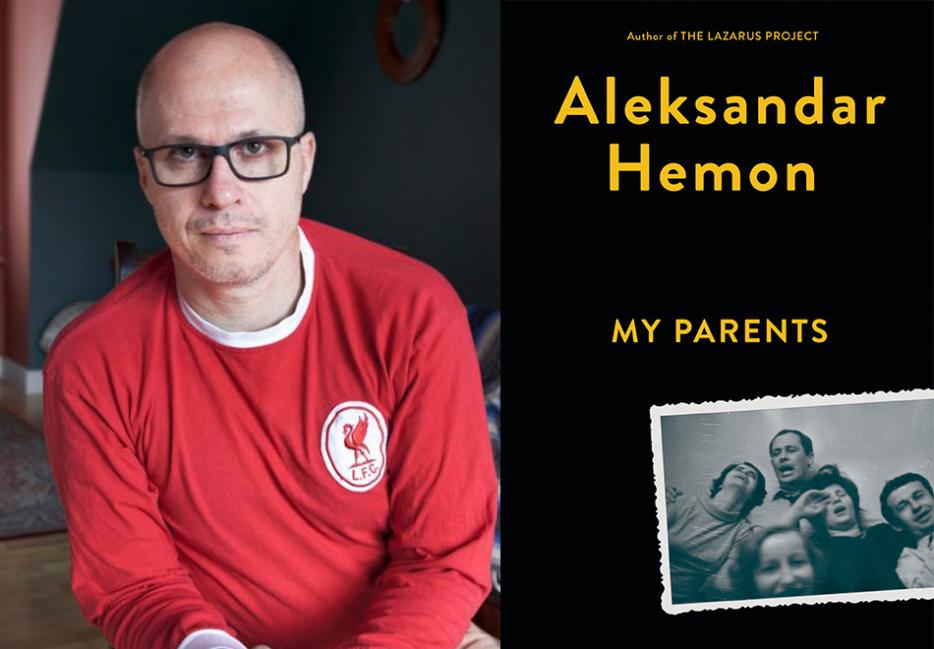

Before reading Aleksandar Hemon, I had a theory that the best way to write about the Balkans was through fiction. The region’s head-spinning politics and hard edge of suffering were elements too raw for the inflexible mode of non-fiction writing. Hemon’s work is one of the few exceptions. His writing—perhaps because his theories of fiction and non-fiction are more complex, or perhaps simply because he’s a master of the form—manages to wrangle the truth, taming it, making it comprehensible again.

Hemon’s most recent book, My Parents/This Does Not Belong To You (Hamish Hamilton), is actually two books in one, presented dos-à-dos, with a series of family photos separating them (or maybe connecting them) in the middle. On one side, the story of his parents' lives and their journey from Bosnia to Canada, and on the other, an impressionistic series of short chapters from Hemon’s childhood.

For anyone who has experienced displacement, Hemon’s writing is remarkable for its ability to describe the unbridgeable gap between homes past and present. Trauma, migration, and memory are approached with an expert’s hand and the garbled, terrifying voice of the past is made clear and lucid.

Hemon, who came to the United States from Yugoslavia in his twenties, and who still speaks with a deep-voiced Slavic lilt, has been compared to Nabokov for his sharp prose and his decision to adopt his second language as the language he writes in. But his work contains shades of Proust, too. He's able to capture the particular fine-grained texture of memory, its vivid moments and fuzzy edges. One of the first memories he describes in an early chapter of This Does Not Belong to You is the feeling of cold water being poured over his face after falling into a deep ditch filled with cow excrement.

At a reading in Toronto, the day before our interview, Hemon had small containers of honey available for attendees, produced in his father's backyard apiary in Hamilton. The day after the reading, we met at a cafe in Toronto.

Seila Rizvic: What is the process of actually translating a memory into a written work? How does that work? When you're writing My Parents, a more traditional memoir, do you have to be in a different mindset than when you're writing the fragments found in This Does Not Belong to You?

