The eight masked men and women who took Jean McConville from her West Belfast housing complex flat in December, 1972, had to contend with her ten children. Jean, panicked, asked the kids to help her—they clung to her, wouldn’t let her go until they were reassured that Jean would return in a few hours, and that eldest son Archie could accompany her.

Before Jean was pushed into a Volkswagen van, Archie was told at gunpoint to “Fuck off.” Having little choice, the 16-year-old did just that. Jean McConville was never seen alive again.

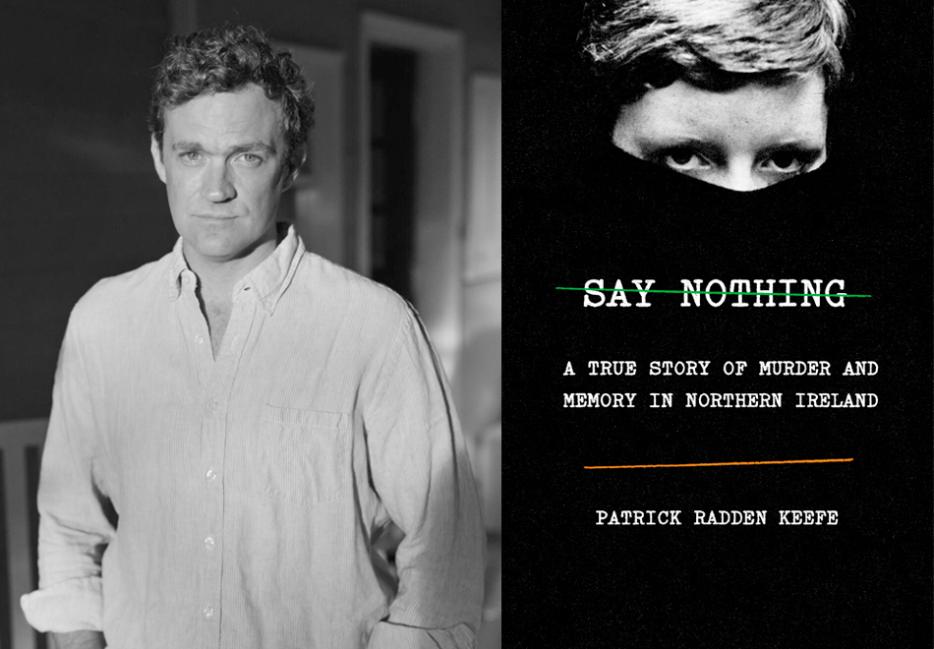

New Yorker writer Patrick Radden Keefe found his way to this story through the obituary of Dolours Price, a former I.R.A. terrorist, who claimed that Jean McConville was an informer for the British army, and was executed by the Unknowns, a paramilitary unit of the I.R.A. Price claimed that the order came from Gerry Adams, who was later to become the leader of Sinn Fein, and a crucial force behind the Good Friday Agreement. Adams has not only avoided claiming responsibility for this crime, he’s denied ever being an I.R.A. member.

In Say Nothing (Doubleday), Keefe has expanded his 2015 article exploring the McConville vanishing into a book that explores the Troubles without making a perhaps-inevitably doomed attempt at being definitive. Keefe’s focus on the McConville crime, and on the journey of sisters Dolours and Marian Price through politics, terrorism, prison, hunger strikes, and decades of consequence, makes for a painful, character-centred story with a truly unexpected ending. Many of the survivors of the recent history that Say Nothing describes seem to want leave it unspoken and unremembered, but they dwell in its aftermath, every day.

Naben Ruthnum: The title—Say Nothing—suggests one of your themes: collective denial. How does this story, and the effects not just of the McConville vanishing, but the entire unresolved trauma of the Troubles—how does denial come into it?

Patrick Radden Keefe: Maybe as a journalist and a writer, I have a bias. My bias is for openness and for truth. I tend to think that you can ignore the past, but that’s not going to make it go away.

That was something that kept coming home for me. This sense of really profound irresolution. In the absence of some process—not even for accountability or justice, but just some truth process. Not even necessarily reconciliation, but just a truth process. To talk about what happened. I do think that everyone ends up in this strange purgatory where they’re unable to move on, and they’re trapped in the past.

The image I always come back to is that moment where [Jean McConville’s son] Michael McConville, as an adult, gets into a taxi and realizes that it’s being driven by a guy who took his mother away. And he doesn’t say anything. And the guy doesn’t say anything. Neither of them say anything, and the guy drops him off.

There’s a metaphor in there, and it’s a metaphor of paralysis.

Addressing this paralysis—in a sense, just getting anyone to talk to you, especially in the wake of many people involved with this story having been compromised by supposedly locked, archival interviews they conducted with Boston College being given over to the authorities—just having people speak to you about the McConville case must have been difficult.

