It’s easy to overlook authors of children’s books. Their work isn’t so much meant to be critiqued by adults: it’s there to fill the spaces in our kids’ brains with words and images and ideas and lessons, then be forgotten for decades until those kids grow up and need stories to tell their own families. It’s a circle filled with dinosaurs and wizards and princesses wearing paper bags in books that have been ripped, drooled on, consumed, and abused.

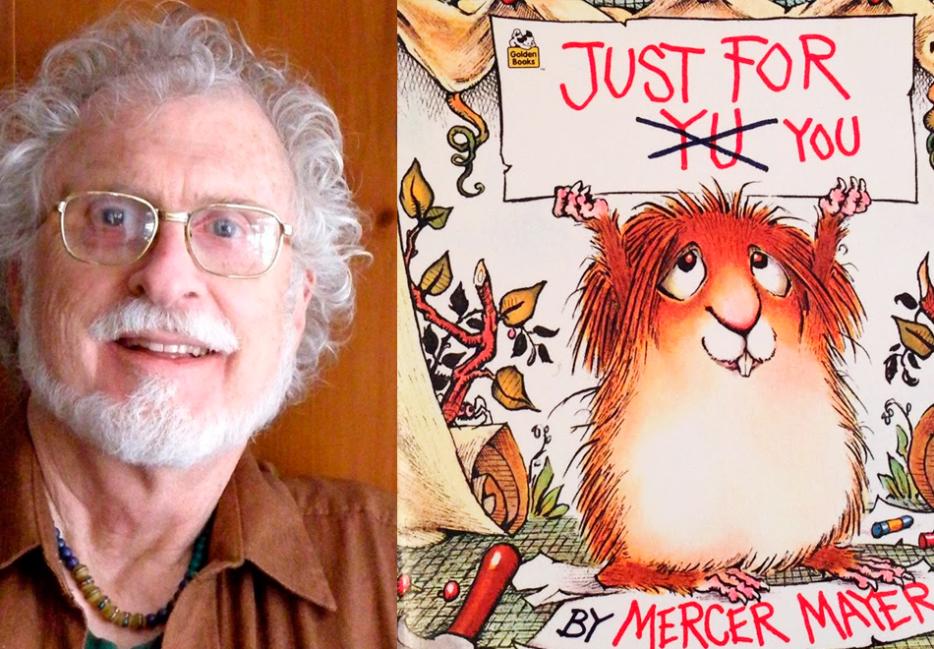

Mercer Mayer has been filling that circle since the publication of his first book, A Boy, A Dog and a Frog in 1967. In 1975 he published a book called Just For You about a hedgehog-looking child who is set on helping his mother with her chores. The book was a surprise hit, and Mayer’s publisher asked for more. Mayer is now 71 and has drawn and written over 300 books during his career, the majority of which feature the same furry kid called Little Critter. His latest book, Just A Special Thanksgiving, was released in September.

I spoke with Mayer over the phone about Little Critter, his career, and mortality. He laughed a lot and seemed to delight in reflecting on a life spent writing for children. I also asked him about the grasshopper and the spider, which will only make sense if you’ve read as many of his books as I have.

*

You’ve worked on this character for forty years. Is that strange to hear somebody else say that?

Mercer Mayer: Well, it just doesn’t make sense because the last forty years seems like about ten. As I’ve gotten older time has gotten extremely faster. So forty years, it’s like, eh, so what? You do change when you age, it’s very funny: your mind changes, your outlook changes, everything changes.

How so?

You come to the realization, hopefully, that this is a terminal situation and you have no idea when, but you have to get behind that in order to go along and see what’s happening in the world. So things you’ve done for many years, it doesn’t seem like many years, at least to me—it just seems like a period of time I’ve done this. This is what I do. I write crazy stories about Little Critter and draw them. But outside of that I don’t get wowed by the thought of forty years gone by.

Is it comforting in a way to have that? So much can happen in forty years—that can be a lifetime. But you’ve also had this strange little character that you’ve been drawing that whole time that’s been a constant in your life.

Well, sure, it’s paid the rent, sent kids to college, all sorts of stuff. Very comforting.

Do you ever get bored by the character?

Yes and no. I have this process I go through all the time, it never stops: When I start a Little Critter book, writing one, I feel like I’ll never write another one again. I can never possibly write another one, there’s just nothing left to write about. And then when I finish drawing and all that, it gets coloured and comes up, it looks very nice. Then, “Oh my god, I have to come up with another, because on my contract it says I agreed to do that.” So I go into a funny state of avoiding all work on Little Critter for a month or so.

What brings you back to it?

I don’t get so far away that I have to come back. But I have to let it go because these stories are very weird. You think about all the things you can write about and think, “Oh, I’ve written about that and I’ve written about that.” And then you think of one subject you haven’t written about—of course, the one subject you haven’t written about doesn’t seem possible to write about. But that’s just your mind going through the typical crap that your mind goes through. You keep messing with the idea and you keep playing with the idea, that’s all you gotta do. You gotta keep messing with it and playing with it. Eventually I start messing with things again and playing with things again, and before you know it out comes a book. Wow! Damn! Look at that. They come very quick. When they come, they come very quick.

