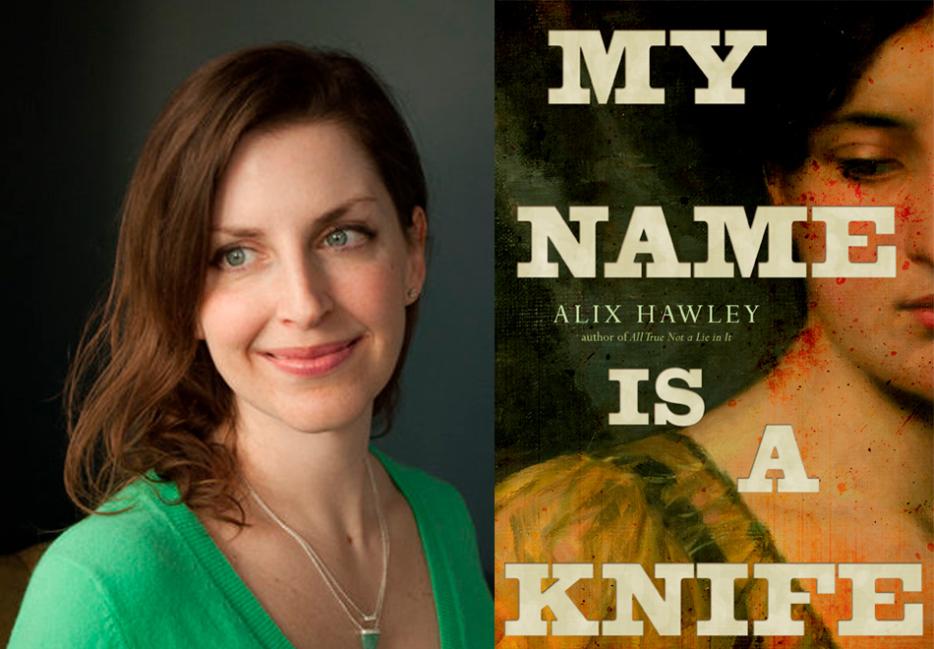

The mythology of someone like Daniel Boone, in the wrong hands, could be just another settler-saviour narrative, another white-guy-does-the-West fable in an American history already bloated with them. But in the hands of author Alix Hawley, Boone is tenderly broken open to get at what’s past the lore—he’s myth-busted.

In her 2015 novel, All True Not a Lie in It, Hawley shifted away from the classic chronology of the Boone story by choosing to zero in on some of the most painful and humanizing parts of his early life, and in doing so stripped him, quite naturally, of his cinematic trappings. Her new follow-up to that book, My Name Is A Knife (Vintage Canada), picks up at the same speedy clip, dropping the reader right back into Boone’s life as he steals himself out of a Shawnee camp and makes his way back to the fort and settlement bearing his name, now abandoned by his family and filled with a handful of hateful and rough settlers who think him a deserter. He fucks up—frequently and in ways that intensify his hardships. But by rendering Boone as fallible, Hawley makes it that much easier for the reader to enter an era typically illustrated in historical fiction with a heavy hand by authors more interested in the "heroes" who tamed it.

Here, the narrative is split between Boone and his wife, Rebecca, whose portion offers a more nuanced perspective of a husband as a kind of bumbling spectre, risen from the dead to return to a family who have had to move on out of the necessity of frontier survival. As Rebecca comes to make peace with the man who staggers back into her life and throws a wrench in her new-found autonomy, she also fills the new shape of their days: with children—hers and her children’s children, delivered by her hands—and with doubt, of the survival of everything that’s been created.

Knife is a hard book, with no clear protagonists. Hawley does little to tinge the time period with the golden tones of nation-making usually ascribed to it. But by letting each of her characters step between worlds, there are flashes of dark comedy and tenderness that come with living life in tumultuous times that seem, unfortunately, especially relatable.

Katie Heindl: You handle Boone so humanely, and by that, I mean, just like a regular guy. He is unaware of, or deflects, his own myth. Daniel always seems a bit surprised that anyone is interested in what he's doing, even Rebecca, only really comfortable in the eyes of his children. There might be an innocence to it if he didn't always reengage in ruinous behaviour. Was it critical to write Boone this way, a person as they might be as the myth was made around them, or did you want to intentionally ground him?

Alix Hawley: I'm glad he comes across as a human! And that's a perceptive thought about him and the children. You've got me thinking about that now; he is most comfortable with them, and with kids generally, including the ones in the Shawnee town, although he also feels he's failing them all somehow, whether as provider or protector. My guess is that his own childhood was messy, given the fact that his family was kicked out of their Quaker community, and so he wants to give them more than he had. Paging Dr. Freud.

