Jenny Zhang’s descriptions of bodies are grotesque and explicit: they are often insomnia ridden, resplendent with open wounds, flinging off roaches with a dancer’s grace, sweaty and fumbling from childish and codependent explorations into sex and humiliation. Her characters are not written as heroes, or villains, they do not conclude their arcs with epiphanies about rising above their struggles. They are realistic and complex and artful. They are painful and sometimes kind; you can see the flaws they as narrators try to hide and it does not endear you to them but it does make them more interesting.

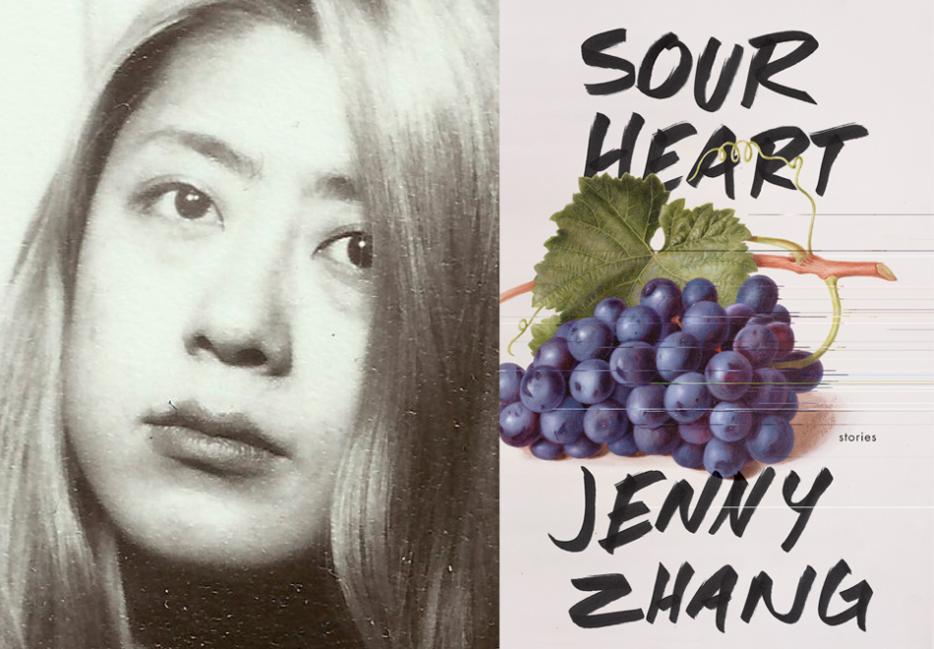

Her debut short fiction book, Sour Heart (Lenny), is a collection of stories of Chinese American girls who have grown up in poverty and have been raised through all the filth and intense love and fear it often contains. It’s a beautiful portrayal of the complexities and limitations of empathy, of family, of the lessons history can bestow through pain. Each character, all first generation Chinese girls who live in New York, is loosely connected. Many of them live, briefly, in the same shithole Washington Heights apartment side by side on dirty mattresses on the floor.

Reading this book made me physically uncomfortable at times; it stares at the physicality of poverty in a culture that has tried to deny the possibility of failure at all, and it does so unapologetically. Sour Heart holds space for the failure and shame that immigrant narratives often fail to explore with nuance; Zhang’s characters see and sometimes benefit from the upwards mobility narrative we’ve all been taught and spurn it rather than try to fulfill their expected role.

Jenny Zhang and I only see each other in summertime, and usually only over dumplings and complaints about our lives. The last time we hung out was in Jing Fong, a Chinatown restaurant the size of a football field. It is in Jing Fong that we met again, for this interview, a little less than a year after she read to a small group of our friends a sample from one of Sour Heart’s first chapters.

Arabelle Sicardi: You wrote this awhile ago by now. It must feel like a different baby than what you remember.

