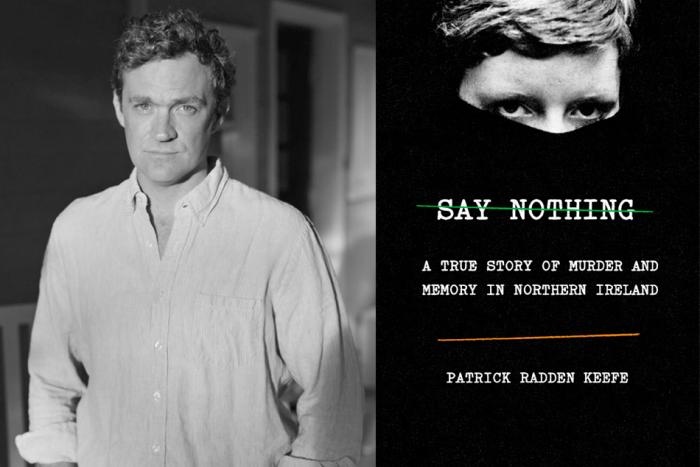

This week, Hazlitt's new publishing imprint, Strange Light, is launching its first two books. (Obviously, we have impeccable taste and these books are really good.) One of these new books is Lanny, a novel from English author Max Porter. Porter is the author of the genre-bending novel Grief Is the Thing With Feathers (winner of the International Dylan Thomas Prize and the Sunday Times/PFD Young Writer of the Year Award, and adapted into a sold-out stage production starring Cillian Murphy), and takes a similarly visceral approach to his new book.

Lanny takes place in a small unnamed village outside London, and the first half splits the narration between four wildly different characters: Jolie and Robert, recent transplants from the city and parents of the precocious Lanny; Pete, a revered but reclusive artist hired to give young Lanny art lessons; and Dead Papa Toothwort, a mysterious folkloric creature who listens to the nonstop chorus of voices from the village and takes particular interest in the titular character. Then, Lanny disappears, and the residents of the village are forced to confront what they know about themselves and each other.

Porter had just started his book tour last week when I interviewed him and spoke to me from his hotel room in New York City. He is an energetic and gregarious speaker, different than the impression his prose had left me with. I had called him on his British cell phone number given to me by his publicist.

Anna Fitzpatrick: I accidentally wrote down your number wrong and dialed Germany, twice.

Max Porter: Really? Were they nice Germans?

It was an answering machine, and I wasn't sure if it was yours.

It was me just doing my funny German answering call prank.

Just in character for this book tour. But not a character that anyone is familiar with.

I go off script.

So, congratulations on having one of the inaugural books out with Strange Light. I didn't know what it was about when I started reading and I didn't know it was going to be really scary, so thank you for that. I was house-sitting for a taxidermist and I was alone with all these dead animals.

Oh, shit. It's interesting you found it scary. What did you find scary about it? Papa Toothwort?

Yeah, the giant dead plant monster who maybe kidnapped a kid, and then [redacted for spoilers] and [redacted] and also [redacted]. Like, what part of it do you not find scary?

Okay, cool, yeah. I get that. I guess I've forgotten that because so much of the conversation I have around that book can't really include what happens at the end, and can't really include Toothwort, you know. I tend to talk about, when I'm doing events, I talk about family and myth and childhood and England and all this kind of stuff, and then I sometimes forget about part three [of the book]. Even just lying in bed because I couldn't sleep last night because I'm so jet-lagged, I was like, "Oh yeah. He does [redacted] in the [redacted]." [Laughs] Anyway, thanks for reading it.

I'm going to have to figure out how to transcribe this interview without giving away the ending.

Oh yeah, it's hard. The main one, the really hard one, when I talk about the book, because I want to talk about the kind of moral framework for the book, as well as some of the formal concerns of mine, it's really hard not to mention the ending, where you find out that Toothwort himself is [redacted]. That's really hard, because I desperately want people to discover that on their own. You simply can't talk about that in advance of reading it. But that explains so much about the book, about why he behaves the way he behaves.

It feels like a very subtle reveal. You have to be paying attention to get that.

I hope it's less of a reveal than a kind of clicking into place. It's almost like, in musical terms, a repetition of a refrain that you had heard somewhere before but you hadn't quite realized is an important refrain. Just like a coda or something.

Well, there are elements of horror and mystery to your novel, but it's not a whodunnit.

Well, we done it. We wielded it.

Ah, society done it. Once again.

