Several years ago, when it seemed that he might be dying from cancer, one of Derek McCormack’s friends bought him some clothes—beautiful clothes, like the carnivalesque suits and painted dresses that bewitch the characters in his stories. Survival turned out to be a problem, because none of them fit anymore. The other day, McCormack told me: “Part of me now is like, Oh my God, if only I had a little more cancer, just for a couple of weeks. I could lose, like, 30 pounds.”

McCormack has a devious sense of humour: “What’s it called when clothes commit suicide? Deconstruction.” In his books, dutiful straight men get unstitched by the stylish and the freakish. “All monsters are queers,” Elsa Schiaparelli declares in 2009’s The Show That Smells, which imagines the fashion designer as a vampiric parfumier, casting no reflection through the halls of her mirror maze. She vows to wed a married woman before snacking on her baby. McCormack delights in anachronism, carnies and old couture and dead country singers. His sequined prose is concise yet gaudy: “Spirits step from the spirit cabinet. They’re models. They walk like models. They walk like they can’t walk.” Many words appear over and over again, a series of sinister poses. Reading these sentences, each “atelier” or “organza,” I think of a mouth sharp with jewels.

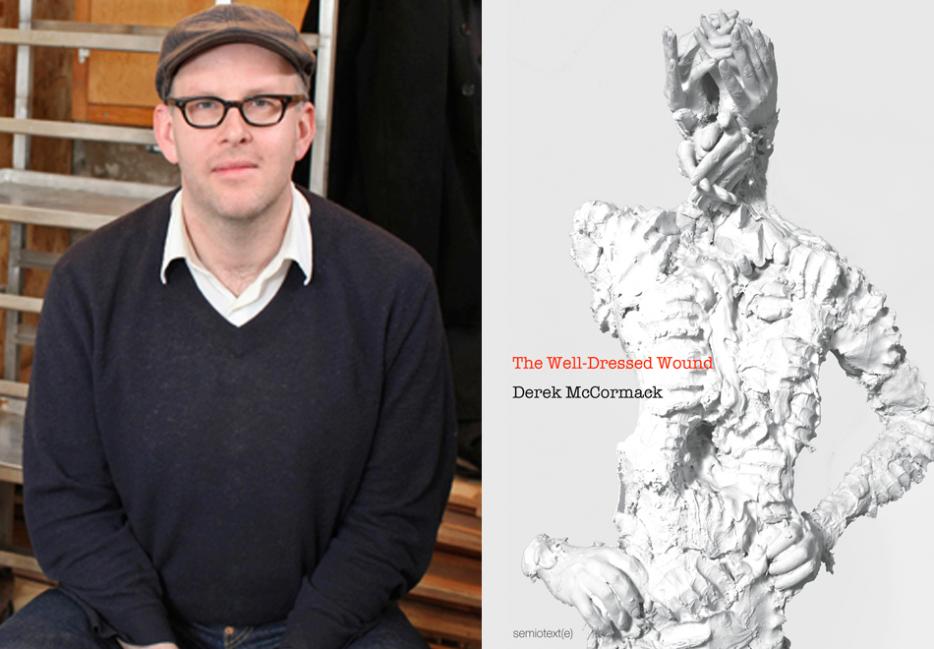

Despite some notable fans, Dennis Cooper among them, McCormack has long made a living working at Toronto’s Type Books, and calls his own novels “unread.” The new one, begun as he got sick, was written in a terrified fury. The Well-Dressed Wound opens with Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln holding a séance for their dead gay son Willie, a ritual that also summons designer Martin Margiela, a.k.a. the Devil, a.k.a. “King Faggot.” Ghosts stalk the catwalk wearing chic shrouds. Gettysburg is their lookbook. Most of the Civil War dead were killed by disease rather than combat, and in that dysentery, measles, typhoid fever, diarrhea, and tuberculosis, McCormack finds a symbolic virology akin to AIDS. On his stage, the minimalist whiteness of Margiela’s headquarters might equally be pus, cum, bandages, a label, a flag, or the runway that leads into the beyond.