Jenny Zhang: It’s really embarrassing to go back and judge the person you were nineteen to twenty-one. I was nineteen to twenty-five when I wrote these stories. I think that because I never was able to get an agent from these stories, because I didn’t have any immediate success out of grad school, I didn’t have any of those markers of validations you’re supposed to get when you’ve done well. I don’t want to overplay and say I just got completely discouraged, but I got a lot of discouragement and some key encouragement. It created this thing in me where—you know how when you get rejected, your personality kind of calcifies in response to the rejection?

If I stay perfectly still, they won’t notice how sad I am.

Yes, and you take up the thing you were rejected for and it becomes a personal crusade? Like, “You said that I wrote things too long, too real, too unruly…” It’s not what people want out of immigrant stories, because they’re not really about a repressed woman, the woman who can’t emote or be angry. I wasn’t fitting in. So I doubled down. “I’ll be more disgusting, more gross, never write a novel, I’m going to make all my protagonists Chinese American girls because you said they limited me, so I will write every single kind of story and always use the exact same protagonist.” That’s what happened. That period was like, another period of editing. I’m using editing in the most broad sense, I was editing my soul. Editing who I was as a person. I don’t know if you do this, but not just editing the words on the page, I was taking feedback and asking myself after the anger: Am I limited, am I only writing about one thing? Do I need to write a novel? Do I have no concept of plot?

I don’t think plot has to be the best thing about a story, anyway.

I don’t think so either. Plot is just one variable to measure the value of writing. Some books have amazing plot and terrible language. Some have zero emotional intelligence, but are full of interesting ideas. Anything can be of value and plot is just one thing we value. I edited these stories each time I got rejected, and then at some point I just stopped working on them. I was writing nonfiction, and then when I published that BuzzFeed essay that went viral about literary yellow face, that was the first time I got a lot of attention from agents who wanted to represent me.

And can I ask, were the majority of them white?

It was mostly white and maybe one non-white person. Mostly white and almost all of them asked if I had ever thought about writing a memoir. Isn’t that the trap of the theory of the young girl?

Everyone wants us to have memoirs by the time we’re twenty four. Why won’t they take our fiction? Why are our imaginations not interesting enough?

And maybe this is crude to talk about, it’s not even that I don’t want to write a memoir. Beyond that, do you understand how vulnerable it makes someone to call something nonfiction? Not just emotionally vulnerable but financially vulnerable, do you realize someone that makes $40,000 a year cannot be hit by a lawsuit by some angry ex who objected about a chapter about him? Some guy sees one line about him, missing thousands of lines not about him. That's why celebrities are the ones who write memoirs.

And even then, they have ghostwriters and huge teams.

People write memoirs when they’re really old not because they’re really wise, but because they are writing about people who are dead. The living do not like to be written about, especially if you’re writing about really difficult things, like violence, trauma, and abuse. The people involved in that are not the nicest people. And in the way we think about memoir, we see the responsibilities we saddle onto women. We want them to regurgitate the horrible things that happen to them, but then we aren’t there when they do that and they get flack, pushback, criticized, or attacked.

They want women to bleed out and say it was vindicating.

Like, “You were so dumb, why write about something they didn’t have insight on?” Because they wrote one single thing about their personal lives! And then they get asked to write a book! About that one thing! Only about the time they were raped!

And then the fact-checking process after writing trauma or ugliness.

Yes, fact-checking is not neutral. I’ve had people fact check me who have “meant no harm” but were still like, “Yeah, can we call your grandmother about this thing that happened that you mention in one line?” And no! She lives in China, she doesn’t speak English, you don’t have anyone on staff that speaks Chinese, and no, she’s not interested in rehashing or being a source for this line where she mentions something in which she had to go back to horrible things that happen. I wish they would explain that process before asking people to write.

And there are assumptions made on socio-economic backgrounds that play a huge role. It always reveals their blind spots. Like, I get it, you have never been around as many Chinese people that I have. You going to McDonald's to get a breakfast sandwich, I’m never like, does this really happen? But to you, this white editor from this specific class background, you question almost everything that I say because you just think it’s that odd. It really wears me down.