And I hope that's sort of the point. The reveal is not a literary device or anything like that, and it doesn't really have anything to do with me as the author or any of the characters in the book. The reveal is an invitation for you to have done a certain amount of thinking throughout the book. It's to do with the relationship between book and reader, and it should kind of cast its light differently on everyone. That was my thinking about it, that your ending or understanding of him as a character, or even Lanny as a kind of an absence of a character, is very bespoke. It's yours. Hence some of the white space in the book, and some of the absence of things that you would expect to be in a novel. Even you talking about the scariness of it, or the horror, or the unease of it, that's, I hope, very unique to your encounter of it.

Photo Credit: Lucy Dickens

Talking about separating your art from the artist, that's kind of a theme in your book. Lanny's mother is a former actress turned crime novelist, and that kind of comes back to her when Lanny goes missing. People start dissecting the content of her book. That happens to some extent with Pete's artwork, where he's being interrogated about some of the adult subject matter of some his paintings in conjunction with the missing kid. Was that something you were trying to work with in this book?

To be honest, I didn't really think about it. I made them artistic people because I'm interested in those people and I felt that was relevant to the themes of the book. But I suppose—yeah, it's nice to have some clarity on that, from your question. I suppose one of the big issues of our time is how to separate the art from the artist and what to do about bad people who make great art. These are pressing questions. But, to me they are questions that come from the artificiality of the role of the artist. I think we put the artist on too much of a pedestal anyway, so the question of whether we should care whether they were bad is sort of like, "Didn't you know they were bad anyway? Why did you think they were special?" Why in the culture industry did we need to elevate them onto pedestals, pretending they were perfect? None of us are perfect, and artists tend to be more flawed. So, it seems laughable to me to discover that these men are all creeps, because of course they were. Didn't you read the work?

So, I'm interested in that, but one of the things I'm worried about now is that art becomes a more rarefied thing and becomes only defined by its cultural worth or its place within the cultural system, but art is deeper than that. Literature is the common language, and in the same way art has a deep and important role in our society more than just pretty things in galleries to be sold. What I wanted to do with Pete particularly was to create someone truer to that, and I wanted to show how society has been unkind to those people, has othered them. I wanted the artist as threat to be explored around Pete. I didn't need to specify too much about the kind of work he made, but it kind of made sense that the kind of work he made was accepted in an avant garde context, but then becomes utterly terrifying to people in a localized, social context, where the apparatus of understanding is less developed. The classic thing of, what sense does someone like Louise Bourgeois make in a psychoanalytic context, or a context of art theory or surrealism or the New York art scene of the 1970s, and what context would that work make in a French farmhouse when someone who isn't in that world is confronted by those themes? That's always been a fascinating theme to me.

But more than thinking about if artists are just good people or not, I was thinking about the ways art is viewed as autobiographical, even when it's not. I know that's a response your own work has gotten a lot.

That's why I made Jolie a writer. I was kind of yelping against a particular current in UK literary culture, which has upset me in recent years. Anti-intellectualism and misogyny go hand in hand to block the work of fiction writers, particularly when they're women, to write about lives other than their own, or to write well about their own life in the context of fiction. You have it in your own literary culture I'm sure, but it is dismaying to watch the way we don't allow women to be novelists and clobber them around the head with the kind of biographical fallacy. It happens everywhere, but it upsets me in the UK when there have been books that I’ve greatly admired either as a publisher or a reader, and then see them reviewed as if they're autobiography. I wanted to set her up as a little case study of that, but I realized I didn't need to get bogged down in the type of work she makes, or even the type of person she is. You can do that kind of deftly with that one kind of tabloid thing where it's like, let's look at the woman who writes this work, behind the mask as it were. I see that as the manifestation of the whole critical impasse anyway, that kind of moralistic judgement.

I saw Sally Rooney interviewed at the Toronto Public Library a few weeks ago, and she was saying that she purposely tries to abstain from revealing too much about her personal life, and that she feels like she's disappointing people when she reveals that her books aren't based on true stories, and that she just makes them all up.

Even still, there will be this desperate desire for personal information, an, "Oh yes, someone found out Sally Rooney lives with her partner who is a teacher, he must be Connell." Or Sally Rooney must be writing for him or around him. The desperation to do that is an astonishing thing in 2019, X many years after postmodernism, a hundred years since Virginia Woolf. It's quite extraordinary that fixation, almost fetishization, of the biography, is still so powerful in literary culture. And how boring, of all the things you could talk about with Sally's works, that that is a thing that people want to talk about. It's sort of crushing. It's a way to kill the possibilities of the form as well. The novel should be one of our most radical forms but you'd never guess from a lot of literary engagement.

So, my next question is, are you Lanny?

Who stole me? [Laughs]

Besides society, of course.

God, I've never thought about that. I did get stolen!

From who!

It's not funny. I've never thought about this. These questions are really unlocking me. I got stolen at the Oxford Covered Market when I was about eight or nine years old, yeah. I was just chewing my jumper, not really paying attention, and this guy just led me away.

