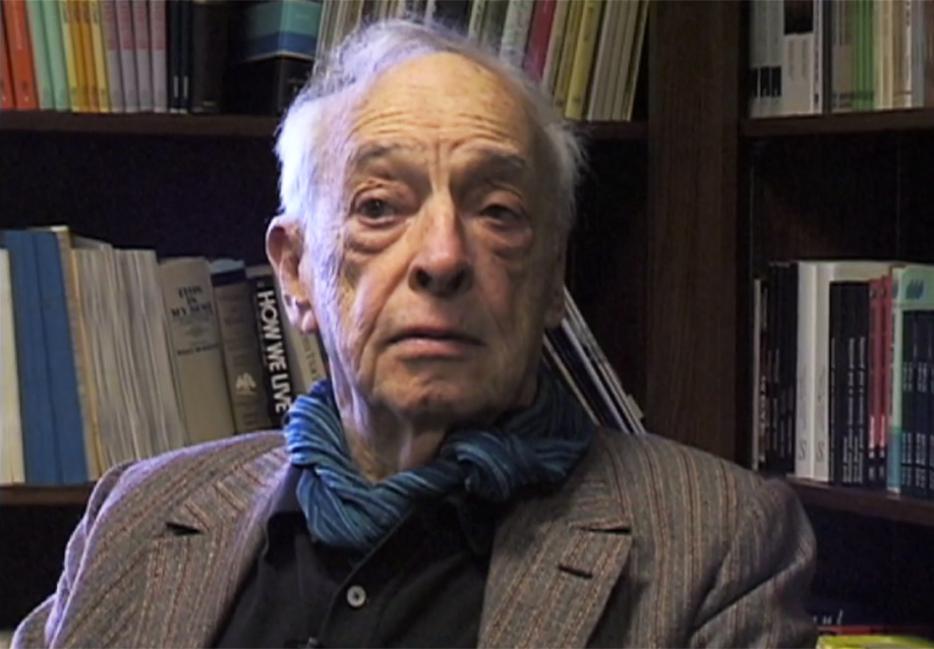

In the very last years of his life, when he was well into his eighties and his memory had more or less gone, Saul Bellow took great delight in uncomplicated pleasures. He liked to feed grapes to his daughter, Naomi Rose, arms draped around her. He’d play Bach on the recorder, the same melody again and again, as the six-year-old girl, whom everyone called Rosie, danced. “She’s so beautiful!” he’d say. “She’s such a little angel!” And night after night, Bellow and Rosie would watch The Lion King.

”Their strange interests matched in those last few years,” Janis Freedman-Bellow, his widow, said recently. “Those were the kinds of things that were eerily perfect, given how difficult the situation on the face of it was.”

***

In 2000, I was one of a dozen students in Bellow’s class at Boston University. We were culled mostly from the arts and sciences college; I was the odd man out, from the film school program. We all understood our weekly meetings of An Idiosyncratic Survey of Modern Literature to be a gift.

Each Wednesday, the students sat around a conference table, while members of the Evergreen program—senior citizens who, for a small fee, could audit university classes; Elie Wiesel’s was a hot ticket—filled out the room’s periphery. They would place a bottle of iced tea at the head of the table, for Bellow. He ambled in, never late.

Bellow chose novels he loved: Denis Johnson’s Resuscitation of a Hanged Man, Joseph Conrad’s Typhoon, Philip Roth’s American Pastoral, Denis Diderot’s Rameau's Nephew, James Joyce’s Ulysses. During the first class, we asked Bellow why, unlike Wiesel, whose class I’d taken the prior semester, he declined to teach his own work. That, he replied, would be needless self-aggrandizement. He was fond of a Yiddish proverb: Why chew your own cabbage twice?

For ninety minutes, Bellow led a loose discussion of the week’s text. He allowed us to unspool theories about the books, and would gently correct us. We were young and often wrong. But that was okay. He didn’t condescend to students or compromise the material. As Freedman-Bellow, who took her husband’s class as a graduate student, told me, “If there was something he felt we didn’t know, he was going to give us the background and have us delight in it. If I know it, you can know it, too.”

Teaching was Bellow’s way of taking a "humanity bath with us. But it wasn’t dirty bath water. When he came to us, everything would pour out in full sentences. It was so richly in him and so fully articulated, that he didn’t need traditional ways of preparing.”

