“The closest thing to perfection is a relationship unexamined,” remarks Hillary Greene in Fawn Parker’s What We Both Know (McClelland & Stewart), a novel constructed to prevent its narrator from leaving any of her family relationships unexplored. Hillary is a writer who can’t quite think of herself as one yet—but in her new role as caretaker to her famous, literary-legend father, she has a chance to produce a very unique kind of book: her own father’s memoir, assembled and ghostwritten by her hand.

Leaving her life in Toronto behind, and dealing with the aftermath of her sister Pauline’s suicide, Hillary immures herself in her father’s rural home, excavating memories of his abuse and secrets from his notes, files, and increasingly distorted speech. As he fades into dementia, Hillary takes on the task of confronting the truth about her family and herself, and of constructing the last element of her father’s legacy on the page.

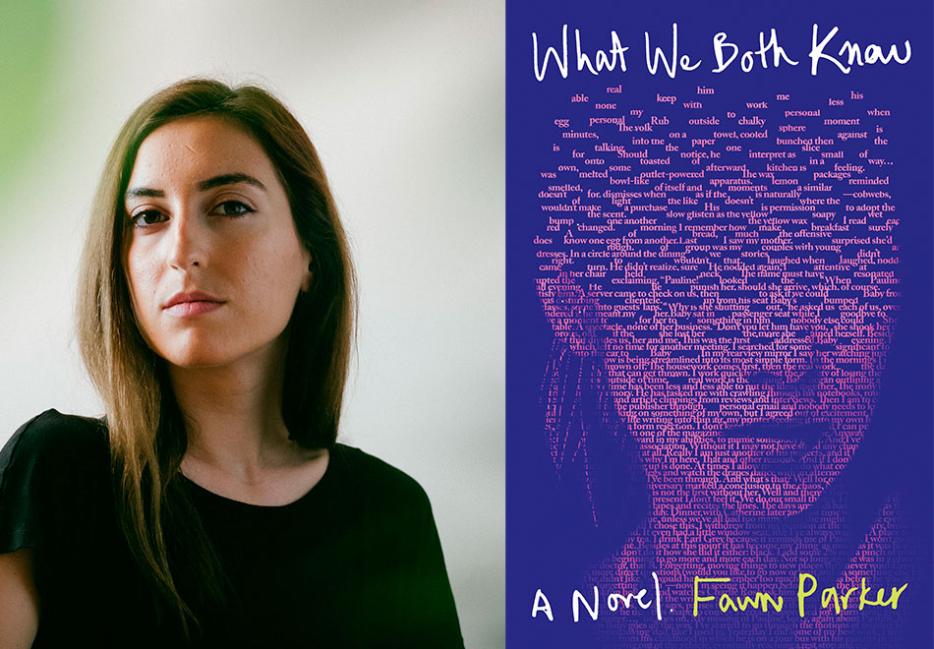

What We Both Know is Toronto writer Parker’s third novel, after two novels with Winnipeg’s ARP Press, both intense examinations of deception, family connection, and the small and sometimes poisonous communities clustered around the worlds of writing both on-campus and off. Parker returns to these themes with increasing precision and genuinely unsettling clarity, in a relentless novel that manages to be both gently funny and ruthless.

Naben Ruthnum: Hillary is tasked with writing her father’s memoir in the book—he’s in rapid mental decline from dementia, and she’s taking his notes to assemble this final book for her father, who had a storied career as a sort of Mordecai Richler or John Updike-like writer—a 20th century “lion of letters” who also, perhaps unsurprisingly, was an abuser. As Hillary performs this task, she’s getting both closer to and further away from her own family story: does this allow her to see herself more clearly?

Fawn Parker: I think that’s one of her fatal flaws: she doesn’t see herself at all. She doesn’t see what’s happened to her, she isn’t really able to look at her life. She describes herself as a terrible writer, and obviously we’re not supposed to think she is, but that might be what’s missing for her (from her writing): she just doesn’t know how to capture herself.