Aleksandar Hemon: I mean, I guess it's a memoir, but I don't think of it as a memoir because it's about my parents. But either way, whatever it is, it's about a shared past. There are shared points, shared references. That is, we remember certain things in our family life that my parents also remember, and that my sister also remembers. And there might be people outside of the books who remember. And then it's part of this history of the country and the place. Everyone remembers the war, except everyone has experienced it differently. But it's a referential event. And so, there's this field of shared experience and memory of my family and our life and then the vaster field.

Whereas the fragments, some of those things, I'm the only who would remember them. My mom remembers us coming back home after vacation. She says, “Yes, that's exactly how it was.” But no one remembers when I was drowning in shit.

Anyway, the point is, there's a certain creative aspect in retrieving memory, you have to complete blanks, and so the imagination kicks in. And that's my territory as a writer. But it also means that often, what you remember is the story of the memory. The memory is behind the screen of narrativization. You don't have direct access to it. The experience is contained in the narrative. However small.

So, the actual process of compiling the parents’ portion would have been more collaborative and actually talking it out with others, whereas the other ones would have been more instinctual?

I think non-fiction in general is kind of inherently collaborative. Because you have to verify reality, whatever it is. From journalism to memoir, because who can remember one's life without remembering other people? The moment you're remembering other people you have a responsibility toward other people and what they remember. My previous work of nonfiction, I had to run a lot of those things by my parents, by my sister, by my friends. "Do you remember this? Well what was that like?" Whereas, This Doesn't Belong To You and fiction, it's more closely in the domain of pure imagination, storytelling that cannot be verified. It liberates you in some ways from the need for verification, because other people are not involved.

Another way to put it is that everyone, including writers, everyone invents the story of their life. Not invents, rather, constructs a story of their life. Many real parts, some missing parts—you add to it. But you are the main character in the story of your life, which is both true and constructed. It's both authentic and artificial. It's both fictional and non-fictional. But the non-fictional part is verified by the others, they check you. However, there are parts—your interiority, or your sort of narrative of yourself—that you want to sustain. “I'm a decent person.” Which might not be true. But if I think that of myself, then I will construct a narrative of my life to support that proposition. Eliminate all the little stories where I was not a decent person.

There's a portion where you talk about the idea of truth and memory. You describe “a story I heard in Sarajevo from someone who had heard it from someone else, who, in turn, knew the person who knew the person to whom all this happened. In short, the story is as true as can be, even if I fact-checked none of it, because it accumulated relevant experiences and value while passing through other people.” I liked this description because it describes how, like in a work of fiction, something can be true without being necessarily based in facts or reality. It seems to me that memory can function in a similar way, where, even though a memory may be imperfect in terms of accuracy, the way that it accumulates value in transmission between people still holds an important meaning.

That would be closer to oral literature, right? So, if you are passing a story from one person to another, it passes through bodies and minds and passes through these narrative machines that each person is. Because we do narrativize our interiority, our lives, our selves. It's incomprehensible without narrativization. One doesn't have a sense of selfhood and continuity in one's life unless it is somehow [narrativized], unless I can conceptualize the story of my life.

So, to tell a story from one person to another to another, this is how, well, this is how the Iliad was assembled and all masterpieces of oral literature. But also, it aggregates, each time it passes from one person to another, it is vetted against the experience of the storyteller, and they adjust it—it stands to reason—they adjust it and reshape so as to make it fit into the experience of their life. So as to make it, as it were, enough about them so they can tell the story. I think in some ways this is basically how literature works. What do I have to do with the 19th-century Russian novel? It's an object that expands to me from other people, and I know that there are other people involved, and the field of literature that we share and these things pass.

And so that's a kind of truth that is not factual, what is and what isn't. Narrative or narration is an important tool for assembling reality and imagination. That is, we have to imagine something as real before it can be real.