The notes I took are gone, but I remember certain things. The pleasant disorientation of watching Augie March teach Nathan Zuckerman, for example. And the week we discussed Ulysses. That morning, we sat nervously as Bellow took his seat. “Have you finished the book?” he said. Had we read every page of one of literature’s most famously difficult offerings? In a week? Not one of us had gotten to that last Yes. Bellow laughed—not the marvelous, head back, teeth-bared laugh for which he was famous, but a small laugh—and brandished an ancient copy of the book, which, he said, had been smuggled into the country for him in the 1930s. And for the next hour, he read to us from Ulysses and, without notes, annotated it. Bellow’s deep recall, fluency, and confidence seems, now, to be a beautiful, cerebral high-wire act.

Bellow was eighty-five then, and seemed to be in the catbird seat: a marriage to Janis, his brilliant former student; the miracle of an infant daughter, whom we saw in the halls, cradled by her mother; and, of course, Ravelstein, an ode to his late best friend, Allan Bloom, which made the cover of The New York Times Book Review.

Sure, there were instances when Bellow would pause for uncomfortable lengths, or meander a bit before returning to the topic at hand, but at no point during the semester did he visibly, or audibly, lose his way. “He would digress,” said Chris Walsh, Bellow’s longtime secretary and teaching assistant, “but almost always circle back to the point.” To say the least; Bellow could effortlessly speak in paragraphs, structured of exuberantly complex sentences. (This is true, too, of Freedman-Bellow. They were well matched.)

Bellow had taught similar classes for years, going back to his days at the University of Chicago’s Committee on Social Thought, where he’d been on faculty since 1962, and first co-taught with classicist David Grene. The survey course was “his own take on a handful of meaningful books that had formed and shaped him,” said Freedman-Bellow, who took the class in the 1980s, when it was co-taught with Bloom.

Bloom, she recalled, “played a kind of straight man and drew him out in a way that we students couldn’t, because it might have seemed disrespectful or we didn’t want to pit ourselves against him and ask questions that might have seemed overly combative.” Bellow left Chicago for Boston University in 1993, on the heels of Bloom’s death. Classes during the Bay State years were considerably less argumentative; Bellow lacked a counterweight, but we students were neither equipped nor inclined to push him.

The class was not an exercise in vanity. We learned a lot. (It was, I thought, a punishing syllabus.) But as the most famous writer on campus, Bellow was open to the usual criticisms of the “celebrity professor”: infrequent classes, no office hours, and so on. Worse, said Freedman-Bellow, was the belief that he didn’t prepare, that he had no interest in it.“This couldn’t be farther from the truth,” she said, observing that Bellow would talk about riding the L in Chicago because, as he wrote in Ravelstein, he needed a “humanity bath.” Teaching, as she sees it, was Bellow’s way of “taking that humanity bath with us. But it wasn’t dirty bath water. When he came to us, everything would pour out in full sentences. It was so richly in him and so fully articulated, that he didn’t need traditional ways of preparing.”

“There was so much of it,” she said. “You could hold a bucket underneath, you could never have caught it all.”

***

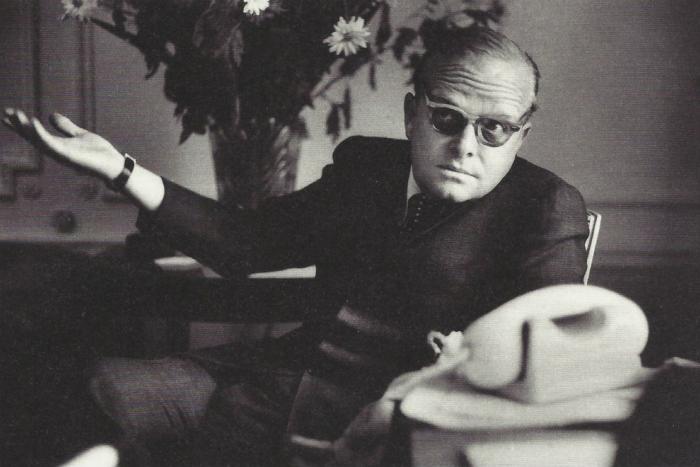

In 2000, while wandering the halls of the university's College of Communication—where I took film classes—I smelled smoke coming out of an office. I looked in and saw a long-haired man puffing a pipe. This was curious, because it was well understood that smoking in classrooms and offices wasn’t allowed. The flaunter of the no-smoking rule was Keith Botsford, a colleague of Bellow’s and, with Bloom dead, his closest friend.