I’m interested in how emotion and connection work in your books—both here and in your first novel, Set-Point—they’re both emotional novels, to me, but skimming the Goodreads I found what I suspected I might: what reads as richly emotional to me is interpreted as cold by many other readers.

I do hear that feedback a lot—even about my own person. It’s important to me, when I’m writing, to not shy away from any emotion, because what I always want to read in a book is the most raw, intense feeling. That’s what a book is to me. There’s something about going at that that does feel cold to some people, and I do see that in the Goodreads reviews—they hate the thing in the book that happens with the dog, they don’t like a lot of the sexual abuse—it’s almost like it reads like overkill, like I’m not being sensitive at all.

Some of it is that—your narrators can be almost clinical in detailing what happens to them. At one point, Hillary says “When I am watched, it is as though I see myself from the outside.” These narrators also seem to write “from the outside.”

I think there’s definitely a distance. I think a lot of my characters are a little bit worn down. They can describe the emotion, but it’s not even affecting them anymore. I like to write a really weary character.

You think that weariness is where a reader might find a gap in emotion on the page?

Yeah. The characters are never going to break down and cry. They’ve already been there, a hundred times.

Are there cathartic moments in this book?

I think so. It always happens in the aftermath, when Hillary is alone and she realizes something, or she goes over something for herself: that’s where her catharsis happens. It’s never really—I don’t think she’s present, a lot, in the moment.

There’s genuine love and affection in certain scenes between Hillary and her father, which is one of the disturbing aspects of the relationship, especially as we find out more about him.

I think it’s really specific to anyone who has loved somebody abusive. You sort of develop a way to split and to love things about them. It can also, sometimes, deepen it, because of the intensity and the toxicity of abuse. It can keep you feeling very alive and very focused. That’s how abusers get people, they’re very charming, charismatic, and lovable in some ways. But I do think that I was signalling to a certain group of people who have experienced abuse—that you do, you do love in that way. I wanted to make this a portrait of dangerous, painful love.

And her father has different relationships to love and sex, including the transactional sexual relationship he once had with his ex-lover Catherine, who remains an important figure for Hillary.

That stems from someone in my extended family, who used to do that. He would bring home sex workers, to the family home, and sleep with them upstairs as the rest of the family would operate downstairs as though it wasn’t happening. I thought that was so disturbingly beautiful, the chaos of that whole situation, the disrespect by the head of the household. I wanted to play off of that, this character from my family, and I wanted to explore what that would be for the sex worker—for Catherine. Who she was, who she is when she’s alone with Hillary. She’s another hurt woman, who admired this man.

You brought up something else I wanted to ask about: Hillary has this sense that something is missing from her writing, that she’s not good, though she does have these little glimmers of confidence. Stylistically, how do you capture the writing of a writer who thinks of herself as incompetent?

I think when she has moments [of confidence about her writing]—she’s able to experience those moments through anonymity. When she’s writing as her father, she can see it as good and bad, because it’s not hers and her name’s not on it. When it’s just hers, she projects her own badness onto everything she touches.

We see her writing as her father in these excerpts you have of the memoir—but the narrative voice, I feel that’s also her writing.

I think so too. I think maybe that part is a little bit of a joke, a bit of self-deprecation: the whole book could be bad. I struggle with that within myself too. With the excerpts from her father’s memoir: I think those were fun for me. They’re gross, they’re hyper-masculine. I wanted it to be something that she could see as embarrassing and over the top.

Part of Hillary’s sense of being an imposter is the way she’s been earning her living for the past few years, before coming to be her father’s caretaker: she’s working an admin role in a creative writing department. She’s around writing and writers but emphasizes that she’s not actually involved.

I wanted her to be stuck. She’s outside of Toronto, where she feels her true life is. She’s not in any sort of real relationship. Her only connection is with Catherine, her father’s past lover. She’s always on the outside looking in, especially in this writing position that she’s in, and I think that’s the place: maybe it’s where I feel I am sometimes, and I wanted to explore that in a more overt way.

Hillary’s father has tendrils all over her life, including that job, and we get this sense that getting her that role in this department that he haunts—he stopped teaching there after a harassment scandal, but the department has never turned on him—it’s part of his controlling, abusive reach.