*

I had this perverse fantasy of a genteel Spielbergish [Abraham] Lincoln movie with your dialogue, like when Stephen Foster says: "What do I care about the country? What do I care about the war? I care only for clothes and cum and seroconversion."

I'd love Spielberg to do that. He really missed out. I don't think Stephen Foster was very genteel by that point in his life, when he was living on the Bowery. From what I understand he was sleeping in a basement with 80 other people and drinking turpentine. And then, I was curious after I wrote it—everyone thinks Stephen Foster was gay, which didn't even occur to me, but I guess his diaries were expurgated or bowdlerized by his sister. And then I read a novel where he was gay, but I don't know. I always think everyone's gay, so...

It's funny that this book comes out not long after that Larry Kramer one.

Yeah!

I haven't read it, but it's 700 pages long or something like that, and he basically argues that almost every notable person in American history was gay.

I love that. I haven't read it either, but I did feel a little kinship because I often feel like that. I mean, as soon as I am interested in someone I think they must be gay, but I also think that gay people are obsessed with thinking other people are gay. And obviously it's because these things are legitimately lost or blanked out or suppressed, but on the other hand, with me ... it's like with actors—I can't think an actor is attractive without thinking they must also be gay. Which is not to say they're going to have sex with me. If they're gay there's less chance they'll have sex with me. But it's a weird mania. I should ask you, do you think it's an older-generation thing? I spent so much time looking for signs as a kid, because there was so little out there, and then even the people who were out there when I was growing up—oh, David Bowie is. He wasn't! I wonder if it's an older generation who's just trained to care about signs and signals and references and secret things.

Well, there was Kristen Stewart a month or two ago, saying things like, "I date men and women, but I don't want to call it a specific thing." And that feels very ... I don't know, of the moment?

Yeah, I agree. I think that people younger than me don't care about those labels, but I'm from a time when those things really seemed to matter, even though in the long term they don't matter at all. And I see that when I read—what was that book by that hustler?

Oh, the Hollywood one? [Full Service, by Scotty Bowers.] And he names all these different people, like Edward VIII.

Or even Kenneth Anger, right? That stuff really matters to a certain person, and now it's not a surprise to anyone. When you think about it, if I were Gary Cooper in the Thirties, I would've slept with everything too. I don't think those labels apply to anyone anymore ... but that did interest me about Stephen Foster. Although Abraham Lincoln is the one who gets that all the time, that Abraham Lincoln was gay.

I was thinking, it's weird and kind of interesting that the two presidents most often rumoured to be gay are the ones on either side of the Civil War. Everybody knows about Lincoln, he slept in the same bed as another man when he was younger, which could mean a bunch of things, including that it was cold in the middle of nowhere [laughs].

Yeah, exactly.

But there was also James Buchanan, the only president never to marry. And one of them is this beloved martyr, while the other is very often believed to be the worst president ever.

He seems to have been. I remember reading Margaret Leech's Reveille in Washington, which won the Pulitzer in the 1940s, and I think even in that book there are glancing references to his queerness. There's one line about how he wore a big cravat like a goiter around his neck, just pointing out the peculiarity of his dress, and of course the way he lived. And then his retirement with that other guy. I guess that also fits in with some … I was going to say old sense of gays being sick and weak, but that's also my sentiment too [laughs], so. I guess I have an attachment to that 19th-Century idea too. But he was a terrible president. Lincoln, I've read books on how he was gay, and I'm never ever persuaded—not in the way like if someone says Walt Whitman wasn't gay, I think that's ridiculous, but the sleeping in bed together and stuff, I don't know. That sounds more like life on the range or in any tenement or in any frontier situation.

I think also in your book, when you say that all the dead soldiers in the Civil War were gay, it's obviously more metaphorical than Larry Kramer's intent.

Yeah. I haven't read the Kramer, so I don't know—I love the thought that he's seriously arguing that they are. Although the Civil War is interesting because there are very few records of men being charged with sodomy. There are some, but God knows there must have been a lot of fucking in the Civil War.