Botsford is one of the brighter people I've ever known. He speaks a dozen languages, including Japanese, and has written in most of them. He worked with John Houseman and spent time with Robert Lowell in Mexico. “Keith is now coming to see me about some prose translations of you,” Lowell wrote to Elizabeth Bishop. “He comes through Rio traffic wobbling on a bicycle—with his large wobbling pipe leading.”11Thomas Travisano with Saskia Hamilton, Words in Air (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2008), 414. (There’s a reported CIA connection to all this. Botsford, wrote Frances Stonor Saunders, was tasked to “keep an eye on the poet.” It didn’t go well; in Buenos Aires, an unmedicated Lowell gave a speech in which he “extolled the Führer,” then “stripped naked and mounted an equestrian in one of the city’s main squares.”) Like many of Bellow's friends and enemies, he was grist for the novels. Here’s Botsford-turned-Humboldt's Gift’s Pierre Thaxter: “Sometimes he was a purple genius of the Baron Corvo type, sordidly broke in Venice, writing something queer and passionate, rare and distinguished.”

I began to visit him each Wednesday. It was sort of like Tuesdays with Morrie, except Botsford would blow smoke into the vents, tell me not to have sex with American girls (advice I studiously ignored), and impart lasting writing advice.

I began to visit him each Wednesday. It was sort of like Tuesdays with Morrie, except Botsford would blow smoke into the vents, tell me not to have sex with American girls (advice I studiously ignored), and impart lasting writing advice (Don’t say “portly” when you can say “fat.” Fewer syllables and everyone knows what you mean). I loved hearing him talk.

Botsford and Bellow, whom he met at Bard, had since 1960 jointly edited journals with such names as ANON, News from the Republic of Letters, and The Noble Savage. The latter publication, their first, had among its contributing editors John Berryman, Harvey Swados (who, in the first issue, wrote about the Floyd Patterson-Ingemar Johansson fight), Arthur Miller, and Ralph Ellison.22Zachary Leader, The Life of Saul Bellow (Alfred A. Knopf, 2015), 549-50. Bellow and Botsford were early champions of Thomas Pynchon and Robert Coover, but managed to reject Elie Wiesel’s Night and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22.

In late 2000, they’d just finished a large anthology of these journals. Botsford proposed, as a means of promotion, an on-camera interview series with a number of the anthologized authors—Bellow, of course, but also Arthur Miller and Edward Hoagland (of whom, he knew, I was fond). He and Bellow would be first. The idea was that, as Bellow rarely did such interviews, the project would quickly find an audience and drum up interest in the book.

On a snowy December 16, 2000, two classmates and I trudged to Bellow’s office with our equipment and, in my pocket, a single page of a dozen questions. For a man of such achievement, his office was conspicuously lacking a vanity wall or—with the exception of the National Book Award for Herzog which hung on the wall—a sense that he was arguably America’s greatest living novelist.

I don’t remember being nervous—just cold. We shucked our jackets and the girls chatted with the men. Having a female crew ended up being good for Bellow and Botsford’s morale; I was happily ignored as the camera was affixed to the tripod and mics were threaded through shirts. The interview went well, with much back-and-forth between Bellow and Botsford. The rest of the project didn’t materialize. Regrettably, I never interviewed Miller or Hoagland.

Several years ago, when Zachary Leader was announced as Bellow’s new biographer (James Atlas had previously published an extensive examination of his life in 2000), I wrote him and asked if he'd found any interviews done after mine. The year before, in December 1999, a “super-lucid” Bellow had been interviewed by Norman Manea. Leader, whose The Life of Saul Bellow was published in May, replied, “Don't know of a subsequent one.”

***

In November 1994, the Bellows visited Saint Martin. He worked on All Marbles Still Accounted For, a novel he never finished. He was in high spirits. “The blue of the Caribbean I see from this open door is my form of El Dopa,” he wrote to his friend, Eugene Kennedy.33Benjamin Taylor, Letters (Viking, 2010), 504. Then, in an incident dramatized in Ravelstein, Bellow nearly died of ciguatera poisoning after eating bad fish. He was in intensive care from Thanksgiving through New Year’s.

The expected route for her husband, Freedman-Bellow said, was long-term rehabilitative care. But that would’ve been fatal. “He had it in mind to do it differently,” she said. Nearing eighty, he demonstrated his vigor by running up and down stairs. A nurse told Freedman-Bellow, “You’d better be careful of that guy. Your husband has no pain threshold.” He wanted out, and went home.

Bellow resumed teaching that winter, not in the classroom, but in his Bay State Road home. Students would remove their snowy boots in the hallway and sit on folding chairs provided by the university. The seminar went on as before.