Did you get... put back? Are you okay?

I suddenly looked up and started to go, "Oh, uh, er, help..." and my mom came barrelling around the corner, swinging her handbag like an ax and knocked this guy around the head. I don't think he was actually a predator or anything like that, I think he was a kind of confused drunk or something.

Was he made of plants?

Yeah, and he was shapeshifting.

Lanny is the title character, but like you said, there's this space in the book. For the first part of it, you have four narrators, including Toothwort himself, but you never hear from Lanny directly.

It's one of my preoccupations—I tried it in my first book and I'm going to try it again—but I'm only interested in how accomplished readers are at building characters beyond the writer's determination of them. I remember being really sorely disappointed as a child when a character was overly illustrated, or when exposition was just heaped onto a character in a way that removed the imaginative possibilities for me. Lanny does say a few things, and there is some dialogue, but not very much. I want the book to be a series of mirrors, and Lanny exists as a reflection of other people's idea of him. To Robert he's a kind of reprimand and in some respects a threat or emblem of disapproval, and to Jolie he's a kind of muse, and there's a lot of maternal and almost erotic obsession with the surface of him, and him as a kind of projection and site of trauma for her. Same with Pete and their friendship, which becomes a kind of natural thing but becomes loaded up with societal suspicion. I didn't need to write him, I just needed to create him as accurately as I could in absentia through other people's consideration of him.

There were a few times when he did appear a bit more, and I realized the damage I was doing to the book as a warp and weft of ambiguity. There's a textural thing made up of other people. I did great damage to him when I put him in any great detail. There was a bit where he had a long conversation with Pete about sexuality, and I realized I was removing all possible hint and suggestion and interest for the reader to gauge their own sense of Pete as a sexual person. More happens when I took stuff out. I find that really, really, really, really pleasing to do, realizing how much the reader can do if you just give them a bit. Same in the second part. You know you can get to a person, both a character and a role within a community, and their kind of whatever, psychosexual or socioeconomic type. You can do that in just half a line. You just set them up deftly in relation to other things. It's not what they are on their own, it's how they're responding organically to other things in their ecosystem. Same with Lanny. I limit him. I make him smaller for the reader, the more I tell you about him, where I want him big. I want him up in there floating.

Also, for me as a writer, he was the one character I didn't do any work on. I didn't imagine him at all. I don't have a vision of him in my head, whereas everyone else I have a hyperrealistic sense of. I know what Robert looks like naked, I know how he eats, I know how he chews, I know how he blows his nose, I know his sexual predilections, everything about those characters. Whereas Lanny just needed to remain for me an absence as well.

I don't remember reading if you even gave Lanny an age.

No, I didn't. You don't need to know. I have a sense of how old he is. He can't really be teenage, and some of the things he does and some of the intellectual currents he's surfing on with the adult world means he can't really be much younger than the certain age, but yeah, I never name it. Same as I never really need to name where the place is. There's so much I don't need to tell you, which is the point for me.

It's something the characters do to each other, especially in the latter half of the book. They fill in the blanks when they have their suspicions with each other, particularly when it comes to Pete but also between Jolie and her neighbour, Peggy.

The point of having the kind of floating village voice which is sound rather than literature, one of the reasons is to train the reader in a way of kind of half listening, half reading, where they're not reading it as if it's normal literature. They're kind of floating over it, picking up traces and scents of things, so later on things prickle or echo or reverberate according to that texture, and so that's what I want you to be doing. I want you suddenly like, "God, had I completely abdicated my responsibilities? Why was I as a reader not alarmed that Pete was spending time with this kid? What kind of person did I think Robert was?" A bit more like a musical experience, I want you to be like, “He taught me how to play this music in part one,” and that “my notes are sounding in some of the stuff that the village is saying.”

Even if some of them are kind of unsubtle. Obviously, Mrs. Larton is unsubtle and obviously I'm talking about a particular type of person, the moral judgement of a particularly religious person or the vicious gossip of a more unpleasant person in the village, but I hope they're not caricatures. I hope they reflect realistically and truthfully the way all of our minds work, even the things we don't say that become personally taboo. As if we're all moving around in microclimates of our own taboos, our own questioning of what is an inappropriate thing to think or say. The village is not just a model of individual consciousness, but also off of how our relationships work. Things you'd say to your partner that you wouldn't say to a stranger, and things that a community says to itself that it wouldn't say to its newspaper, and vice versa. It becomes a map of an individual relationship, and so a small place, and then a big place, and then I hope also of like a nation state. This is how countries think. This is how we write history. This is how we contextualize our past and so on and so forth. For that to work as I want it to work in a reader's head, so much of it has to be white space.

