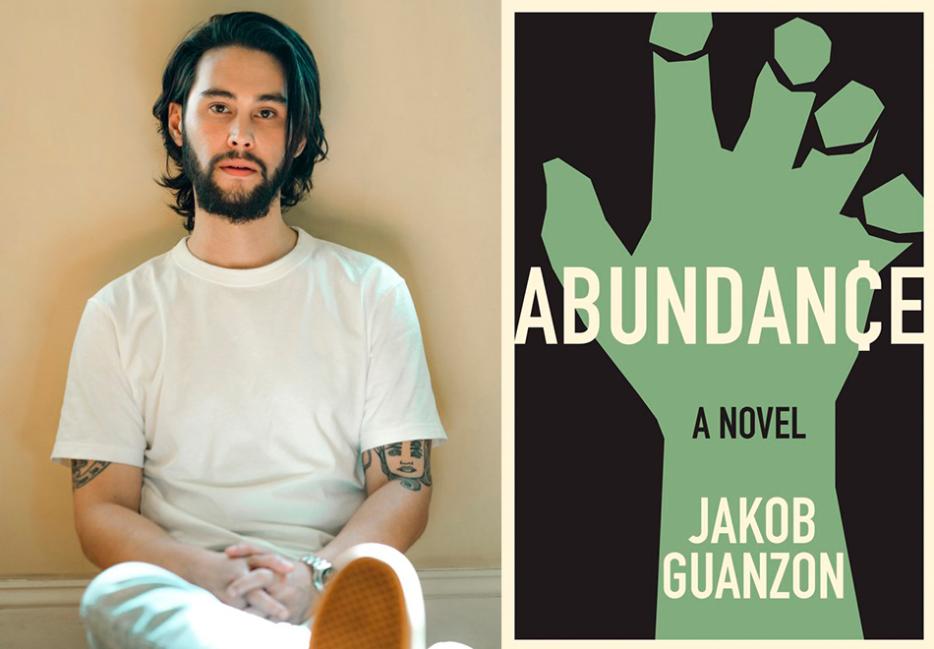

Money is a taboo topic of conversation in our culture, and that silence often extends into literature. Portraits of poverty abound, but relatively few novels discuss money in an explicit or logistical way. In Jakob Guanzon’s debut novel, Abundance (Graywolf Press), money is impossible to ignore. Each chapter begins not with a title, but with the amount of money in the protagonist’s pocket. The first chapter, titled “$89.34,” opens at a McDonald’s where Henry, the protagonist, is trying to stretch every dollar while celebrating his son Junior’s birthday. We see Henry before the value menu, quietly calculating how to optimize his calorie-to-dollar ratio. He washes himself in the bathroom and stuffs a handful of ketchup packets in his pocket, something to tide him over before his big job interview the next day. Newly evicted and living out of his truck, Henry tries to square his shoulders against the indignities of being houseless and unemployed while trying to overcome a checkered past and care for Junior.

I recently spoke to Guanzon about portraying the psychological effects of poverty, writing a story shaped by financial constraints, and how he makes it work financially as a writer.

Connor Goodwin: It’s uncommon to read books that discuss money so explicitly, and money is impossible to ignore in this book. Why did you want to center money in this way, and why do you think it’s not addressed more often in literature?

Jakob Guanzon: I don’t necessarily agree that poverty or people going through tough times financially is new or unique to the canon. I think of Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, a lot of Toni Morrison’s work, up to Shuggie Bain winning the Booker last year.

The one thing I thought was lacking from literature that centers low-income characters—as well as film and TV—is explicit discussion of their actual budgets. We hear characters are broke, or they’re going through tough times, and they might say he’s got twenty dollars in his pocket, but we don’t get the actual logistics very often, if at all, about a character’s financial situation, which is very indicative of our culture. We’re not supposed to ask our coworkers how much they earn, which completely benefits our employers rather than establishing some sense of solidarity. So that was something I really wanted to bring forth, because it seemed to be a very relevant and prominent feature of the experience of both poverty and living paycheck to paycheck.

The last stat I checked, sixty-three percent of the United States is living paycheck to paycheck. Those are pandemic numbers. I don’t know where it was before, but I can’t imagine they were all that much lower just considering the broader economics of this country. When you’re living paycheck to paycheck—which I was up until the pandemic, ironically enough; I’m of the privileged group that was able to keep their job to work remotely, but I’m very aware of that experience of always knowing my budget down to the cent—your spending power is a very specific figure of your human worth in a capitalist society. I really wanted that to be up front and play an active role in shaping this story in the same way that financial constraints dictate a person’s decisions in real life.

You offer some physical descriptions of poverty, but it manifests more strongly in a psychological way—the constant calculations, feelings of shame, endless budgeting. How did you allow readers to inhabit that psychological outlook?

I’m really glad you raised that. I think it’s a very important observation specific to the social utility of fiction of being able to inhabit a character’s thought processes in a way that you’re unable to do in film and other narrative forms.

