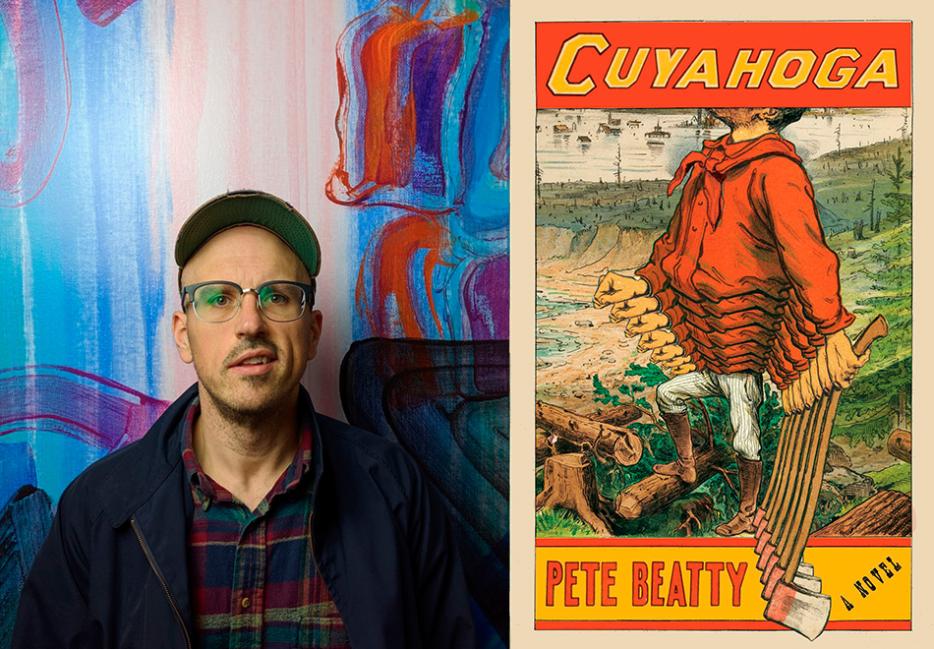

You surely know the names of Davy Crockett and Johnny Appleseed, but do you know Big Son? Big Son, it is rumored, “rastled” a dozen bears, “drank a barrel of whiskey and belched fire,” brawled with Lake Erie for a fortnight and won. These are just a few of Big Son’s feats as chronicled in “Big Son’s Almanac,” a fictitious collection of tales embedded within Pete Beatty’s riot of a debut novel, Cuyahoga (Scribner).

Narrated by Medium Son, Big’s little brother and the bard to his feats, Cuyahoga offers a snapshot portrait of frontier Ohio in 1837, when America was just a tadpole with twenty-two states. Set on the eve of an uneasy union between the sister townships of Ohio City and Cleveland, this novel features a motley cast of characters—enterprising storekeepers barking like carnival hounds, a whiskey-soaked Revolutionary War veteran named Dog, two gasbag mayors, and “spirits” like Big. Separated by the Cuyahoga river, the two townships collide over the question of a bridge and who ought to control it, which leads to such animosity the citizenry of Ohio City take up the slogan, “Two Bridges or None,” as a call to arms.

This squabble over bridges actually happened and is just one of the ways Beatty masterfully blends the elasticity of tall tales with historical fact. This is most poignant in the case of Big, a local hero who is belittled into looking for a waged job because impressive feats, like rescuing maidens from a fire, don’t pay the bills. Told against the backdrop of the financial Panic of 1837, this novel is steeped in stubborn economic realities and unchecked speculative jubilation over seemingly endless real estate prospects and rising industry.

I spoke to Pete Beatty about how he honed the narrator’s distinct, folksy voice, what LeBron James means to Ohio and this novel, why Medium Son is both a merchant of tales and a merchant of death, and what that says about writing.

Connor Goodwin: What most stood out to me was the narrative voice of Medium Son, which is a kind of folksy frontier vernacular with odd grammar. How did you arrive at this voice and what all went into sculpting it just so?