And you’re writing about poor Asian-Americans, poor Chinese immigrants, and in a way that hasn’t really been written about. People who don’t understand often expect us to be embarrassed about things we can’t help.

Totally. It definitely worries me. And you and I have talked about this before—the idea of honor, having honor connected to shame. I try not to create clear conclusions in these stories because it’s complicated. If there is anything that should be shameful, it should be capitalism. Capitalism is shameful. The kind of horrible globalization of capitalism and imperialism is shameful, they create situations where huge masses of people are forced out of their homes and into a place that is not welcoming to them. It is never the individual who has to take the brunt of the responsibility even if it’s often the individual who in that moment causes someone else to feel pain.

One of the things I think is so hard about writing the complexity, is that so little is known about the reality of Asian Americans. There’s so little real discourse, and we kind of pop up in the smallest amount and it’s usually East Asians, usually used to validate some model minority myth and anti-blackness. And so there’s no room in that realm to talk about the reality.

The huge complexity of what it can contain.

Also the stories that maybe even support the bad ideology. I didn’t want to write about immigrants who come to the US and think well of people of color. In fact, they think so poorly about other people of color.

I was going to ask you about that. How did you navigate that while writing it in the work? A lot of the criticisms will probably be about even including it, acknowledging it exists, even though you aren’t condoning it by writing about it. It was realistic.

I wanted there to be space. If you have some kind of terrible anxiety, or terrible darkness in you, the worst thing you can do is pretend it’s not there and try to repress it and ignore it. The performance of: “my life is perfect, I love everything about my life,” or another thing, “my life is terrible, and I am a victim of horrific things and I have never in any way dominated others but I am endlessly dominated.” Whenever you see that, I don’t know. Is there a word for the weird feeling in your soul when you see that performance?

To be either a pure hero or pure victim, purely happy or purely unhappy. It’s never that simple. It never is and everyone in the past, future, present, has loved someone who has hurt someone, was someone that hurt someone. The bonds of power are diffuse. I didn’t want anyone to read these families and feel pure pity. I didn’t want them to look at these stories like it’s a National Geographic anthropological study where you just pity a group of wretched people. I wanted people to feel pity but also show people ways in which they act badly in a lot of ways. I wanted to show that it takes a lot of resources to act well and pure.

It’s so easy to be bad!

Yeah. Survival takes a lot.

I like these stories because you showed everyday acts of cruelty in ways that were unflinching but not unkind. I appreciate the idea that you can find empathy with people who do bad things, because we love people who do bad things, we can’t always remove that love when thinking about the act. But there’s always that space to be reckoned with between what we love about them and what they’ve done, and as long as you witness that space, how dense it is with things you don’t understand or accept fundamentally, it does not make it better but it makes it clearer.

I agree. I think there’s a little of me that’s writing specifically about being the child of people who lived through the Cultural Revolution, and grandparents who were in very high up cadres in the Cultural Revolution. I heard so many stories about it, read so much about it. They lived in a vacuum, which was created just by eliminating all art that didn’t pass an extremely rigid test of purity. It was a time when people could hide behind the righteousness of saying something wasn’t communist, when really they didn’t like a person for a very personal reason.

Being a product of people who lived through that time made me really see all the ways in which I’m a product of a generation who didn’t talk about the really bad things they did. That’s part of the reason why my grandparents and parents are going to die with this pain; they can’t talk about the really bad stuff they saw, did, participated in, condoned, encouraged or ignored. It is a pain that hopefully I won’t have as intensely. I wanted to be, at the very least, a chronicler of those things and not only write about things that would make me sound heroic and ideologically pure.

That intention of discomfort comes across in how you write about bodies, the huge connection between physical and emotional processing. Like the girl who couldn’t stop itching. The way body discomfort and intimacy with parents intertwined as a way to show love, and she felt like she had to be embarrassed by it, but wasn’t actually. It was so sincere.

