Spoilers within.

An early scene in Bioshock Infinite provides a good litmus test for assholes. You are handed a baseball and told you’ve won a raffle. The prize is the first throw at a public stoning for an Irishman and black woman, and you can choose to throw the ball at the couple, or at the entertainer egging you on. In the end, the choice really shouldn’t be a choice at all, and makes one thing clear: This is a rare video game with a point to make about racism.

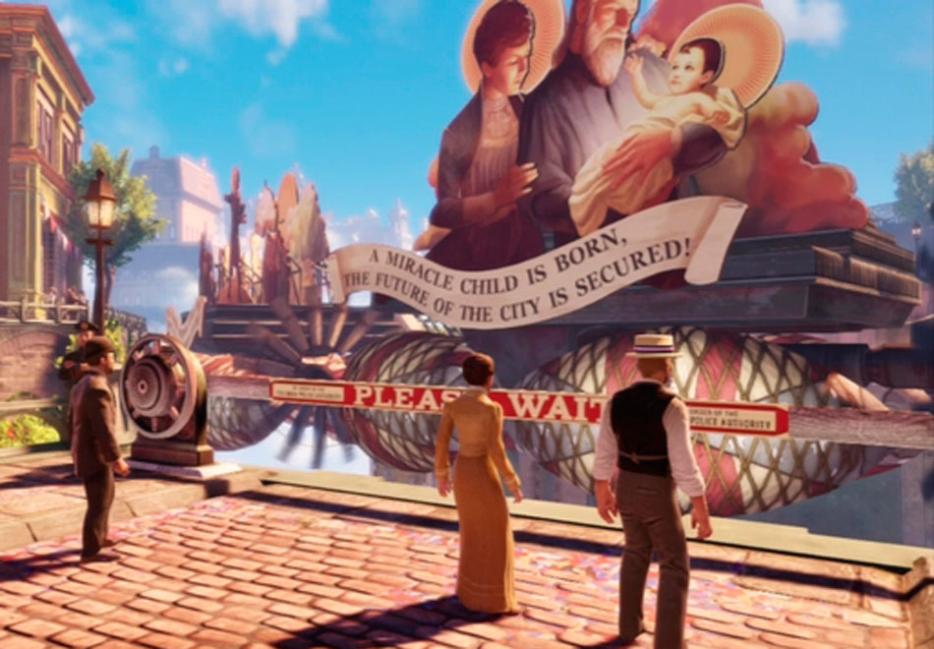

Having just been released at the end of March, the first-person shooter is notable for how it pushes narrative in a relatively young medium not known for being especially deep. You play as Booker DeWitt, who, in 1912 is charged with finding a girl named Elizabeth. She’s being imprisoned in the floating city of Columbia, an Aryan utopia where George Washington is worshipped as a saint and American hegemony is not a political ideal but an airborne reality.

Columbia was built on American imperialism and racial superiority. Founded by the game’s fanatical antagonist Zachary Hale Comstock, Columbia helps end the Boxer Rebellion and is recalled to Washington, D.C. Rather than give up control of the city, though, Comstock and Columbia secede from the U.S. The history of the city—on the surface, eerily clean and peaceful—is told through recordings and kinetoscopes scattered throughout the game, but is also celebrated in one level set in a museum. In the Hall of Heroes, you visit two exhibits: The first recounts Columbia’s role in the Boxer Rebellion, complete with grinning Chinese fighters, while the other is set at the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890, where Comstock and the protagonist took part in the slaughter of an American Indian village. Columbia may be a floating city, but the game boosts its credibility as it bleeds fact into its fictions, establishing its origins in actual historical events.

Bioshock Infinite presents a number of themes worth discussing—fatherhood, fatalism, American exceptionalism, the mix of church and state, and, later, when things get weird, metaphysics—but its approach to racism is necessary to point out in particular, essential as it is to the setting and narrative. In one scene you explore an idyllic beach where white elitists talk with disdain about being approached on the street by “Orientals,” while later, you go in search of a Chinese gun maker who the protagonist points out must have “connections” to own his own store. Playing Bioshock Infinite means confronting a time in American history when racism was not just overt, but also a mundane part of society.

Video games have never been very good with race. The history of gaming contains countless entries that are either blatantly racist (see 1982’s Custer’s Revenge, which features a naked and erect General Custer trying to rape a Native American woman tied to a pole) or classics you probably shouldn’t think too hard about (Punch-Out!! hasn’t aged well). Recently, in 2009, Resident Evil 5 was criticized for featuring Africans infected by a disease that essentially made them zombies who chased the game’s white protagonist. Capcom, the game’s developer, denied the allegations.

Racism is often treated by video games with the complexity of a Saturday morning cartoon. Take the Mass Effect trilogy, arguably another high point in the current generation of console gaming. In the third entry, your goal as Commander John Shepard (who is by default, surprise surprise, a white guy) is to defeat the god-like Reapers by uniting the most powerful alien civilizations. There is a millennium of hate and prejudice between the different races, all of which is overcome by shooting your way through 30 hours of gameplay. Besides the tidy conclusion, the problem is the aliens aren’t real. No one is muttering on your morning commute about the influx of Krogan immigrants taking our jobs. Whatever statement the game might have been trying to make about racism is somewhat diluted by the fact that the persecuted look like lizards on steroids and happen to be handy with shotguns.

That Bioshock Infinite doesn’t conclude racism can be solved with a boss fight—spoiler alert: it isn’t solved at all—is what makes the game so refreshing and others embarrassing by comparison. In the second act you meet the Vox Populi, a resistance/communist group determined to take over capitalist Columbia. Daisy Fitzroy, a former black servant who may have been framed for murder by Comstock, leads the Vox and later co-opts you into helping them. It would be predictable if the game simply led to you fighting on the side of the oppressed minorities, but your eventual decisions, as Fitzroy puts it, “don’t fit the narrative,” and—okay, real spoiler alert here—she turns on you.

Fitzroy, of course, doesn’t have to help you, and it’s presumptuous to think that she will at the expense of her political motives, just because you happen to not be a total racist. Bioshock Infinite’s racial complexities evolve further when the Vox begin executing Columbians and Fitzroy holds a gun to a small white boy’s head, but the point is proven: character isn’t defined by skin colour.

Let’s acknowledge a couple of problems with the game right now. Yes, you are playing as a white guy. He’s a complicated white guy with a troubled past! But he’s a white guy. The ubiquity of this class of characters is made all the more clear when a game actually does feature a female hero or someone who happens not to be a Caucasian guy with a buzz cut and a gun, although recent releases do suggest storylines may be trending in that direction. The Walking Dead starred a black professor (who, uh, is also technically an escaped convict); the last two games in the Assassin’s Creed franchise featured a Native American man and a woman of French and African heritage. (That being said, the upcoming entry in the series stars a white pirate. Anyway.)

It’s also easy to say highlighting the racism in Bioshock Infinite is to skim the surface of what the game is about. This is true. The original Bioshock was basically Coles Notes for gamers who had no idea what objectivism was and didn’t want to slog through Atlas Shrugged. This sequel, however, makes bigger statements than ham-fisted indictments of a philosophy, and by the time you reach the fantastic third act, the racism you encountered in Columbia may well be a distant memory.

That’s fine. What’s special about Bioshock Infinite is that it can intelligently approach issues of race and still have more to say, at a time when video games are still in their adolescence as an artistic medium. Bioshock Infinite won’t go down as gaming’s Roots, but it’s at least a step away from lizards on steroids. That alone makes it worth playing, talking about and, hopefully, learning from.