The hours in that bare room in the police station, the exchanges of tension and silence for coffee and reluctant speech, the always hard-to-believe deferral of the request for a lawyer, then the first sentences of the truth or the coerced, mutually-shaped fabrications that will end the interview and begin the trip to a long stay in prison: watching someone confess, if you can find a leak of an unedited video, can’t quite be called thrilling, and only perversely can we acknowledge it as entertaining. But there’s something vital in it, whether the interviewee is guilty-as-hell and ready to talk, like Colonel Russell Williams, or the police are cajoling an unlikely scenario out of a potential innocent who doesn’t know that he should be keeping his mouth shut, like Brendan Dassey of Making a Murderer notoriety.

That confessional impact, the chance to witness the first telling of a story, is something that reporters seek as aggressively as cops. A certain kind of reporter, that is: the type of reporter who turns up on the doorstep of a person connected to a crime, knocks, and talks through the door until she gets the answer she wants: Come in. For cops and for the journalists working a crime story, the interview carries that vitality of the confessional video without the mediation of watching it after the fact: the cop, in that interrogation room and the reporter, once she’s made it past that locked front door into the living room or kitchen, is there with the speaker, listening to the story of a terrible act, being told aloud for the first time.

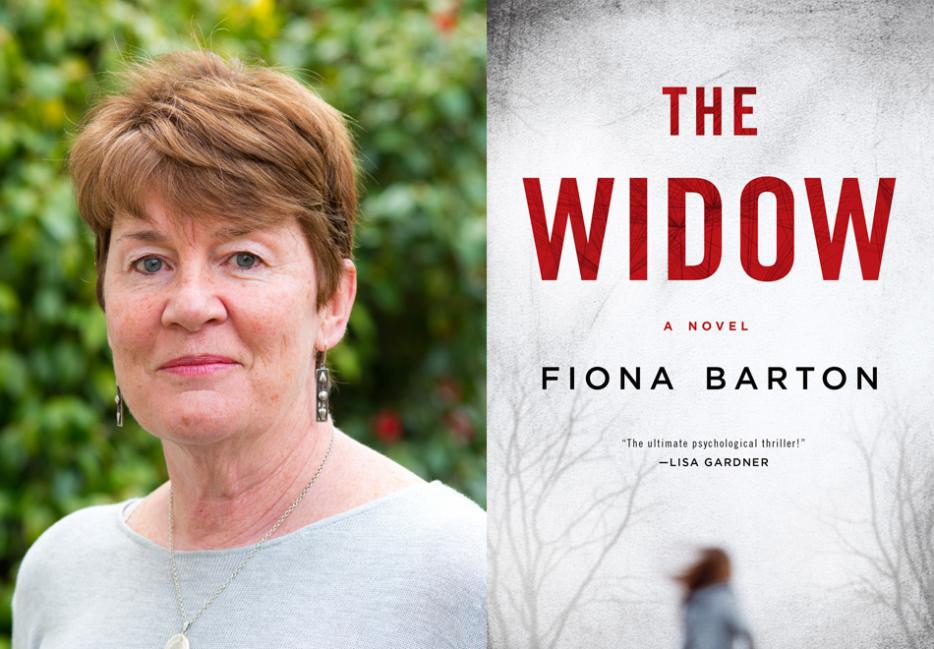

Kate Waters is that reporter, trying to extract the story readers want to know in Fiona Barton’s debut thriller, The Widow. Barton, who was once that reporter herself, (the Reporter of the Year winner has worked as a senior staffer for the Daily Telegraph and the Daily Mail) was initially writing a book focalized around one character, until she realized that there was a sharper way of getting the voice of the title’s widow, Jean Taylor, with her mixture of lies, truths and silence, across. “I quickly realized that other voices would make it more interesting and would unsettle the readers more. I introduced Kate, the reporter, because she was so key to getting Jean to tell her story.” Barton’s book is about the different ways an interview can force a story into the open. The three main characters—a detective, DI Bob Sparkes, Kate Waters, and Jean Taylor, whose husband was accused of kidnapping and likely murdering a little girl—engage in games of talk, with the highest stakes.