I read somewhere that when you’re treating Asian Americans for mental health, one of the things that is very common is they won’t say, “I’m sad.” Rather, they’re like, “I have this horrible headache that hasn’t gone away in two months.” A lot of AA immigrants I know find it so hard to emote that I start to literally see it on their skin. I have friends whose skin has literally started degrading and rotting because they’re so unhappy. But they never say. I’ll ask, are they stressed, do they need to talk. And they say, “No, I need a miracle cream.”

“I need to jade roll the pain away.”

Yeah, and I’m like, maybe your pain is not only skin deep. Especially poor immigrants—I don’t think any of the people I grew up with knew what therapy was. I didn’t know what the word for depression was in Chinese until I was twenty-four.

I still don’t! And I didn’t know the word for queer in Chinese until I was, like, twenty-three.

Really?! I love realizing what words we can’t say and realizing the difference between the culture you live in and where you’re from.

There’s never a direct translation.

Yeah, there’s so many blanks in your memories and so many blanks of words. Some of them are the most important words you use, the ones you use all the time with your friends, and it really says something when you can’t articulate the ideas you think about so often. It means something that my family never uses those words, and that I wouldn’t be able to say those words to them. So the body becomes a site of expression.

You had a line that reminds me of this act of expression and failure. “There was no beauty in shaking them off, though they strove for grace, waving their arms like ballerinas.” I wanted to know what you think the difference between beauty and grace is.

That's really interesting! In that line, not what I think, but what the character is positing, is that beauty . . . has some kind of salvation, and grace doesn’t. Grace is that stiff upper lip you want to have because a trembling lip looks so “ugly.” That's what the narrator thinks. But I don’t know what I think. I think grace is something you had to work for, something you had to labor and learn, and practice. And I thought beauty was something inherited. It’s your birthright or it’s not. That’s why I was against beauty for a while—why should something so randomly doled out to some people be of any value? But then, maybe I’m in captivity to a very bland dominant cultural idea of beauty. Why do I think beauty is what people with money and power say are beautiful? I really like your whole thing. I learn so much from you talking about beauty and terror. What do you think the difference between beauty and grace is, by the way?

I don’t think beauty has to have anything to do with grace, it can contain it. Simone Weil wrote so much about both and she thought about grace as this holy thing that you sacrifice to, her idea of beauty had entirely to do with God, sacrificing our bodies to this obliteration upwards. She didn’t value her body, and the more she put herself in horrific situations, the more she felt graceful, and vindicated, closer to what beauty truly was, to what everything humans are not. And that’s all just the exact opposite of what I think. I don’t think suffering helps you transcend. Sometimes pain is just pain. You can learn how to be different people through it, but there’s never one way out. That’s what I like about the characters in your stories—you can see how trauma is inherited in all of these families, and all of the characters work through it differently. They react differently, use it differently.

I don’t really like narratives that justify or look for justification for suffering. I hate when people are like, ‘’well it was all worth it, because. . . ’’ When I was editing these stories I went through this period where I kept looking for stories of people suffering from the minute they were born to the minute they die. These girls I wrote don’t have that life. They don’t live miserable lives without end. They are close to people who either have known or have lived lives of unending misery and they see what that does to a person. And one of the sad things is, it doesn’t make them like that person. When someone has lived with unending misery you want to think they’re worthy of love and forgiveness, but in these stories the girls are saying, “get away from me.”

So as I was writing, I was reading stories of people born into captivity and I asked myself, “What am I doing? Why am I obsessed with this?” I guess I needed to remind myself I don’t need to justify. I don’t ever need to be like, “and so there’s a moment of beauty.” There doesn’t have to be a moment of beauty in every story.

Beauty doesn’t save.

Yeah. Sometimes a life enters and exits this world and it’s hard to say what is it for or how anyone could have intervened and made it better because no individual is responsible for the structural destruction of people. That's what I was trying to show, you feel like you must save yourself and others as individuals, but like, you can’t. That was a hard thing to get across but it was what I was interested in. Jesus christ, we’re really getting into it.

[both drink]