***

When I took Bellow’s class, six years after the near-death experience, he was strapping and hardy. It wasn’t difficult to see in him the man who, for most of his life, had taken exquisite care of his body. But not long after that semester he began to physically weaken. Freedman-Bellow, Chris Walsh, and university administrators felt it would be healthy for him to continue teaching, albeit with assistance. For a while, in 2002, he co-taught the seminar with James Wood, embracing the model that had served him so well in Chicago.

A year later, a rotating group of writers—including Botsford, Wood, Roger Kaplan, and Martin Amis—was brought in to alleviate the burden of preparation.

***

Bellow was increasingly immobile. “We made a life upstairs,” said Freedman-Bellow. The man who, as well as anyone, could describe the natural world in such detail and vitality—”the riot of life,” as Wood put it—became cloistered to a hospital bed in his bedroom. Upstairs is where the family would have dinners, play music, and receive visitors. “We tried to make it just as much of a party time as we could.”

Old friends stopped by. Philip Roth was “a constant presence” and telephoned often. This was no small thing, Freedman-Bellow told the New Yorker in 2013. “Saul could be repetitive, and a lot of people thought it wasn’t worth it anymore.” (He often didn’t know where he was.) He carried Roth’s The Plot Against America around the house, and took to calling it “the Book.” The world came to Bellow; he even got a house call from his dentist, who performed a tooth extraction.

Wendy Doniger, his colleague at the Committee on Social Thought, visited twice, in March 2005. She had known Bellow since the 1976, when they were introduced at a dinner. Bellow told her he’d just returned from Stockholm. “Saul,” Doniger said, “were you on vacation?” When informed he’d won the Nobel Prize in Literature, “I wanted the earth to open up and swallow me whole,” she said.

Doniger found Bellow’s bedroom to be less the quarters of a dying man than a salon. There were books strewn about (he wrote until the very end) and flowers everywhere. Bellow, who was dressed beautifully and was “as handsome as ever,” had changed. “He was much more relaxed with me than he’d ever been. We’d always had a bit of a sparring relationship in the past,” she said. “In these last visits, there was no edge at all. The edge was gone.”

They talked about the samovar sitting in the middle of the room. Bellow’s grandmother brought it over from Russia, and it had followed him from home to home. They sang together, mostly songs that he and Rosie knew. As the old friends talked, the child went in and out of the bedroom, climbing on and off the bed. “It was like a moment out of time, in a way, as if there were no past and no future,” Doniger said. They told stories about outlandish things Allan Bloom had done. They ate delicious food. “It was the best time I ever had with Saul.”

Some things didn’t change; there are photos, taken at the very end, in which he’s laughing. There’s also a photo, taken the day before he died, in which he’s smiling and holding Rosie’s hand. “It wasn’t all terrible,” said Freedman-Bellow.

Rosie isn’t sure what she remembers of her father, who died at home on April 5, 2005. She doesn’t know if the memories are her own or simply things she’s been told. When she was very young, she remembered a great deal about him. She remembered his laugh.

Fortunately, the work survives. As Freedman-Bellow says, “More than most people, I think, we all of us have him here.” Rosie is a violinist, and recently played a Mozart quartet. Bellow had written an essay about the composer, and Freedman-Bellow read it to her daughter. “I want you to know,” she told her, “what your daddy had to say about Mozart.”

Rosie, who has big, blue eyes and long, straight, golden hair, often asks if she looks like her father. Yes, says her mother, but in truth she doesn’t really see a resemblance. “She looks like Rosie,” she said. “Nobody looks like her.”

For Freedman-Bellow, it is important that people know who her husband really was. Recent years have not always been kind to his legacy. “Yes, of course we know all the mean, terrible things he did as a divorced guy and a terrible father,” she said. “But what about the rest of it? What about the rest?”

***

I’m aware of Saul Bellow’s failings, as a person and as a writer. His famous question—Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus? The Proust of the Papuans?—is grotesque. But that tin-eared line seems, to an extent, to have engulfed his legacy. His widow isn’t the only one worried that he’s been flippantly dismissed as “a dead white man.” At the very least, he’s drifting out of favor. As Sam Tanenhaus wrote, Bellow’s work has “gone out of fashion. The great midcentury emancipator is now in danger of slipping into a forgotten past.”

Nevertheless, Chris Walsh, my old TA—who typed up Ravelstein for Bellow—has undiminished ardor for him. “He was my hero,” Walsh said recently, “and then I got to know him and he was still my hero.”