Pete Beatty: The voice is sort of the motor to the book. When I’m unsure where to go next as a writer, I always lean back on the voice and let that be the driver.

The voice of Medium Son is a combination of early 19th-century Southwestern humor, not necessarily what you think of the American Southwest, but the same voice you hear in Artemus Ward, Sut Lovingood’s Yarns, and, of course, Mark Twain. It’s also cut pretty heavily with the Bible; I listened to the New Testament as recorded by Johnny Cash a lot while writing this book. Without realizing it, I think some of that diction, that circumlocutory way of talking, bled into my brain.

There's a class of people in this book called "spirits." How would you describe them and the place they occupy in this fictional world?

The idea of the “spirits” is very deliberately a precursor to a costumed superhero, but also a kind of stand-in for a celebrity. The German word “zeitgeist,” depending on how you want to translate it, literally means “spirit of the times” or “time ghost.” So, it’s someone who, in the case of Ohio in the 1830s, exemplifies or articulates something the people need to summon into existence. The same way Superman reflects the aspirations and imaginations of two young Jewish guys growing up on the far east side of Cleveland in the 1930s.

Also, a big part of this book was—and this sounds a little weird, but—when I started writing it, LeBron James had just come back to Cleveland. Obviously there’s no basketball in the book, but what he represents and how he became this psychological rescuer of a whole region from their self-imposed self-esteem problem was on my mind. He didn’t fix it, but the Cavs won the title and it was a really big deal. It meant a lot and it was all possible because of LeBron.

I love that you brought LeBron James into this. I want to talk more about Ohio in a second, but before I get to that I’d like to ask why you chose to mix the elastic aspects of a tall tale with the more stubborn economic realities of frontier life. The best example of this is Big searching for a job because heroic feats don't pay. You write, “The only income Big had ever known was wonder won by feats." What about this tension interested you? Did you set out to explore that dynamic or was it incidental?

Have you ever heard of the expression “parking by braille”? Where you just bump into the other cars until there’s room for your car? I found novel-writing kind of like this. It was very much a process of guess and check.

I realized I wanted to write this kind of superhero story and at the same time (I was living in Cleveland then) I looked at some history book and saw this (justifiably) forgotten event where two sides of the city got into a fight in the 1830s. That led to me asking what was it about 1837 that made people so uptight? Well, there’s this financial crisis caused by reckless banking and financial reforms made back in Washington, and I started to read everything I could get my hands on about the Panic of 1837. In the 1830s, what was then the frontier, banks were constantly collapsing, so storekeepers would often have a crib sheet and say, based on these banks, these notes are worth this much. The very idea of money was impressionistic. I’m intentionally kind of squiggly on this point—it is a historical novel, [but] I’m not doing history. I did not set out to try and sublimate the fiscal crisis of 1837 into my fiction, but it wound up happening.

Is there any way you can parse for me what historical elements you wanted to remain intact and what aspects you were okay taking imaginative liberties with?

What I wanted to capture with some of the more granular historical stuff was the sense of the permanent unfinished nature of American settler mindset. This sense of moving across this vast continent you’re in the process of expropriating for your own purposes and never really finishing anything. A sort of falling-down-the-stairs cadence of American history, where you’re inventing an economy as you go, you’re selling land in these crazy places, [and] every once in a while, the economic system just implodes and everyone’s broke. It’s really hard not to write historical fiction that does not point to some kind of order. To me, history is more like, look at all this stuff going wrong [laughs].

Could you briefly tell me what historical resources you used? Personal diaries? Newspapers?

My dad used to work at the Western Reserve Historical Society and he let me in the newspaper room. I’m not entirely sure I was supposed to be there. Basically I read every newspaper in the mid-1830s they had in the historical society. Most of the newspapers were just ads, but there is a fair amount of news too. I read a fair amount of historical primary sources of letters and correspondence. A lot of it tends to be people trying to convince their friends and family to move to Ohio. So it has this boosterish feel to it.