Is there anything you haven’t done? I read in an earlier interview that you’ve never figured out how to write about death. I have a four-year-old son who is asking me about death and I honestly don’t have any idea how to have that conversation with him yet, and I was thinking about you and how difficult it must be when you’re thinking about ideas how to translate them for your audience, which is children.

It’s a two-pronged thing here. I think it’s impossible to write a book about death that would be very, very helpful. The problem is this is a marketing issue. Some parents, for example, they don’t believe in anything. Other parents are born-again Christians. Others are Muslims. Others are Jewish. In my house, I am the Buddhist. There are all different takes on this subject of death, [so] how do you approach a Little Critter? It has to be done through his father or mother or the two of them—they’ve got to come to some sort of conclusion about what death is, and you can’t really do that when you have so many views on what death is. It’s not really possible, because you’re going to offend half of them and the other half will probably applaud you.

How much of your experience as a parent weighs into the stories that you pick?

Oh lord, lots. I wrote Little Critter before I had children, the first Little Critter book in [1975], and my first child came in 1981. So there was a lot of time. I was basically writing about my own childhood, or my own fears or my own confusion as a child. Then as time goes by, that childish mindset is something you see in your own children, and it’s interesting to see the logic going behind it because it’s, well, it’s very logical to them all the time. Or it’s very weird and they can’t figure it out, but they just keep going.

You just released a book about Thanksgiving, and I was surprised you’d never done a Thanksgiving book before. Did that idea come from you or did somebody ask you?

Well, actually, we had done a book, Just So Thankful, a generic Thanksgiving book, because they didn’t want to tackle Thanksgiving, which would mean that after Thanksgiving the book would just die. That book did very, very well, [but] for some reason after a couple years the publishers got together and said, “We want a Thanksgiving book.” Why? Thanksgiving has become a big national holiday. So Thanksgiving is almost as big as Christmas.

How much do you work? How much do you have to produce per year?

About three books per year on average.

How long does it take you from concept to finished product on your end?

It takes about four months. Whether it [actually takes that much time] or not, I don’t know. So much of writing and illustrating your own book is a give and take you’re having with the universe: “That doesn’t work, universe, give me something better.” [And the universe will sometimes say:] “Actually, maybe don’t work that day, it’s just not coming.” Then you think, “Oh, I’m going to work this through,” and you work like a devil for two or three days. It’s all about how it’s progressing as an entity—it’s demanding things of you, and you say, “Okay, I’ll do it,” or, “No, I can’t deal with that right now, it’s too confusing.” At least that’s [how it is] for me. But I’ve been very disciplined my whole life working. I have a tendency to work five days a week. Not all day, not during the day necessarily, but four hours, five hours, sometimes six hours.

Okay, so, I don’t want to offend you. I am going to ask this question though. I’m just going to put it out there. You’re 71.

No.

Yeah! No kidding. There’s no reason for you to keep working. Why are you?

Well, it depends on why you’re working in the first place. I mean, technically, I could retire. But then I would get extremely bored and write a book. Put it this way: I am basically retired and I am somehow now writing three books a year.

Do you know how to not work? After all this time are you capable of not drawing or not writing?

I don’t know. I haven’t gone that long without doing it. Am I capable of doing it? I’m a Buddhist and I practice all sorts of meditation, so I’m very much active in learning how to do nothing. So I practice a lot of doing nothing.

Does your Buddhism inform these books at all?

No, not really. Buddhism came out of my reflections on life after a number of years and the books just kind of wandered along by themselves.

What about the character? You do other books and you do other things, but this character, why does it work for you as a storyteller?

It started a long time ago—I drew this funny little dummy of this little hedgehog-type guy, he didn’t have any clothes at the time, and it was called Just For You. [It was] about this little guy who was trying to do all these wonderful things for his mother and making a mess as he goes. The book did phenomenally well for Golden Books and they wanted another one. Then they asked for a couple [more] books—makes sense to do one after the next—and there you have it. It just develops like that.

So you’re actually coming up on 50 years since your first book, A Boy, a Dog, and a Frog was published. Between that book and Little Critter, were you trying to find something that would stick?

No, no, I just did things that came to me. Liza Lou And The Yeller Belly Swamp was one of my first books, like the frog books, and I took it into the publisher when I did my first book—this is back in the days when you could do this kind of stuff—I walked into the publisher of Dial Books and said I’ve done this dummy like you’ve suggested I do, but I can’t think of any words. And she sat down and looked at it and said, “Oh wow, no words. Let’s publish it the way it is.” You always, as a writer or an artist, you always hope your work will sell, because it validates you when you do it.

I never was thinking of a great character, I was just thinking of great books. And when I did this little guy, this dummy called Just For You, the publisher I took it to looked at it and said, “Oh Mercer, you don’t really want to publish another dumb little animal book do you?” I said, “Well, I haven’t published an animal book, first of all. I’d like to publish this damn little animal book.” But then I said, “You don’t need this,” took it out of her hands and went to Golden Books. They thought it was great—they love little dumb animal books.