It was different [from the Boston tapes] in the sense that people knew that this was going to be public. Initially I was writing a magazine article, then the book. It was a slow process. Some people never did talk to me. Some people started talking and then changed their minds. And others, slowly, I persuaded them I was responsible and wanted to tell the story as truthfully as I could.

It’s funny. I’d written this 15,000-word magazine article, and with some people, that hurt me, but with others, it helped. I had a calling card, I could say to people, “Look, this is my approach, the book is going to look something like this.” Most people, when they read that, thought, “Okay, he’s serious, he’s thorough, he doesn’t necessarily have a particular ax to grind.”

But not everyone. Gerry Adams was not more likely to talk to me after reading that piece.

The people who did begin to speak to you and then took it back—how did you treat those interviews, ethically? And practically, if these people had given you information that you could act on?

If we’re on the record, I’m very big on ground rules up front. Part of the reason I do that is to avoid any ambiguity on the other side. You and I are talking on the record right now. Tonight, I might suddenly have some crisis about something I said and call you up and try to take it back. But it’s my view that it’s totally your prerogative, whether or not you’re going to do that. You don’t owe that to me. We had a deal.

The tricky thing with a story like this, is that some of the people you’re dealing with are pretty sophisticated about the press, and others are not. In my general career, there are people I deal with who have publicists and are old hands at this, and others who are real civilians who, in some instances, have never dealt with a reporter before. What I try to do is always be very clear with everyone about what I’m doing.

In some instances, there are people who start talking to you and then kind of dry up, or say they’d prefer not to be in the book. If the deal we had in the beginning is we’re on the record, then I’m disinclined to make changes.

The way I think of it is my only real loyalty is to the truth. We can make a deal, a contract, and I have to honour that. But at the point where I start pulling punches, because I like you and think you’re a nice guy? I’m really not doing my job.

You talk about that New Yorker article, “Where the Bodies are Buried,” being an ambiguous calling card—how it worked in your favour with some people, with others, no. What about being Boston Irish, and having the name you do? I love the brief section in the book where you discuss coming up in ‘80s Boston but not having a particular stake in the Troubles.

Originally, I wasn’t going to be in the book at all. Then I sort of had to be in it, because of the revelation in the last chapter. But the reason [that section you mentioned] is in there is because my English publisher said to me, “You have to talk about your name. People are going to wonder.” What I wanted to do is to raise it up and then swat it aside.

I had thought that it would be more of a thing when I went over there. That unionists would hear my name and think that I came from a Catholic background, think that I had certain loyalties. That didn’t happen at all.

I think there’s a lot of Irish Americans, Irish Canadians too, who feel very connected to the old country. But then you go over there, and... I’m American. Inescapably. I think there was a sense that, when they saw me, I may have this Irish name, but I was clearly an outsider. I was very much an outsider, which actually ended up helping.

It neither counted for me nor against me that my name is Patrick Keefe. Weirdly enough, the fact that I immediately registered as American, not a partisan who fit into the grid there, that actually helped.

In your “Note On Sources” in the back of the book, you write about how so many of the books about the Troubles are partisan. But your interviewees would get a sense from you that partisanship wasn’t part of your book.

Yes. People were more likely to just assume that I would tell the story as I found it.

The identity thing is a weird one. For The New Yorker, I go to Ecuador and write a story in Ecuador, I go to West Africa and write a story in Guinea, I go Amsterdam and write a story on Astrid Holleeder—and honestly, I thought of Northern Ireland the same way. It was no different in my mind. I was a foreign correspondent parachuting in to try to understand the place.

You’re really definitive, in the book, that what you’re writing and what we’re reading is narrative non-fiction. It’s not history. But then you immediately follow that statement by explaining that if you see somebody’s thoughts in the narrative of Say Nothing, it’s because that person told you that’s what they were thinking. You’re emphatic about the lack of speculation in the book.

What is the real crucial difference between narrative non-fiction and history, when you’re writing narrative non-fiction about the past?

I don’t really have any one answer. Part of what I was trying to do with that passage you’re referring to was to defend the book against a certain kind of reading. It could be read as a history book, but: I was very adamant that I was telling the story that I want to tell. I’ve picked a handful of people, I’m going to follow them, tell you about their life experience. This is not a full-spectrum history of the Troubles. Don’t foist expectations on this book that were not my ambitions in writing it.

If I sound defensive, it’s because so much of what gets written, so much of the discourse about the Troubles is so vexed. There’s a tendency, often, for people to really have the knives out when books come out.

So, part of it for me was that. Yes, I don’t talk about Loyalists much in this book. If you want to read about Loyalists, there are plenty of good books for that. Please approach this on its own terms.

That was the genre question. But that flows right into these questions about narrative non-fiction. In some narrative non-fiction, there’s an imperative to try to make everything as vivid as possible and to try to be as close as possible to your characters. And I think sometimes people get a little too conjectural for my tastes. In terms of talking about what people may have been thinking, this kind of thing. So, I wanted to be clear that, if the genre here is narrative non-fiction, I personally don’t want anything on the page that you can’t go to an endnote and see: “here’s where he got that.”