I think there's an interesting paradox in storytelling and conversation. If you're telling a story it’s already artificial, right? So, it already blocks, to some extent, the access to the absolute truth, the actuality of it. Which is why memory is always both true and not entirely true. It can become true if it is fact-checked against other people. Were we sitting in Toronto on this day you and I, talking? If we never see each other again we might remember this entirely differently. I'm sure you experienced that. Remembering the same thing differently. "I never said that." "you were never there," "I didn't drink coffee, you drank a latte," you know, and all these things may differ. And if you remember individually, that can only be contained in a narrative that we tell ourselves and others. To make it real we have to compare our notes and come to a consensual set of facts. However, the truth of this conversation could be passed in that artificial narrative and transformed.

It's interesting that you mention fact-checking. As an actual journalistic process, it follows a defined set of rules. When I've worked as a fact checker for magazines, I've actually fact-checked fiction pieces, like short stories, as well. I imagine you've gone through this as well as a writer.

Yes, the New Yorker does that as well.

Yes, it's an interesting clash of "fact" and fiction. I get the sense that the fact-checking process, asking questions piecemeal, question by question, makes it very hard for sources to get a sense of the whole article. The piecemeal approach to fact-checking can't get across the same information as reading the final piece in its entirety would.

If you declare it as fiction, you agree to a different set of rules. A witness in the Hague, you want them to be as specific as possible and it then has to be checked against a number of other sources. So, there’s a legal value to the truthfulness of it. But the value of the factuality of fiction is very, very low comparatively speaking. It's never nil, but it’s very low. And it also depends on what the facts pertain to. The facts of genocide in Bosnia or the Holocaust—I'm not making this shit up, it's not within the domain of the freedom of the writer. So, I don't have an absolute answer or methodology to resolve this conflict. I think it's inherent in the very establishment of the difference between fact and fiction.

In Bosnian, in Slavic languages and a number of other languages for instance, the distinction between fiction and non-fiction in literature is non-existent. Or it's more complex. In translating my previous book of non-fiction into Bosnian with my translator, the only place where I used the words—"fiction," "non-fiction"—was in the acknowledgements. And she asked, “How do we translate it into Bosnian?” It was a huge problem. We were bending backwards and adding a paragraph, which you don't want to do in an acknowledgement. There are general differences between lies and truth, but not fiction and non-fiction as modes of narration in literary text. So, I cut out the acknowledgements, rather than explaining it.

But in Anglo-Saxon literature it’s taken to be self-evident, the difference and the concept. And then you run in to all these paradoxes and intentions that no one can quite resolve. For my work, what I care about, the overarching term that covers both fiction and non-fiction and sort of at least relieves the tension, is storytelling or narration. Narrative as a container for both of those aspects. The closest translation to non-fiction in Bosnian and other southern Slavic languages is "true stories," istinite priče, because that includes that narrative aspect. I think, by way of imagination and narration, we create structures that contain truth, general truth, and create a situation in which truth unfolds in narration. It does not preexist in the narrative project, but it unfolds. Or, if you wish—one discovers it.

You were talking a bit about oral history and also the shared experiences between you and your family and that shared memory component. Obviously, most families don't have someone who is a writer who will write a book that will be read by others about their family history. I'm wondering how those family stories change once they're actually written down and made available publicly. Does that change you and your family's relationship to the stories?

Yes, it does. I mean, for oral histories you have to have oral activities. People have to sit around and tell each other these stories. My parents' generation, particularly on my father's side, they still do it, they sit around and tell stories: "Do you remember? It was 1941..." The story on my father's side was the narrative of my migration. Where we came from, who's there.

One of my cousins also lives in Hamilton, he drew a family tree that reaches four generations. Beyond that, no one knows, because there are no documents, there are no written stories, there is only what has passed through us through all this. Every generation after mine and my cousins, my children's generation or maybe their children's generation, where will they get those stories? I could tell them, but the situation in which the whole family, or much of the family, sits around and tells those stories, is less and less available because of dispersement. If we all lived in the same place and saw each other frequently, because we live close enough, we could just sit around and tell stories, and we'd pass it down the line. But migration necessitates narration, and it also necessitates things being written down. So, it can be transacted.