Seriously, though, the historical material suggests he was a magnetic personality from a young age. I can only guess that's true, given the spread of his fame during his lifetime. He was certainly a natural leader, and even worked in government for a while, which I slide over a little in the book. I was interested in celebrity, and which people get it, and how fame metastasizes. And why we need that kind of heroic figure, which has of course been going on forever (I just read Madeline Miller's The Song of Achilles, a great novel about that need). But rather than having a deliberate sense of grounding, my greatest interest was always psychological. My usual question is: What would it feel like to be this person? (Not "What would it feel like if I were this person," which I've seen a lot of students get tangled up in. It's hard not to!)

What would it feel like to be this man? I wanted to dig into what that kind of fame would do to someone who really was a regular guy in most ways. Where Achilles and co. are puppeteered by the gods, Dan gets no divine intervention, however much he wonders about what cards Fate laid out for him. A lot of what he does, he does himself.

I found myself getting annoyed with Boone in this book, due in part to seeing him through Rebecca's eyes. The choice to add her as a narrator feels essential in this novel, which is almost sparser, less languid than All True. Was adding Rebecca's voice something you had planned for the sequel, or did she insert herself for you when you were writing this book another way?

Writing All True, I was half in love with the character Dan, and half wanting to slap him. I also loved writing Rebecca's parts; she was a brief but powerful presence in that book. I've always been interested in charismatic and unreadable people (and probably need therapy). When I thought about a follow-up, I didn't want it to be just a continuation. I wanted this book to stand on its own, without the reader necessarily having to have read All True first. And in a writerly way, I think every book needs its own problem to work out. Dan's voice took a long time to find—I drafted the first book in the wrong voice, twice—and I felt I finally had him in my bones when I decided to write this novel. So, Rebecca became the problem. What would it feel like to be married to someone like that, and to feel left by him, not knowing whether he was dead or alive, and to want to leave him as well?

Even more, what would it feel like to be her, this exact person, and how would she sound? I figured she'd be easier to write, being a woman and a mother like me. That was a dumb thought, as I don't usually write directly about myself anyway. And she was elusive. My early drafts of her narrative were in third person, which only made her even more distant. I wanted her to walk and talk on her own. In the end, her sketchiness in the historical record, and my uncertainty about her, became part of her character. She's someone who lives deep inside herself, keeps her own counsel, never gives much away, wields her power quietly. Writing the voice of someone like that is very hard! She doesn't always admit her desires to herself. She speaks much more sparingly and concretely than Dan, who flings similes around, and whose narrative sections are full of action. It was good to have his voice as a foil, actually.

And I got annoyed with him too, and I'm glad you did. Though I still love him, even his blindnesses. I think Rebecca does too. And I love her for her failures also.

How close to Boone's life did you keep the chronology? Was it as expansive to write All True and Knife as it feels as a reader to be moving through them? There is always a sense of more, or doubling back, but the promise of momentum regardless—did you make yourself stick to certain timelines and give yourself free rein for filling in the rest?

I think the best fiction about the past grows out of gaps, the things we want to know more about, the details and answers that are lost. So, I looked for those holes during the first research, then cut myself off from further reading, forcing myself to fill in character and motivation on my own. (I went back later to check details and dates.) I do try to stick to the general truth of events and chronology, at least of what's known of them. With this book, I did have a stronger sense of momentum, probably because the time frame is much more compressed—where All True covers decades, the majority of Knife covers just a few years, including a single week, the siege, in detail.

I did have room, though, to be deeply inside two different characters' heads, and to see each one through the other's eyes. I also had freedom to fill in quite a different Dan in this book, one who's caused a lot of damage and been broken himself. This time I missed the closeness to the Indigenous characters, like Black Fish and Pompey, the "black Shawnee," whom Dan has left behind. Writing the scenes when they meet again here was pretty emotional, because of the personal repercussions for all of them, but also because they represent the greater fracture between the Indigenous and settler groups in the book, who'd seemed very briefly, in this case, to have a chance of making things better, however illusory that was.

With All True Not a Lie In It, the title set the stage for even the casual Daniel Boone fan to understand it would be a novel that would put the reader behind the coonskin curtain, so to speak, and work a little bit to expose him. There's humour in it, there's reference to the tall tales and disconnecting accounts of this man's life while also being incredibly earnest, as if to say this will be the real story. My Name Is a Knife is stark and more subtle, because the story doesn't revolve solely around Daniel. Can you tell me about the title, why you chose it, and how you'd like it to set up this book?