But more than anything, Little Critter is a reflection of little kids trying to get socialized in the world. That’s what it’s all about when you’re little, and all the things you have to deal with. All of this subject matter is just things that arise in a child’s life, one way or another, and how you resolve them or what you find out about them. But they’re not extremely turgid or in the dramatic sense of losing your pet dog—it’s just an experience, and the way a kid would have that experience.

Before we move on, I want to quick ask you, and I feel like this is a question only someone who has read your books a lot could ask you, but where did the idea come from for you to add the grasshopper and the spider? Finding those little characters hidden away in your images always felt like a treat.

Because I can’t stop. A picture tells a story a little differently from the words. It’s not something I think about—I do it. I don’t literally interpret every word and leave everything blank. It’s a visual experience of the words, and [there can be] many different visual experiences of those words, but mine is whatever goes on with Little Critter. And then these, for some reason, the grasshopper came along first and then the spider, and they just wander in and out of the page and nobody ever refers to them at all. They’re just there. It started off as a funny thing, and then after about ten books people [started saying], “Where’s the spider?” I dropped the grasshopper because he was such a difficult little guy to draw in all these different poses. So I thought, “I want to have a mouse or a frog.” I tried all these things; the spider always stayed. And now I’ve settled on the spider and a mouse because they’re just a funny combination. And they just wander around. That’s all.

Is that something kids notice?

Oh yeah, kids notice that kind of stuff immediately. Kids notice all sorts of strange things. If I forget to have a button coloured on Little Critter’s overalls, I could get mail saying, “Little Critter has no button on.”

Liza Lou is a book I grew up with, but I don’t think I understood that you did it until I became a parent and I went back to it, because it is so completely different from your other works. In the years before Little Critter, how much of that time between A Boy, a Dog and a Frog and Little Critter were you still trying to decide what kind of artist you’d like to be? How much development was happening at that point?

I fell into these books. I came to New York with a bunch of paintings, very Salvador Dali-ish, strange and graphic and gory things that got a lot of attention on Madison Avenue. When I brought my paintings in they saw them, they all, not all but a good number of good galleries, said, “Do you want me to work towards a show?” So I set off to paint for this show, and the sad truth of it is I found out after doing about four or five of these things that the only reason I did them was for shock value, and I had nothing whatsoever to say. It was just shock value and I was tired of doing it, so I just stopped painting. It was stupid. I went to an old friend after a year or so, a friend of my mother’s who had been doing children’s books. She says, “Oh come by, see what I’m doing.” So I went over to her studio and she’d been doing all these paintings of cute little girls in little dresses and little dolls and little animals having tea. Her name was Martha Alexander and she was quite well known at the time. I said, “Oh, I can do that, that’s something I’ve always wanted to do.” When I was in high school in Hawaii I wanted to do children’s books, but the teacher said, “We’re going to spend one week on children’s books because you can’t make any money doing them.” I said, “Oh god, that’s terrible.” So I forgot about it. [But Alexander] gave me the names of editors and publishers she knew and told me a good song and dance to get in there. I said, “Hi, I’m Mercer Mayer, I’m just in from Hawaii, and Martha Alexander says I should give you a quick call.” They all saw me right away.

I wanted to ask you about your writing. You have such a clear voice, and it’s something I discovered in one of your earliest books, which I have as The Bravest Knight but which was first published as Terrible Troll. There’s so much of it that I can see later went into Little Critter, and one of the primary things is you’ve got a clear cadence in your lines, almost to the point where I feel like I can’t read it any other way to my son. It’s always lists of things that the character is doing: “I shined his shoes,” “I cleaned the horse,” “I picked a hat.” Are you conscious of it when you write that way?

I’m conscious of all these ideas in order to get them into a book that used to be 32 pages, now 24, whatever. To get an idea without tons of words, saying practically nothing … a novel, kids aren’t going to respond to that. They want to see something happening and progressing. “I did this and I did this and I did this.” Because that’s what kids do. “I do this and I do this.” So whatever the subject is, you have to get into it and think of all the things you would do if you became the squire to the bravest knight or if you lived a hundred thousand years ago or whatever. You’ve just got to think about all the things you’d have to have—you’d have to have a hat with a big fluffy feather, you work for a knight and travel around making bad guys do good things. It’s not so much cadence as it is listening to things and a way of listing what you would do. And you have to make it exciting because I’m not teaching anybody anything, I’m just trying to get them into reading and enjoying the book.

Do you see an end to this at some point?

Yeah, I’ll be dead. I will be dead. So don’t worry about it, you’ll join me.

Well, I don’t think I’ll join you, but you are right, we are going that way.

Well, you know, you’re going there.

But there’s no reason for you to quit. You’re just going to keep going as long as you can?

I don’t really think about it that much. I really don’t. I never felt like I’m really going to work. Sometimes my goofing off seems like work and it’s like, “Oh crap, I’ve got to finish this in two weeks, because I’m behind so much and behind the ball.” But I don’t envision an end like I don’t envision a beginning. We’re all here now and it’s just what we do. Be here now.