My mother said, with a finger raised, which is an important point, she said, "This is a monument to us." I like that she said it, it's lovely. But monuments don't change. They don't adjust. It's a solid, unchanging thing that stands in time. Which is inescapable, but it's also sad. A monument is what you raise when people are no longer around. It's an object symbolizing the present.

Was there any hesitation on the part of your family when you first decided you wanted to write about them and your shared history?

No. For one thing, I've been writing about them for a long time, my parents, and they're always complicit. There's also nothing embarrassing or shameful or secret in our family history. It's all complicated, complex, adult life.

I remember when I was in my twenties, just before the war, I realized now we could be friends. When I was a child they were all over my ass, you know, to wear warm clothes, and study and all this, and then, somehow, I got out of that, and then we could sit around and talk about things. And then it was broken up because I moved there and they moved here, and we didn’t see each other for two years. But then once we were close enough again it was restored. We'd sit around and argue as adults.

And what I also did, which is something that children don't do with their parents, I listened to them. There are times, even as a grown up, where you argue with them. In the interview situation, I would ask them, and then I would listen. I would not try to correct them, I would not try to say, "No, you're wrong about that." "Tito was this" while they think Tito was that, I'd just say, “What do you think,” and they'd tell me what they thought. And it was nothing new, what they revealed to me, but it was a different dynamic.

That's sort of more of a journalistic process, of just letting them respond rather than debating.

Yeah, and it's also a more generous process. More forgiving. I mean we always loved each other, there was never any scandalous situation where we had to make up. But there's a certain amount of unforgiveness that comes with being close, knowing each other, remembering everything that we said to each other, ten, fifteen years ago, from a week ago. And all these, not quite grudges, but ongoing arguments, "See I told you, remember I told you seven years ago this was going to happen." Listening to them, I mean it's necessary for journalistic interviews. It's not for me to prove that I'm right and they're wrong. You just listen. And that was great, it was liberating. That in itself was worth working on the book.

You also discuss "catastrophe," or "katastrofa" as a theme in the book and as a literary term, synonymous with denouement. Catastrophe, you write, “allows for narrative escape. If you were lucky enough to have survived the catastrophic plot twist, you get to tell the story—you must tell the story.” Is this a factor for you when it comes to why you write?

It is. I was never under direct duress, my life was never in danger [during the war], so surviving is kind of conceptual. And then that transformation that comes from overcoming the obstacle, you can think of it as a narrative operation, right? To get from point A to point B, and between point A and point B is a significant obstacle, whatever it is. Getting a passport, citizenship, learning the language, whatever. When I teach creative writing I always encourage my students to think of the transformative possibilities in the storytelling. I want them to have something change.

So, this transformative event, you can think of it as a catastrophe. The initial set of conditions is undone and something changes. It's kind of theoretical, but the point is that, whatever it is—you live in Bosnia, war, and then you live in the United States or Canada— and life is different. Language is different, everything is different, door knobs are different. So how do you tell the story of the transformation?

Or rather, it's the other way around. If you go through this transformation, you have to tell the story. One feels, I feel, the need to tell the story. And so that means that catastrophe is the engine of transformation. And transformation, you can think of conceptually as migration, and that it's literally migration for people like us. To get from point A and point B and something happens in between. When you get to point B there may be people there who will listen to your story about what happened between point A and point B. Narration is migration squared. Migration necessitates narration.

In one chapter you describe singing “Sarajevo, My Love” on the bus during a school field trip. The lyrics you write in the book are translated from Bosnian to English. You write, “The memory of what happened on that bus is deposited behind the stained-glass pane of a foreign language. I will restore these verses into the original Bosnian, where it will be more present, but you will not be able to read it. This does not belong to you." I'm interested in whether writing in English, about events that took place in Bosnian, changes those memories somehow?