I really wanted readers to be in the head of a character who’s living through these kinds of situations that readers might have seen on film, but have never had access to their thought processes and to how they’re understanding their surroundings. When we hear about poverty porn, one of the trope depictions of lower-income people is this kind of impetuous, rebellious type who holds a lot of disdain and spite toward anyone at a higher rung of the social or economic ladder, rather than a much more common and truer experience of shame and a sense of inadequacy that comes from feeling totally irrelevant when you’re stripped of the agency to participate in the economy in any real or legitimate sense. That is absolutely dehumanizing and it’s something I wanted to bring to the forefront of how Henry experienced his own little world and how he understood himself.

Reading this, I felt like Henry, in addition to budgeting groceries, gas, and so on, is also budgeting his dreams, ambitions, and emotions—he has to keep these in check at all times. Is that something you also hoped to convey?

Very much so. I don’t want to go into the chicken or the egg of assessing the way Henry processes his personal life versus his financial life in terms of budgeting and calculations, I don’t think that’s necessarily relevant. But I do think they’re totally inextricable when money is really the primary way we assess and ascribe worth and meaning in our culture. Internalizing that into how we conduct ourselves felt really essential. There's a real denial of vulnerability and intimacy that goes into organizing one’s personal interiority in that way.

There seem to be two major emotional poles in this novel, one of which is shame, which we’ve already discussed, and the other is something like pride or dignity. Can you talk about Henry’s relationship to those two emotions?

I think it’d be helpful to discuss them as two separate parts really briefly. Starting with dignity— it’s not a huge request for an individual in the richest nation on earth to have an expectation for and consider dignity a right. I don’t think that’s a tall order. And yet, because of Henry’s social location and circumstances, he’s denied that in almost every minute of his day. He has to stoop to such debasing labor—the labor isn’t necessarily debasing in of itself, but the exploitative nature of how little he can expect to yield from his hours and efforts is—let alone all the interactions he has where he’s constantly feeling inadequate.

When it comes to pride, that really draws from the Filipino component of his identity. The love within a Filipino family goes without saying. You’ve got your loyalty to family, you respect them—that all goes without saying. However, a child really needs to earn a parent’s pride. That’s a huge motivator, but also a huge obstacle for Henry.

You hint at Henry’s Filipino background throughout the novel, but it’s not made explicit until later. Why did you choose to withhold that information?

Revealing a character’s race is a delicate task. The expectation is that non-white characters need to be labeled, whereas white characters can just be assumed by default. So I’m always looking for ways of acknowledging a character’s race without including that in the three qualifiers of like, “He was tall, handsome, and Black." It’s just a bit banal to do that in such a forthright manner. Just as I want to make my prose stylistically as sharp as possible, there’s also an element of how to most artfully divulge demographic factors of characters in a way that doesn’t just sound like the census.

Why did you choose to chop up the narrative the way you did?

When I first started this project, I didn’t think I had the chops to handle a novel, but I did want to write something where a character’s budget was the heading sections of a short story. I had originally conceived of this as a short story within a 24-hour period. That 24-hour arc was what I really focused on writing in the first draft. About 40 pages in, I realized: 1) this definitely has potential to be a novel, but 2) because I’ve established this particular framework [of monetary headings], if I do suddenly drop the [cash] figure to something that doesn’t make sense, the attentive reader is going to pick up on that. So it made sense to include fragmented flashbacks to explain how exactly Henry got into the situation we find him in in the 24-hour track.

One thing splicing up the narrative accomplishes is painting Henry’s character in many different lights—there were times where he earned my sympathy and respect, and other times where I’m like, “Dude, why would you do that?!” What enabled you to complicate Henry’s character in all these ways?

Understanding how desperate and volatile both the situation Henry was in and also how a person is going to respond to this immense pressure and panic in the 24-hour-track storyline, I thought it would’ve been a missed opportunity to not depict that component of his character in other settings where you see him struggling against his own recklessness as a teenager. His immature passion for Michelle as a teenager, the way he conflates infatuation with love, and obsession with addiction. I wanted to have a wide array of examples that are still within the limits of plausibility for his character, but that really show how variegated his emotional spectrum was, to begin with.

Given the subject of this book, I’d be curious to know, and I’m sure our readers would too, how you’ve made it work financially as a writer.

It’s been hard. Unless your parents are bankrolling you, you have to grind like hell. I didn’t decide to pursue writing until my mid-20s. It was always this dream I had, but I had to feed myself. I went to school in Minnesota and graduated in 2011 at the peak of the financial crisis. I couldn’t find a day job, so I was still working as a landscaper, which I had been doing since I was 16. It was hard. All I wanted was a job with air conditioning, and I couldn’t get that with my college degree.

I moved to Spain, was an English teacher out there for five years. I made very little, but learned how to budget and take care of myself. That’s when I was like: you know what, I’m gonna take the plunge. Lived off of boiled eggs and bananas through grad school and, once I graduated, it took about four months to find a nine-to-five job at a big company. Quitting that isn’t happening anytime soon, so I dedicate my weekends to fiction.