emil counting his money. The engagement party was cut short when they robbed and murdered Emil and kidnapped Tess.

The police arrived, and after a short meeting with Tracy, decided he’d be an asset in their investigation. Just a few panels later, our hero was a fully licensed officer with the plainclothes unit. His comic strip would enjoy a similar fortune: from the Depression through the war years, Chester Gould’s “modern-day Sherlock Holmes” would be the most popular comic strip character of his day, appearing in hundreds of daily newspapers and launching a cottage industry of books, movies, serials, radio shows, and toys. For 45 years, the yellow-suited detective appeared on the front page of the New York Daily News, and the Chicago Tribune used a Dick Tracy contest to increase circulation after its “Dewey Defeats Truman” fiasco.

Eighty-three years after joining the force, Tracy is one of the last Depression-era comic heroes standing, albeit in much lower circulation. Since 2011, the comic has been written and illustrated by Mike Curtis and Joe Staton, lifelong fans whose approach has been playful, nostalgic, and self-aware. Their Tracy is steeped in references to the character’s history, but without the anger that made Gould’s strip a phenomenon, nor the sourness that grew before Gould retired. Somewhere over the course of eight decades, a cultural totem became kitsch.

*

Unlike other comic heroes, Dick Tracy had a gun, and he used it. This made him popular from the beginning: “a symbol of law and order,” in Gould’s words, “who could dish it out to the underworld exactly as they dished it out, only better.” According to Jay Maeder in Dick Tracy: The Official Biography…

The strip was a dark and perverse and vicious thing, sensationally full of blood-splashed cruelty from its first week, the single most spectacularly gruesome feature the comics had ever known. There has never been another newspaper strip so full of the batterings, shootings, knifings, drownings, torchings, crushings, gurglings, gaspings, shriekings, pleadings and beatings that Chester Gould gleefully served up as often as he possibly could.

To Gould, Tracy’s violence was not simply sadistic, but righteous. Born in Oklahoma in 1900, Gould arrived in Chicago in 1921, just in time to witness the city’s rise as a centre of organized crime. He watched Al Capone ascend to power and evade justice, most egregiously for the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre he allegedly ordered. Gould also saw the rise of superstar crimefighters like Eliot Ness, the prohibition enforcer and leader of “the Untouchables.” While eking out a living as an ad artist and editorial cartoonist in the ’20s, Gould pitched dozens of ideas for daily comic strips to the Tribune, but in 1931, “Plainclothes Tracy” was the first to get a nibble.

The hard-boiled detective archetype was familiar from pulp novels, but unique in the comics. Tracy’s villains were based on then-topical figures like John Dillinger, Baby-Face Nelson, Legs Diamond, and Bonnie and Clyde, and the thugs who murdered Emil Trueheart were henchmen of “Big Boy” Caprice, a Capone-like mob boss who dominated the unnamed city. “I’ve always been disgusted when I read or learn of gangsters and criminals escaping their just dues under the law,” Gould said in 1934. “For that reason I invented in Dick Tracy a detective who could either shoot down these public enemies or put them in jail where they belong.”

"The strip was a dark and perverse and vicious thing, sensationally full of blood-splashed cruelty from its first week, the single most spectacularly gruesome feature the comics had ever known."

When the Golden Age of Crime faded and World War II began, Tracy’s villains grew more unusual, and his drawing style more cartoony. In this decade, Tracy first encountered Flattop, Prunceface, B-B Eyes, Mumbles, 88 Keys, and Breathless Mahoney—a rogues gallery as famous in its day as Batman’s is now. “Gould always saw himself in competition with the front page,” wrote Max Allan Collins in The Dick Tracy Casebook. “Headlines were filled with a new kind of ‘gangster,’ the larger-than-life international villain who robbed not banks, but entire countries.” At the height of his popularity, Tracy matched wits with The Brow, a Nazi spy who monitored American ships. In the story’s unforgettable conclusion, The Brow falls off a building and is impaled by an American flag. Dick Tracy was the good guy in a world full of bad ones, and in comics, the dichotomy was never starker.