I was thinking, not a lot of writers we still remember now were actually combat soldiers in the war—there's Ambrose Bierce, who tended to write about it in this horrific sense, like in "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge," that reminded me of your book.

Oh, that's nice!

But I can't actually think of many novels about the Civil War. And the best-remembered writing from it is Walt Whitman's (often homoerotic) poetry. "O Captain! My Captain!"

He also has that poem "The Wound-Dresser," which I glancingly reference. That was sort of a mistake, because I read "the well-dressed wound" as a phrase in a medical book about ulcerations or foot surgery or something and thought it was nice. I've read lots of Civil War stuff, but you're right, the Whitman—there's a great argument to be made, and that woman from Harvard made it in her really nice book about the Civil War, which I can't remember—that Emily Dickinson's a Civil War writer, because everything she wrote was basically from that period. There's a little bit of Melville. Bierce, I don't love his writing so much, but I love the tone, that cynicism. It's a nice contrast to Whitman. Although I find all of Whitman's Civil War stuff really affecting, in part because I guess, with the battlefield stuff, I can't imagine the battlefields, but I can't imagine the hospitals either. I have a terror of hospitals, and I always end up being in hospitals, and I find it sort of traumatic, so thinking about those Civil War hospitals, I [pantomimes nervous breakdown].

The corollary of not being able to recall much Civil War fiction is that there's vast, vast amounts of material on every conceivable historical or social angle. A lot of surviving letters or diaries, too. And there are multiple books that are just about disease during the Civil War. Some of the common images from those hospitals are myths, like the idea that there all these amputations being done without anesthetic. The patients were almost always sedated with chloroform, but—there's this memorable phrase in one book I read—they only used enough to make them "insensible to pain." So you had all these half-conscious soldiers moaning as if sleepwalking. It sounds like the doctors were not sadistic so much as incompetent.

The Union's surgeon general at the start of the war was 80 years old, and he had been in that position since the John Quincy Adams presidency, and he thought it was an extravagance to buy medical textbooks. He died of "apoplexy" a few months into the war, and his successor waited for battles to happen before buying vital dressings and supplies. In a lot of army memoirs you read about medicinal alcohol that mysteriously went missing, and they would use mercurial compounds to treat, like, dysentery, even though it was already controversial. There are many differences, but that disastrous non-response seems to parallel or anticipate the AIDS crisis.

Oh, I think you've spoken that better than I could. It surprised me, really basic facts—like, there was no system to get the wounded off of battlefields, because there were no hospitals. I think the South responded better, but it's shocking there was no stockpile even of things like dressings, you know? It was a struggle the whole Civil War to get lint to stuff wounds. I think there are comparisons there to AIDS for sure, and you're right, it's the non-readiness, it's the fumbling around, it's being this far away from finding out that you have to sterilize your saw between patients. They were so close in time, they just missed it. And then you have weird little miracles—it's my understanding that the Union had more cotton, so they sewed stitches with it, which caused fatal infections. And in the South they ran out, so they used cornsilk, which was boiled first, so you actually had fewer infections ... The other aspect in the book is fashion, and how the South was transformed by clothes being made into bandages, clothes worn as bandages, and the sense of what was proper for a person to wear being reduced to [outfits] of corn-husk dresses and underwear as an elegant thing to wear.

You're right about the Civil War literature: there's a lot of stuff about hospitals and doctors. There are so many stories about amputations, but there aren't so many stories about how—and I didn't realize this reading so many of the books until I got the right book—the situation was worse for black people. Like, there were no hospitals even in the North for black people, or very few, charitable ones. And then in the South there was nothing. They could not get doctors and nurses to serve black battalions and the black populace. So, yeah, you have the horror of the army hospital, and then you have the horror that there are no hospitals for millions of people. And then you just have the general horror I have of hospitals … I can feel my stomach turning.

Did the idea for the book predate you getting sick?