Oh, God, this title cost me a few months of my life. All True Not a Lie In It comes from something Dan is purported to have said about a fake autobiography someone published in his name. That one leapt at me partway through an early draft, not least because we have so little in his own words (and they may not even be his words, but they fit my sense of him as someone funny and self-deprecating about his bizarrely swollen reputation—this guy from the eighteenth-century backwoods!). So, I liked the wink as well as the sincerity you note. Incidentally, I wasn't a fan, even a casual one, when I started writing. I didn't know anything about him. I was just hooked by the idea of early celebrity, and the way Dan and Rebecca lost their first child, James.

This time, the title was really hard to come by. I wanted something else in Dan's words, but nothing felt right. There's literally nothing left in Rebecca's words—she doesn't seem to have been able to write, but might have been able to read—so that didn't work either. I tried other sources from that time, as well as Dan's favourite book, Gulliver's Travels, but everything sounded stiff or too olde-timey, which I have a horror of. I want this book to work now, and not just be an attempt at ventriloquizing past voices. So much of what it's about is still going on. (Here endeth her sermon on how historical fiction is really just fiction.)

The main problem became finding a title that yoked Dan's and Rebecca's narratives. So, I had to make it up. (The file name was the cardboardish DB2 for a long time.) I played around with a few versions that included knives, probably as an image of the severing of the marriage, the settler-Indigenous relations, and both characters' internal fights (and also because—knives). Early in the book, Dan says that when he returns from the Shawnee town, hearing his old name, his white name, hurts him. Rebecca later mentions disliking her own name, not wanting her daughters to name their children for her. So, My Name Is a Knife popped up in the end. I hope it makes you want to pick it up, and keeps you thinking when you finish it (please finish it).

I need to thank my writing group partners, Corinna Chong and Adam Lewis Schroeder, for putting up with my dozens of "THIS IS THE RIGHT TITLE" midnight messages, and for trying with all their hearts to find the perfect version themselves. And my editor, Anne Collins, for finally saying, during her final manuscript run-through, "No, this is it, this is the title, stop."

The choice to end the book from Rebecca's perspective feels intentional to the treatment of the Boone legend, overall. This way, we aren't given Daniel's conclusions or future intentions, nor do we really get a full circle on whether or not he's found peace. Were there other reasons for handing the narrative over to Rebecca?

Real writer talk—I didn't want to write the death of either character! Having finally put together this version of Rebecca, I didn't want to end the book with her end (and she died before Dan). And because this novel ended up being so much about their struggle to work out whether or not to stay together, I didn't want to see Dan on his own in his last years. And I'm not sure he deserves to find complete peace, either.

I like that it ends with her voice, her observations of him, because she sees him better than anyone, except maybe Black Fish. But, also, because she's angry and damaged herself, and has had to find some reason to keep going. The upswell of the #MeToo movement while I was editing this novel made me see just how furious she is about the whole system. She may not be the most self-aware person, but I'd argue that Dan is even less, in spite of all his introspection and musing about what he's done. A lot of novels are about women thoroughly observing men who carry on unaware (Jane Eyre is the classic example). I'm certainly aware of that tradition. I think I hoped to turn it a little with the way this book begins and ends. A very small wrench in the works.

Reading All True and now Knife, it's hard to be oblivious to the Indigenous-settler dynamic at what was, essentially, the violent beginning of colonialism. Boone's relationship with the Shawnee is close, familial, but also damaging, paternalistic and violent. And there are tribal hierarchies based on familiarity versus the unknown—for example, a real fear of the Cherokee in Boone and his family. At the same time, even if we don't see Black Fish and some of the other Indigenous characters as much in this book, you treat their appearances evenly and with the same weight, even the memories of them. How difficult was writing the Indigenous characters in both of these novels given the current prejudicial climate Indigenous people face in Canada and the United States, and that their histories have likely been lost or not as fully recorded to the same extent as men like Boone?

It was difficult for me as a white descendant of Canadian settlers to even begin to write about the Indigenous people in the novels. And you're of course right about the fact that any recording of Woodland Nations histories at the time was done by settlers, usually with little benevolence (there's a mention of how the "Indians" always start their meetings with a long talk, which wasn't recognized as oral history). The lack in the record was worse than Rebecca's—so much was lost or misshapen or deliberately thrown away. And I was conscious all the time that because the point of view in my books is Dan's and Rebecca's, every presentation of the Indigenous characters is via white perceptions. Historians usually say Dan appreciated the Woodland way of life more than most Europeans—and part of his fame was as a "White Indian”—but so much of that was a takeover, in spite of his genuine ties to Black Fish and some of the other people he knew well.