You compare it to music, but it's a story so suited to the form of a novel. Just from the way you literally place the words on the page, to what you choose to reveal or not. You said you had a similar approach to the last book, but you adapted that to the stage. I'm wondering how your storytelling technique changes in a visual medium like the theatre.

The thing about Enda Walsh who made the play is, he's a very, very visual theatre maker, and he's very collaborative. He chose to make Grief an assault on the senses. He wanted to make the book come to life in the most vivid way possible. He realized to do that, he had to focus on the wordiness of it. It's not like that guy's obsession is, you know, Chuck Berry. That guy's obsession is poetry. His trauma manifests itself through literary jokes, literary devices. The play is really, there's words dripping off the back of the stage, there's huge words scraped in the thing, typewriters come alive, bits of paper are all over the thing, the dad is always drawing stuff and always saying, "ah, look at this drawing I've done," or, "I'm writing this note." For me, the visual I had in my head writing it became very literalized on stage as words. I guess that wouldn't happen again. That was completely unique to Grief Is the Thing with Feathers. There is always a death, because with both books I talk about the ambiguity and wanting interpretive doors left open. With Grief Is the Thing with Feathers I wanted no door to be closed. So like, the idea of the crow being a metaphor, or the crow being a manifestation of the dad's obsession with Ted Hughes, or it being a joke, or it being a real crow, or it being the children's fantasy of a crow, I want them to all be possible. I once read a review, and I mean I've gotten horrible reviews and stupid reviews and all sorts of things, but the saddest review I ever got just said, "Okay, I get it, the bird's a metaphor for death." I was like, "Oh no, please don't do that!" [laughs] "You just shut all the doors. What a shame. What a shame for you, and what a shame for the boys, and what a shame for the dad, and what a shame for the bird."

Where was this review?

It was a famous person I shan't name on Twitter. And, fine, to each their own. Totally fine. I just felt that will be a pity for them, because there's so much colour and noise outside of that interpretation. But anyway, the theatre obviously has to make choices, and he chose to make crow and dad the same person. It's an astonishing thing, it allows for a really truly virtuoso performance. Cillian Murphy is like, I've never seen anything like it. It's a performance I'll never forget as long as I live. But it nevertheless closes down other interpretive avenues on the stage. You have to do that. The stage has power literature can't have, and literature has power that the stage can't have, and one of those powers for me is the openness.

I want to close with a softball. What is the role literature in today's society?

[laughs] What is the role of our literature in our society?

Or just, art in general. What's the point of art.

I was just in Sydney with lots of amazing writers, but one of them was George Saunders, who was reading my books. It's amazing to meet someone you admire as much as I admire him, and him be reading my work, ‘cause it kind of charges the conversation in an unusual way, especially when there's a kind of, you know, mentorship or admiration thing going on. Like, I'm on my knees, admiring George Saunders.

Lincoln in the Bardo is a book I thought in some ways parallels yours. There's the missing or dead boy, and the chorus of voices. They're loose parallels, but it was a comparison I held in my mind when reading.

I love Lincoln in the Bardo. I'm obviously massively flattered by the comparison. I do remember when I was first reading Lincoln in the Bardo I was thinking, finally, here's the book I want to read. Finally, here's a ghost story that is a love story. That is sort of the meaning of literature to me, how to connect us to each other and to our past. For me, the best books are the ones that teach us to mourn better, to refine and revitalize and interrogate the ways in which we relate to each other, now when we're alive and after we've died and before we've been born. Squash the space time continuum. I'm relatively unapologetically old-fashioned about the idea of the novel as an empathy machine.

I do think that is the case, even if that's too cozy a formulation. I read an incredibly intelligent article recently by Namwali Serpell about how that now clichéd idea of the novel is too easy. It lets us off the hook. Because we can say, "Oh, I've read books about that, so I care." And that's not real care. In fact, that might be part of a terrible Western failure to act, because we're busy looking at art that makes us care. I’m probably paraphrasing her terribly.

It's a charged question, right? I see a controversy bubbling this morning on the internet about this boat that's being exhibited at the Venice Biennale, a boat in which a bunch of migrants died. Whether you think that's good work or bad work, the work is asking the question. I guess personally, literature is about a way to worry and a way to think more carefully, and a way to express fear and love, but for all of us generally I think it should be the great question machine. If we stop asking questions as a society we become lazy and we become formulaic and we become obedient. Literature is just the way to dismantle, to ask back all the important things.

Anyway, to bring it back to George Saunders. He called it, the idea that it's small entertainment for a bunch of verified people, we cannot allow that to be the case. It must be the lifeblood of our society, for everyone and relevant to everyone and being written by and for everyone. I uncomplicatedly agree with that.