*

The last story that Barton worked before leaving The Daily Mail and journalism was the arrest and trial of Levi Bellfield, who murdered four women, including Milly Dowler. Coverage of the Dowler case by a different newspaper, the News of the World, was central to the phone-hacking scandal that led to a long ethical debate in and about the role of media, and led to the closure of that 168-year-old paper. Barton’s work on the case was hack-free and talk-based. “I was investigating the background, interviewing victims that got away, past girlfriends. Trying to understand what made this man kill strangers. And I was seeing a lot of the police.” Her time spent in interviews with the family members of criminals, or watching them in court—these people who spent intimate hours with someone who’d done something horrible—was what led Barton to ask how much each of them may personally have known about the unspeakable crimes committed. The Widow asks what kind of interview might render those crimes speakable.

“I wanted a crime that would be so shocking that you couldn’t forgive someone for it."

An interview about a crime is a game with two players: the interviewer wants as much truth as possible, and the subject wants to control exactly how much truth escapes. Money, notoriety, and promises may frame interviews, but they are all motivated by an intense desire to either obtain or protect the truth: to decide what version of reality makes it into the world. The connection to writing a novel is clear, but when Barton was first turning to fiction from journalism, she found the adjustment difficult. “Right at the beginning, when I was writing, I was finding it so hard. I was trained to write a story in 500 words—crisp, clean, straightforward. Tell the story and move on to the next time. So writing a novel was a bit of a nightmare. And then I realized I didn’t have to stick to what people said. I could imagine—in fiction, I could make it up. Anathema to a reporter. But a wonderfully liberating moment.” Barton’s long career at the papers in Britain is clearly still crucial to how she “makes it up” when it comes to fiction: the interview is her primary narrative tool, the scalpel that gets words, both spoken and thought, emerging from her characters.

Barton’s understanding of the peculiar intimacy and thrill involved in extracting a story for the first time, of witnessing it come into the world, pervades The Widow . “For a reporter, the interview is the best part of the job. Hearing things for the first time, asking questions, being able to ask questions—being paid to ask questions. That moment where you’re discovering something about the person you’re talking to—and you can ask anything you like.” She differentiates between the types of access allowed by varieties of interviewing, and the people at the center of The Widow make it clear which subjects and conversations she finds the most telling. “I’m not talking about celebrity journalism, where there are a lot of rules about what you’re not allowed to ask. I’m talking about the sort of journalism I did, which was about ordinary people who had experienced extraordinary things, who had left the house in the morning expecting to go to work and for it to be a normal day, and then finding themselves caught up in tragedy, or disaster, or incredible good luck. The interview is that moment where people will tell you things, will bare their feelings and what they know.”

*

This thrill is successfully chased throughout the book, whether it’s when DI Sparkes talks a false witness into admitting his lies, or when the widow Taylor begins to realize the extent of the power she has over Kate Waters and the journalistic institution with just a few uttered words—and also how difficult it is to contain a story once you begin to tell it. There’s room for ambiguity here, in how much Kate is morally at fault for what she tells and what she holds back. But there's no ambiguity when it comes to the crime at the centre of the book. “I wanted a crime that would be so shocking that you couldn’t forgive someone for it. Child abduction is the worst thing for anyone who has a child. The very idea that your child is in somebody else’s hands… I felt that it would speak to people, and speak to readers: how do you come to terms with the fact that your partner has been accused of doing that? There is no mitigation for killing a child. It’s just evil.”

An interrogation of the man DI Bob Sparkes believes kidnapped and likely killed the vanished child who is the absent center of The Widow is critical to the novel simply for the lack of satisfaction that it offers. It’s an exchange that only results in doubts and conjectures, with no firm answers. “I’ve not sat in on police interviews, but I’ve seen videos of them, as we all have, on the news. But they’re very heavily edited,” says Barton. In The Widow, she shows us the reactions and motives that lie between the cuts of those edits: the potential satisfaction that a confession, false or real, might lead to, balanced against the unthinkable consequences of acknowledging a terrible act.

In a book that’s almost devoid of non-criminal forms of sexuality, the interview is the close contact that we get. In language, it is true intimacy: finding out what people are willing to say, what they’re willing to tell you, can be as interesting as finding out what really happened.

Barton herself has been on the other end of the microphone or telephone for months now, promoting her novel, answering for the moral precariousness of her journalist, her cop, and her widow. “People have taken such different positions on it. Some interviewers say ‘I loved the reporter, she was a real go-getter.’ The next person I meet says ‘God, that awful reporter, you know, getting in there and making Jean speak.’ But, of course, what unfolds in the book is the question of who is playing who.”