It did, but it was very different. I love reading books about war, and I had gone through the Second World War, and I read that book Washington at Reveille and I thought it was a beautiful book, and it got me thinking about the Civil War—I guess my first thing was thinking, Oh, if there was a Margiela store in Washington during the Civil War, boy would I have liked to have gone there. I wonder what the prices were. Would they have my size? And I think that was a reaction to the sense that Margiela at his peak was a wartime designer, in my mind reminiscent of the Civil War with cotton shifts, everything makeshift, actually, and the blood on things. Using a powder puff with a safety pin to make a brooch. But with Margiela I think it also hearkens back to World War II, which is the most famous time of designers making do, with fake nylons and reusing drapes.

I had been reading about it, and then I got sick, and it turned into a different book. As you said, it started as quite a genteel thing with lots of people talking, and it was going to move all over the place, and then it turned into a scream. For a long time I didn't know if I was going to live, and everyone said, "Oh, what do you want to do, what's your biggest wish?" And I always said that I wanted to finish a book, because in my mind it's part of a trilogy, with The Haunted Hillbilly and The Show That Smells. So I found myself racing with what energy I had to write a book to end a trilogy that I'm not sure anyone cared about, and in the end I don't know why anyone needs this book, anyway. I mean, it's a nasty little thing. Kind of one long pus-y scream.

When I was in the hospital and I came out of surgery, I had been given a spinal catheter for painkillers, and they discovered a day after my surgery that it had not been pumping any painkillers into me. And by that point I was hallucinating there were bugs, and someone had stolen my teeth, and there was a castle outside my window—I saw a slideshow in my room of chopped-up bodies fucking each other, like, legs fucking legs. I realized afterwards that was my Civil War readings coming back. Also, I think it was a way for my mind to permanently kill my libido, because I thought, I'm never going to think about sex again. I'm never going to have—not that I had that much sex before. But I'm lying here with four new holes, and something happened in my brain to make sex so disgusting and so tied to horrible surgery and infection. So when I wrote [The Well-Dressed Wound], I was writing it like I was in a rush, even though after it was clear I was going to live I could've finished it, but the impetus was to write something fast before I died—I felt like it was a bit of a pained scream, as I said before, and that I was losing that as I got better. The early drafts bear no resemblance to what happened after.

I'm glad that you said "nastiness," because there are definitely these theatrical sex scenes as in The Haunted Hillbilly or The Show That Smells, but they seem much harsher here. I wasn't even sure if you had been able to write in that condition. What was it like to write while you thought you might be dying and then go back—like, "Well, I'm alive, so I guess I have to revise this"?

Well, first of all, I was barely awake most of the day. I would lie on my couch with my computer on my lap—to be totally graphic, I had holes in me that kept leaking pus and bleeding, and they would get on my computer. So I was constantly wiping it down. And a small part of my mind was rational enough to aestheticize that and think, Wow, that's fantastic. This is, like, beyond Genet. But mostly it was exhausting, and without sounding too therapy-session, at some point I thought, I'm really angry, and nothing interests me that doesn't sound offensive to me, that isn't screaming at myself or screaming at someone else. So that's why you get the exclamation marks. And then all the blank passages without exclamation marks—I wrote those passages, but everything needed a real sharpness and testiness.

I've been sort of sick my whole life, and I feel like in my other books, there was always a little glamorization of sickness. I remember being very ill in my twenties, and I spent a long time in the hospital, and I made a point of thinking that I was going to sexualize that experience. Like, the only way to endure this is to make that catheter and the sick smell of hospitals hot ... I feel like The Well-Dressed Wound, I did take it another step there. I had always used it as a kind of camp thing, but I guess I was just trying to enact that little hallucination I had in my room, which was ... disturbing, but also serving a purpose of, I have to kill sex in my mind. I have to kill pleasure. I've always glamorized hospital rooms, but I'm going to have to glamorize this, and it's impossible because it's so grotesque and I'm in so much pain and it's the limit of what I can do.

That's also a standard line in literary biographies, right? "He was a sickly child." There's that incredibly blasphemous passage [in The Well-Dressed Wound] where the narrator is basically jerking off to elegiac Civil War photography [both laugh].