The book was fact-checked by the New Yorker fact-checker. If there were things (and there were a few places where I was a little out over my skis in terms of assuming certain things), he would say—is that really in the source? He would go back to the source note. And I dialed back a bunch of stuff, because it was important to me that everything be grounded in fact.

Were you approaching the true crime element of this as a way to unlock the Troubles, or was it the reverse—that you needed to explain the Troubles to make the crime story resonate?

There was never any intention—the book started and the magazine piece started with me wanting to write about this story. It wasn’t that I wanted to write about the Troubles and then I found the story as a way in. It was always about the story, and if I could get some part of the Troubles—but it wasn’t the primary impetus.

I like writing about crime. I’ve written a fair amount about crime, and it can be useful as a way of looking at communities, and families. It’s almost like little seismic shocks. You have something like a murder, it affects a lot of people in different ways, and you can trace those effects. The idea for the book was: what if you looked at one murder, and you looked at both the victims and the perpetrators, saw the ripples of this one act, but tracked that in time, down the decades.

I’m a little bit uncomfortable with the moniker "true crime." But it’s certainly the case that there are conventions of that genre that are here, and it’s a story about a murder. A lot of the reviews of the book have said, "it’s a whodunit, we find out who did it at the end!" But the truth is, if I hadn’t figured out who did it, people wouldn’t describe it as a whodunit.

That was something that was interesting to me—structurally, it works so perfectly that you did, improbably, find out who killed Jean McConville.

But it was an accident.

I was wondering, in the construction of the book, were you always going to centralize the characters that you did? Or did discovering the killer cause you to go back over the draft, to shift priorities?

This was the weirdest thing: it was never my intention to find out who the killer would be. My big north star writing this book was to approach it like a novel, where there’s half a dozen characters, and if they saw or experienced something, we’d see it in the book. If they didn’t, no. I didn’t want to give you a history of the Troubles where you get obligatory asides.

My feeling was that [Jean McConville’s] shooter was probably Anonymous IRA Gunman #3, and that my reader, by that point in the book, wouldn’t care if I wrote, “And then there’s this guy Joe, who we’ve heard nothing about in the last 300 pages, and it was him!!!”

The weirdest thing was discovering that it was somebody who was already a character. I had this moment where—now that I know that it’s X—I should really go back and build in some foreshadowing. I started going back in the book, and the strangest thing is that all the foreshadowing was already there.

Not being immersed in the history of the Troubles, part of what struck me in reading this, particularly as you’re assiduous about tracking the consequences of these acts, these times, to the current day, is the immense fallout in terms of trauma, of fractured mental health. To isolate just one thing, that the Price sisters emerged from their prison hunger strike with eating disorders.

On the eating disorders thing. Some of what I was trying to do—it wasn’t the impetus for the project—but women have often been written out of the Troubles in a way. Part of what was appealing to me was that Say Nothing was the story of two women, Jean McConville and Dolours Price.

When we think of the hunger strikes, we think of Bobby Sands and these ten men and Long Kesh. The idea of looking at this earlier hunger strike that we’ve heard less about, and seeing the long-term physiological and psychological damage—it was a rich vein.

In terms of the toll? I think there’s a huge amount of trauma. You still feel it there today. Substance abuse has been a big part of that. Alcohol, various types of prescription drug abuse, going right back to the ‘70s, when it was tranquilizers, minor tranquilizers that people were taking in crazy numbers.

There are studies that have been done about trauma passing down through generations. The weirdest thing is that even within these families—in part because of this say-nothing culture where stuff doesn’t get aired out—you have kids who’ve grown up after the Troubles who have residual trauma because they’re surrounded by all these people who are so traumatized.

Asking you that, I felt embarrassed about how little I knew about the Troubles, going into this book—I thought I knew quite a bit about the social context, the outlines of the conflict, but quickly learned I didn’t. How did you balance telling the story you were interested in and affording readers the context they needed for it to coalesce?

That is one of the biggest things I wrestled with. I didn’t want to write something that would read like an encyclopedia. There are a lot of those books out there. The trick of context was: how little context can I give you? That was a process. Some of it happened in editing, just sort of paring back and focusing on the story. Some of it was that thing I mentioned earlier—my rule was that if it didn’t happen to these people, then you don’t need to know about it at great length.

To take just one instance, Bloody Sunday, which is the seminal event of the Troubles, about which whole books are written, films have been made? It’s a paragraph in my book. [The reader]’s not even really there, because Dolours Price was in Dundalk [Gaol] when she hears about it. She’s hearing about this thing that’s happening offscreen.

Fortunately, Northern Ireland is a small place, where everyone knows everyone. So, if you’re just going to follow a few people and see history as they saw it, you can see a lot of history.