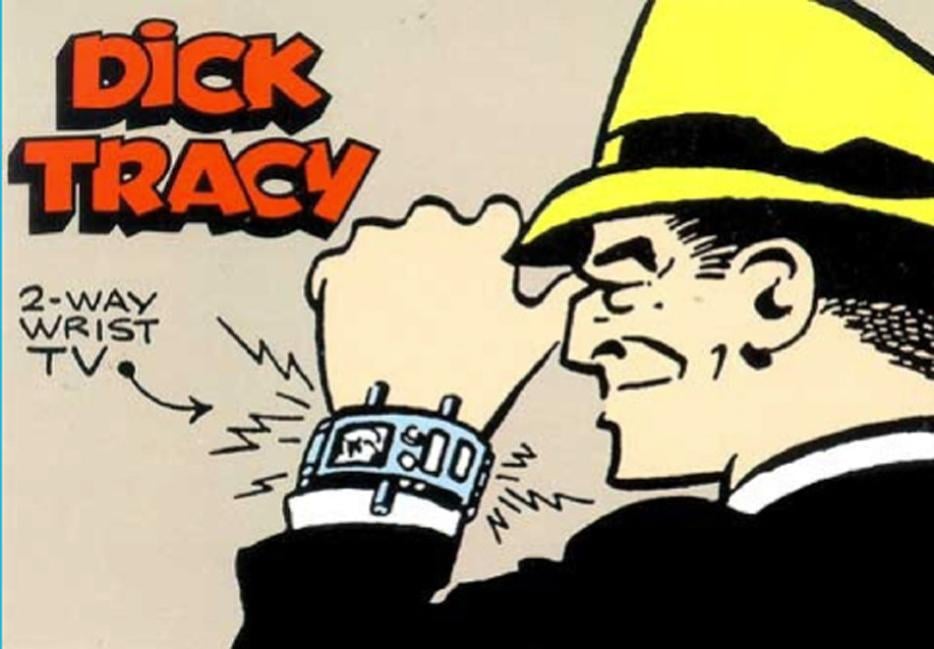

The best Tracy stories, like “The Brow,” rely on a delicate balance of fantasy, realism, and topicality. To stay on the cutting edge, Gould hired police advisors to ensure that Tracy’s crime-fighting techniques were authentic. At the same time, he wanted Tracy’s gadgetry to be ahead of the curve—Tracy had his two-way wrist radio when walkie-talkies were just a gleam in the police force’s eye. But Gould’s obsession with the future of law enforcement led the strip to its most derided era: the 1960s, when the police department built a space shuttle and Tracy took trips to the moon.

“Sure I had gangsters in space,” wrote Gould late in life. “I’m convinced as soon as they’ve established valuable minerals that can be mined in space, there will be gangsterism in space. I irritated NASA a great deal because I brought out things they will be doing in space one of these days.” To be fair, Neil Armstrong did get to the moon. But in Gould’s imagination, the police department equipped Tracy with a magnetic space coupe and air car, and Dick Tracy, Jr. married an alien named Moon Maid.

*

Whatever was happening on the moon, “gangsterism” wasn’t much part of the zeitgeist on Earth. This was an era when police dragged African-American protesters from lunch-counter sit-ins; when vice cops held vigils at Lenny Bruce performances; when the National Guard opened fire on unarmed students at Kent State University, and America staggered forward with its drawn-out conflict in Vietnam; when gay men fought back against a police raid at the Stonewall Inn. Not coincidentally, it was the ’60s when Marvel’s flawed, angst-ridden heroes hit their stride, and when Batman was depicted cheekily in the arch Adam West show. When Andy Warhol painted Dick Tracy in 1972, he confirmed Tracy’s place as a camp artifact.

Dick Tracy was the “good guy” in a world full of “bad” ones, and in comics, the dichotomy was never starker.

Gould wasn’t totally divorced from reality in this period, but the more the world changed, the more staunchly he remained the same. Reflecting on the state of the country in 1974, he said, “You reap what you sow. I think we’re sowing a bad seed in America right now. We’re not instilling the kind of character that made America. We have removed religion. Moral values have deteriorated.” In earlier decades, Tracy occasionally prayed to the Almighty. In 1973, he told a young man in jail:

Jim, your trouble is the world’s trouble. Somewhere in your bringing up, they forgot your compass. They neglected to give you a sense of direction. They left out one important ingredient—God’s Ten Commandments. You got short-changed. Family faith that teaches reverence and respect and peace within, that’s your real shortage.