Yeah, the sickly child, that was me. And yet I had always tried to make it work for me. Even when I was diagnosed the first time with cancer, I thought, God, my whole life I've spent wanting to be evil, or powerful, or villainous, and now I have the worst, most villainous shit inside me. Now I'm the most powerful I've ever been, because I have this deadly crap growing inside me. And it was not a huge comfort, I was hoping at some point it would be a huge comfort [laughs], but it did seem like the next step in a very long series of steps for me towards doing more than being okay with being sick, actually making it something enviable and beautiful.

I was looking at your ... interview? conversation? with Joey Comeau from a few years back, and there's a part where you said, "I dream of being evil." The Eartha Kitt thing. "I want to be wicked / I want to tell lies." Often the good guys in your books are these bumbling saps, and all of the most glamorous and charismatic characters are, you know, vampires or monsters. What is the appeal of evil to you?

The appeal is ... I hate talking about childhood, because I can't separate my childhood from my current psyche. I was more grown-up when I was a child than I am now. That's a complicated question. The easy answer is, "Oh, I got beaten up a lot." And by "a lot" I mean a lot. Like, I could not go to school sometimes. I was harassed to such a point in junior high that teachers and the principal, their only plan was, they let me out of school 15 minutes early so I could get a running start. So certainly that was part of it, to be able to have revenge. That said, I think that's too easy, because I never really had those simple revenge fantasies. In fact, my revenge fantasy in high school was always that I would get beaten to a point where I was almost dead, and get carried through the halls, and that the cute boys I loved would feel bad for me. It was like a martyrdom that turned me on.

And going back even further, even before I was bullied I knew that I was a little faggot, and there was something wrong and to keep it secret. I guess I was bullied when I was younger, because I would get called a faggot at a very young age, or get shouted at, or get called that by a teacher. And my answer was always: "Yes." So we were at an impasse. I was never one to say, "Yes, so what, it's normal." I was always one to say, "Yeah, it's the most abnormal thing in the world. And that makes me better than you." I guess it was a little revenge thing. I never stood for my rights and said, “No, I should be treated like this,” which I think would've been healthy. Instead I was like, "You're right, I'm sick and I'm wrong and I'm going to be the wrongest thing that there can be." My impulse was always to push that, so that involved writing, it involved finding the evillest things I could find. The Marquis de Sade, Baudelaire. Fashion for sure was part of it. Music.

It also turned into being very wary of the gay world, because it never occurred to me as a young person to be part of a community where everyone felt like freaks, because if you're in a community then you can't be a freak. There has to be one freak, or maybe two freaks. Otherwise you're not a freak. And it felt necessary to preserve that freakishness. It's also physical—I remember the first few times I jerked off, I thought, This is too ... nothing. So I would try it with cutting myself or stabbing myself or something, which might've come from the Marquis de Sade. That was before I was really sick. But when I got cancer everyone was like, "Oh my God, I can't believe it, this is the best moment of your life." And in a way they were right, because I'd been waiting for it my whole life, something that big and awful, if not trying to induce it in myself.

John Waters tells this story about the formative influence of the Wicked Witch of the West screaming: "Who would've thought a good little girl like you could destroy my beautiful wickedness!"

I understand that, because I was the Wicked Witch of the West for four Halloweens in a row as a kid.

I demanded to be a witch one year.

I'm with you. I wanted the green ... I loved everything about her. I hated everything about the Scarecrow, the Lion and the Tin Man. And Maleficent's another one.

A friend of mine did this zine about their identification with all the queer-coded villains in old Disney or Don Bluth cartoons, who are so often effeminate men or butch women. Ursula, Jafar, Kaa the python.

It's the same with Batman villains for me. Even now, I just watched North by Northwest, and I forgot that Martin Landau's character was clearly gay.

I loved the Joker.

Oh, yeah, the Joker was it for me. Although now I can't believe when I see pictures of Cesar Romero, that mustache with the makeup over it ...

It's not a good look.