This is a novel about Big, but it's also about the city of Cleveland. Set on the eve of a union between two cities separated by the Cuyahoga, Cleveland and Ohio City, the two sister towns squabble over bridges and the possibility of a union. Can you briefly summarize the history behind the city of Cleveland as it appears in the book? I’d be curious to hear if that uneasy union can be detected in the Cleveland that exists today—like, is there beef between the East side and West side of Cleveland?

Like a lot of post-industrial cities—Detroit, Toledo, Buffalo—Cleveland’s rationale for existence is location. It’s at the mouth of this big navigable river that connects to the Erie Canal system, so it’s a reasonable place to bring the ore from Lake Superior to Cleveland to use as steel. Turns out it’s not that sexy or cool to be on the Erie Canal in 2020 as opposed to 1820. But the city can’t move. Speaking of that falling-down-the-stairs energy, Cleveland has been downhill since the Great Depression. Government spending after the Great Depression and mobilization after World War II were the only things that juked Cleveland back into growth. Once that spending went away, Cleveland has been losing industry, good jobs, and a tax base pretty much nonstop for seventy years.

When I think of Cleveland, I think of an unfinished place. I think of some place that got so big, so fast, and then, before it could even reckon with its bigness, the ground started to shift underneath its feet. Cleveland is not unique in that crisis, but to me it’s pretty poignant.

As far as the East side-West side thing goes, I think it’s a much gentler rivalry now. In the distant past, when this book is set, people were swinging axes and trying to blow up a bridge.

You present a complex relationship between storytelling and life and death. This is best embodied by Meed, the narrator, who is a merchant of tales, but also of death, because he sells coffins. Tall tales enhance their subjects, making them larger than life. But then you have this line where you say Meed, in writing this almanac of Big’s feats, is also making a coffin for Big. Can you elaborate on this dynamic of writing as a force of life and vitality and of writing as a kind of grave marker?

You’re the first person to mention that line to me—I remember getting that line down and thinking, “Yeah, stories are coffins.” When we tell a story about someone, in a way, we kill them and put up a memorial. There’s a moment in the book I had a lot of fun writing, which is when the almanac about Big is being assembled and people are bringing in all these different versions that Big died. He’s not actually dead. I wanted to have that cartoonish energy of Wile E. Coyote falls off a cliff, explodes, crashes into a wall, and bounces right back. Each one of those little deaths has its own poetry.

One of my favorite pieces of literature is The Iliad. Thirty-three percent of The Iliad is just descriptions of people dying: “gripped by the hateful dark,” “craved far more by vultures than by wives,” things like that. I wanted to stay with that vision in the book, to have death and destruction always sitting in the room.

Slogans of bounty and profiteering are littered throughout the book, evoking a worldview animated by ideas of manifest destiny and a Protestant work ethic. You suggest that writing, too, can be a form of plunder. In what way do you see writing and storytelling as extractive or exploitative?

I’m a white cis dude and I’m presenting a story of settling America. A major part of that story—what happened to the native inhabitants of Northeastern Ohio, and the entire continent, the entire hemisphere—is not mine to tell. In the 1830s in Ohio, there were still populations of Native Americans, and they were actively resisting the government’s attempts to relocate them, and experiencing hate and aggressive racial violence from white settlers. I recently read Claudio Saunt’s Unworthy Republic, which was a revelation for me in showing how closely tied the project of Indian removal was, in the North as well as the South, with slavery and white supremacy.

In a way I feel like if I am going to write about Ohio in 1837, I have a moral obligation to highlight or center what was happening to Native Americans in that time and place. And I feel like I chickened out on that score. If I had to self-psychologize, I’d say I projected a bit of that guilt into that exploitative element of Meed’s storytelling. I tried to avoid that third rail of racial trauma because it’s not really what the book is about. It’s asking different questions. What do you do with a marvelous possession, to paraphrase Stephen Greenblatt? What do you do with the miraculous, the uncanny, with a brother who can leap a skyscraper in a single bound? What do you do with some weird preacher who can raise people from the dead? What do you do with this giant continent that you decided belongs to you?