This sort of empathy was actually unusual for Gould; vivid though his villains were, he hated them. In 1968, Gould began his “Law and Order FIRST!” campaign—the logo appeared in many strips, and remained on his letterhead until his death. He sent petitions to the government against protests, sit-ins, and strikes. There were comics depicting Tracy holding town hall meetings, complaining about “coddling the criminal.” On December 30, 1975, Tracy reported to Chief Patton from the scene of a brutal crime, fuming, “Some way to end the year! A double murder, bank holdup. Two employees dead, a third wounded, has been hospitalized.” Then, directly to the reader: “Crooks engage in capital punishment anytime they want, no court decision necessary!”

“The policeman should be given carte blanche authority to do what his judgment tells him to do,” Gould said in an interview from this period. At this point, he still had an audience—just as Nixon had his “silent majority”—but to Max Allan Collins, who took over after Gould retired 1977, his comments “made the once cutting-edge strip seem to some readers crankily, creakily Establishment-oriented.”

*

Since Gould’s retirement, Dick Tracy has continued under various artists in a handful of newspapers, including the flagship Chicago Tribune. Currently, Mike Curtis and Joe Staton hold the reins, with an upbeat, nostalgic approach that frequently references Tracy lore (they revived the Moon Maid story) and comic history (Tracy has gone fishing with Popeye, and is now investigating the disappearance of Little Orphan Annie). Their Tracy is light, likable, action-packed—though not violent, per se—and its enjoyability is directly proportional to one’s knowledge of the Dick Tracy canon.

Curtis, the writer, says that keeping up with the times is still a priority: they’ve done stories on terrorism, drug smuggling, computer phishing, and DVD bootlegging. Tracy still deals with a crooked legal system, and bad guys still get released on technicalities, but a villain-turned-philanthropist named The Mole is now a successful product of prison counseling. Ted Tellum, a disingenuous radio host, reappears as a Rush Limbaugh-type demagogue. Tracy still celebrates Christmas, but he also visits his partner Sam’s house for Hanukkah. And in their riskiest story, the authors tried a nuanced take on WWII, with Tracy finding a murder confession at a long-lost Japanese internment camp (internment survivor George Takei was a consultant). When I asked about Tracy’s politics, Curtis said he doesn’t know—the detective keeps them to himself.

The last time Tracy held any sway over pop culture was for a few weeks in 1990, when he starred in his first and last summer blockbuster. Released a year after Tim Burton’s Batman, Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy took many cues from the earlier film, with its Danny Elfman score, vaguely retro aesthetic, unapologetic synergism (Madonna sings an album’s worth of songs), and hammy, big-name villain (an Oscar-nominated Al Pacino as Big Boy). For the most part, the film suffered by comparison; it was a moderate box office success, but not the smash Disney anticipated. Beatty still holds Tracy’s movie/TV rights, which is partly why you haven’t seen much of him lately.

Dick Tracy had a lighter, more family-friendly tone than Batman, and while Beatty was praised for emulating the visual style of Gould’s panels, this might be why the film hasn’t endured. Beatty’s point of entry was nostalgia; had he felt strongly about what the character represented, his Tracy might have looked more like Dirty Harry. Burton’s Gotham, for all its excess, was inspired by New York in its pre-Giuliani years. In the opening scene, we see a well-to-do family trying to navigate a street full of punks and prostitutes before being mugged in an alley. Elsewhere, the mayor, a dead-ringer for Ed Koch, is forced to cancel Gotham’s birthday parade when the city becomes too dangerous. With police in the pocket of gangsters, Batman spends his nights pummeling muggers, in the tradition of urban vigilantes like Death Wish’s Paul Kersey. At one point, he literally bombs the factory where the Joker and his goons hide out; in the comics, Batman didn’t kill, but in the film, Gotham is beyond such idealism. If you believe in the criminal justice system, then the “upbeat” finale, in which Commissioner Gordon unveils the Bat-Signal, is deeply pessimistic.

Unlike Tracy, Batman has had no trouble adapting to whatever zeitgeist he’s found himself in; audiences recently enjoyed watching him use illegal surveillance and “enhanced interrogation” in the Dark Knight trilogy. Because he works outside the law, he is not part of the establishment—his very existence suggests the establishment has failed. To believe in Tracy, you need to believe in the good guys.