It's an interesting question. You can think of writing literature as documenting as closely to facts, whatever the facts are, as possible. And for that you have to believe that you can reduce or even avoid mediation and transformation that comes from it, that you can tell an absolutely true story. Whereas my position is that literature is a transformative aspect of that. The authentic memory is no longer available, in any language, it's always already transformed by the act of narration. There's an additional transformation in all of it existing in English.

Now one can think of it as the loss of authenticity and the loss of truth, an existential void, because nothing is real and true anymore, but to me, it is the transformative possibility of art and narration and language. That's what's great about literature. To read and to write is to engage in the processes of transformation which removes you from the original event, the original experience, but at the same time, it was never available. One might as well accept that fact.

But would you agree that there's something different in telling the same story in English versus in Bosnian?

Yeah, absolutely. I like this Robert Frost quote, "Poetry is what is lost in translation." A conservative, excellent, American poet who lived in the same fucking place his entire life. Only knew one language, only knew people who spoke that language. It was Brodsky who said, "Poetry is what is gained in translation." Brodsky was displaced, a Jewish person from Russia, who translated from Greek and English, and was not only a poet but a translator. And the thing is, both of them are right. You lose some, you gain some.

But to think that you could exactly translate from one language to another—if one were able to translate a poem from one language to another exactly, it would be the same language! If all the connotations of all the words, and all the implications, and all the contexts, were available in two languages, those languages would be the same languages. It cannot be that. The beautiful, enormous variety of human beings, is in fact contained in those transactions.

There's no literature without translation. Every time something is translated, something is lost and something is gained. And so, because the original experience is never available, there's no choice but to enter a transformative process. The question is, are you going to think it's a sort of existential, ontological defeat of selfhood, that you can never have access to the original event? Or do you think about it as a transformative operation that makes human civilization and literature possible? If we had ways to convey our original experiences, there would be no literature, there would be no need for literature.

Something that sort of struck me as I was reading, in many of your books actually, is it's possible to see how the story would have been written if it had been written in Bosnian. There's a certain cadence that's familiar to me in the form of Bosnian, oral, storytelling but then, translated into a written English form, it's still noticeable.

That's good. I think those are rhythms and cadences that I was acculturated to. People ask me often—you asked the same thing but more intelligently and more complicatedly—am I the same person in Bosnian and in English? Or do I change? And I am, and also I'm not. I am because, even if you only speak one language, you use different registers, different modes, you speak differently to your parents versus your friends.

In Bosnian, my range is from speaking like a Sarajevo thug, to speaking like a seemingly intelligent person who uses complex words and incorporates Croatian and Serbian idiom. And so, to be bilingual is to enjoy various aspects of yourself and your personality. Everyone is more than one person and more than one thing. But if you're bilingual or multilingual than you have various languages for those personalities, but all of them are yours. To me, I don't think of myself as different in different languages at all. I have the same sensibility. Of course, who am I to say. But I don't think I become someone else, or less Bosnian, if I speak English to you.

And what if you had never learned English? I've thought about this, if I had stayed in Bosnia and possibly never learned English, if I would be different somehow. And, of course, now my Bosnian has withered away somewhat, but I like the person that I'm able to be when I speak English.

The analogy that I like to use is that, in a two-dimensional system of representation, three-dimensional objects are reduced to two dimensions. And so, to a monolingual person, a multilingual mind is incomprehensible—it looks like a monolingual mind. People who speak one language, they cannot understand what it's like. Even if you don't speak it fluently, it's in there, it's the culture, your parents' voices, the whole thing, it's all there. The mind is shaped. And there's neurological studies that show that bilingual children's brains function differently in many ways. So that's a great advantage. But people who are monolingual, they ask me, because they cannot understand how that's possible, “Are you the same person?” Yes, I'm the same person, with an extra dimension. But the same mind. The more languages you speak, the more dimensions you have. It activates parts of you that may not be activated otherwise, and it forces you into modes of thinking in which you have to make multiple choices. I always know that there's another way to say the same thing.