I had a few known hooks to hang onto with Black Fish's character—he wasn't much older than Dan, he'd also lost a son, he was a powerful leader with a great speaking voice. But he couldn't just be Dan's mirror. I hoped to show him more broadly in his skilled handling of meetings and votes, and more in his relationships with his own family, his wife and daughters. When I'd gathered what I could from research, I wanted to show life in Chillicothe as almost mundane, people going about their business, kids playing, teenagers sulking, etc. I hope very much that it doesn't read as tourist-like, despite coming through Dan's perception. He becomes comfortable there, but he is a romanticizer, and once he's left the Shawnee, his memories are sometimes idealized. I was conscious of that too.

Black Fish's retreats into silence, like those of Pompey, the "Black Shawnee" and interpreter, became part of his personality for me, reflecting his knowledge that he won't get complete truth or fair dealing from Dan's people. And all the failed communication and misunderstandings, especially those leading to the siege, were heartbreaking to read and write about. Again, I had a strong sense of hopes for peace and connection raised and smashed, over and over. I read somewhere that it's easy to forget, when writing about actual events, that the people at the time didn't know what was going to happen. As silly as that might sound, it helped me keep up the sense of tension, from a writerly perspective.

The Cherokee Jim (his actual name is unknown) was the most difficult for me to write. He was a frequent visitor at the Boones' place before they headed towards Kentucky, and he was one of the murderers of their son Jamesie. The Ndé scholar Margo Tamez was kind enough to speak about him at a reading I gave, saying he was the strongest character for her, and the most sympathetic. I hadn't seen him that way, though I'd understood his action as a warning to Dan's party to stay off unceded land, as they'd been told. He returns in My Name Is a Knife at the darkest level of Dan's mind—Rebecca's too, when she lets herself think about him—and becomes a focus of rage. The way he's dehumanized becomes a symbol of the settlers' flattened image of "Indians." But he's not that simple either. No person is.

Babies. There are so many of them! I really liked how each birth added to Rebecca's agency, even her own and not the ones she delivered. Did you intend for them to be a subtle way to notch the passing of time, which in this novel can feel jolting from one big fight to the next, or as something to break up the carnage, or both? Because sometimes I have to admit, my thoughts were, "This does not seem practical."

Ha! Completely impractical, but true. There are so many historical babies—Dan and Rebecca came from big families, and had nine children themselves, who started producing their own kids very young—and that's one of the points both the protagonists make, that kids are having kids, all part of the general chaos of the time and place. I actually had to cut out some of the extended offspring, for clarity's sake (doesn't help when everyone has the same name). I did want the births to be Rebecca's territory as a midwife, and also to echo some of the children Dan knew in Chillicothe, the Shawnee town, especially the ones he can't forget.

You're right, there's a lot of tension and big fights in Dan's world, and I knew Rebecca's sphere had to feel equally urgent, though her life was ostensibly much more domestic, with all the "smallness" that implies. But what's more dramatic than childbirth? Frontier childbirth, without anaesthetic or forceps or stitches? Having been through two emergency caesarians, I'm always stunned that so many of the women and children around Rebecca survived and were healthy. Her narrative is as much about survival as Dan's is.

As for time, I wasn't very conscious about marking its passage—more with trying to keep both the tension and the events of both worlds lined up. A spreadsheet might have helped, but I'm Excel-impaired. Though so was everyone on the frontier, I guess. Verisimilitude.

The vernacular and dialogue between characters is so completely consuming, natural and of a time that it easily pulls the reader right into what could seem an otherwise daunting and antiquated world, stiff and not easy to slip into. It's clear you lived with these characters in your head for a long, long time. How was it to share your head with frontiersmen and women, for so long? Do you still?

Well, I was teary but satisfied to send them on their way with that final manuscript. And I can still tune in to Dan FM pretty easily; when a reader asks me what he would say or do in some situation, I usually have a quick answer. I can hear Rebecca more quietly. Both voices took a long time to get right, but once they were there, they were there. I think about them still, as well as some of their children—Jemima and James and Israel—and Black Fish, Captain Will, Pompey, Methoataske. They can hang around; I don't mind sharing head space most of the time (I have two young children—parents, you feel me?).

I'm drafting another novel now, set in a different place and time, and the main character slammed right into me. So, I thought I had that voice from the start, but it's shifting too as the mess of the draft grows. I still seem to expect instant gratification. I wouldn't have survived very long on the frontier, clearly.