Something I think about a lot—my previous novel is a campus novel—I think about campus politics and how that world operates. It’s not really changing at all: we keep firing men and then hiring new ones and firing them. Hillary has that moment where she reaches out to the coordinator and he just defends her father. It seems like satire, but it does seem to me like what’s actually going on.

I keep saying “Hillary’s father” because he goes by a couple of names in the book: his “real” name, Marcus Greene, and the name he used throughout his writing career: Baby. What are the origins of this pseudonym?

That’s my dad’s name. He’s also adopted, he’s nothing like this character, but his birth name as a foster baby was Baby Davidson. They just give you the surname of the biological mother and the first name is Baby. I thought that would be so funny for a grown man to have to revert to this name because he’s ruined his other name, Marcus Greene, in his agent’s eyes.

I like the part of story of how he “ruined” his name; it’s one of the lighter parts of the book. Can you talk about that?

He had this past as an anarchist poet in undergrad, under his real name. He was in a troupe of writers called the Arthurs, who published a literary magazine, or zine. His agent wanted to sell him to New York as a big, American-style writer, so they tried to kill off that true identity and make a new one out of his previous identity.

It’s the Arthurs troupe part that I especially enjoyed—what part of literary culture were you touching on there?

That just feels so CanLit to me, and hopefully that doesn’t sound like an insult. I love the idea of the Arthurs, even though I make fun of them. Canada’s so… no one ever wants to make it, and in previous generations it feels like there was so much collaboration and teamwork, and communities of people who really focused inward. You’d see the same people at every reading.

I love the way that it operates, especially the Ottawa/Toronto/Montreal little cluster, and I think that it’s so different from the way that people who do make it to New York blow up, like Baby. The Arthurs are what I love about the writing scene.

And you are involved in community things—not exactly in a troupe, but you’ve run reading series, and even represented authors?

Oh God, yeah. I tried to. It didn’t go very well, but I did want to. I think I was doing more harm than good, but I tried to help.

How did you do more harm than good?

I just didn’t sell a book. I tried to be an agent for a year and a half. I edited some contracts, so maybe did some good there, but I told myself that if I didn’t make a sale by the end of the year, it was over.

What gap were you trying to fill?

It’s sad to me than there’s no representation for poets, and there’s no representation for small press authors, and it’s so hard working with small presses—and hard for the presses too, because those houses are always operating on grants. But for the authors, they’re signing option clauses and they don’t know what that means, they’re getting $500 advances at best… I just wish that everyone had a little bit of a cheerleader with them, helping out.

What could read as condescending about the Arthurs—which didn’t, to me—comes from a genuine fondness for this kind of community.

Yeah. I do love it, and I kind of make a mockery of it. I kind of exist in both worlds, which is maybe a bad thing.

Baby’s celebrity was another thing that I got stuck on, because there’s something nostalgic about it, like this memoir is not only a remembrance of his life, but of a literary life that’s increasingly rare. The kind of celebrity that Baby has is increasingly rare, boutique—what new writers have it? Sally Rooney, obviously, but it’s a very short list if we think of people in their twenties and thirties…

And the ones who are there, it’s more fleeting, and I think because we all have access to this big conversation it’s more nuanced than just celebrity or not. I don’t think there is a Baby Davidson figure right now.

I think it also has to do with the fading cultural primacy of literature… which obviously concerns me. You too?

Absolutely. It’s all I have, literature. It simultaneously concerns me and is quite beautiful, because as the group of us narrows, the connection becomes more intense. I’m so excited when I meet other writers who really love writing and literature.

Aside from the authors, there’s a constant humour to What We Both Know: certainly not a jokiness, but moments of comic remove that both break and deepen the sadness.

My approach to humour is to demonstrate the things I think are so funny about people. When I write a character, I want them to exist in the humour. I don’t want to write a character who’s going to tell jokes—I know sometimes I do that—but I think the funniest thing is just the nuance of how people form a sentence, and the strange things they do.