I feel bad, because I feel that it's an identification that a lot of screwed-up kids make. I just can't believe I never outgrew it. And I feel like it might be stronger now than when I was a kid. That's why I think I liked fashion so much as a kid, because designers are all supervillains. They're just the most horrific people, and radiate it. Karl Lagerfeld's the easy one, but even to the low-level worst designer, it's a combination of dumbness and aesthetic sophistication. You sense the using people, the selling of people, it's all ghastly.

I've gotten so into fashion and beauty recently—I kind of did when I was a teenager, and then I distanced myself from it, and now I'm completely obsessed with it again. The transformational qualities of it. A little while ago I was invited to read at the [Art Gallery of Ontario], and they were like, "We want you to do something about Canada and place." So I decided to talk about my childhood fixation on Grenadier Pond, and the legend that there's a company of Grenadiers who fell through the ice, and their frozen bodies are—well, I guess they're only frozen part of the year. And I put on this sailor uniform, and I tried to make myself look like a prettified Victorian corpse. Like the engraving in an old temperance pamphlet or something.

The writer Arabelle Sicardi likes to say "beauty is terror." That whole idea—in your first book [Dark Rides] there's a story where "Derek McCormack" sees his dead grandfather at the funeral home, "the powdered face and the rouged lips." I'm also thinking of another line from that Joey Comeau interview, where you described "an evil glamour that doesn't make us beautiful, but that changes what beauty is." Because so often, more with beauty than fashion, a good look is not too far from monstrousness. Which I'm into.

Yes. Yeah. Which is why Leigh Bowery is such a legend, because it's Martian, what he managed to do. Part of what I love about fashion is the insane cruelty of it. In a way I feel like fashion owns me like cancer does. It doesn't matter what I do to make peace with it or follow it or live with it, it's always got me bested. It's always in charge. I tried to do that in The Well-Dressed Wound—I think the most important part of the book for me is when Margiela says that fashion made death, and death made AIDS. I've always loved fashion—I've always found there's an enormous thrill in buying designer things that are overpriced. It's an incredible feeling owning it, and the remorse is incredible, and the stupidity of it is incredible.

For me, fashion is so important, and for me it has nothing to do with self-expression or style. I've always tried to subsume myself in a fashion designer's vision, which I think is the most callous thing in the world, and the most unforgivable. That's what I want, I want to be a sacrifice to that designer's whims. God knows over my life I've spent way too much money on clothes, and no one ever knows, because as soon as I put them on they look like crap.

Like, the social—

Yeah, it's a social thing or an anthropological thing. I know for a lot of people clothes are a way to get laid or express sexuality, whereas I feel, like with medicine, clothes are a way for me to maybe neuter me or kill my sexuality, which is the appeal. I want to be desirable only because I'm fashion. I don't want you to think about what's underneath the clothes, I just want you to think, Oh, he's desirable because there's that Margiela tag on it.

It's like you want to be a mannequin, almost.

I do want to be a mannequin, yeah. I want to be a mannequin. But a wax mannequin from the 19th century, one that melts in the heat and flies stick onto and decomposes. I don't want to live forever.

Do you read a lot of current fashion writing? In your previous books, many of the references are historic ones—Nudie Cohn or Coco Chanel or Elsa Schiaparelli. But then in The Well-Dressed Wound you mention Rick Owens, J.W. Anderson ... and a lot of the clothes you describe are these, like, genderless deconstructed rags, on anonymous models, which made me think of Eckhaus Latta.

Yeah, I love them. I don't think I've ever seen it in real life, which is the story of my life in fashion. I don't live in New York or London, so it's always a length of time for me to find out about something, and then when I'm in New York I get to find out what it's like in real life. But no, I do follow it, and before I got sick I had a fashion column for the National Post every two weeks—no one read it, why would they—so I got to interview, like, Viktor & Rolf and Nicolas Ghesquiere. [But] my Margiela obsession lasted a long time. I was wearing him before I thought about writing about him, and then I feel like in his prime he was such a great artist that I was happy to—a lot of the outfits in [The Well-Dressed Wound] are just copied verbatim from a Margiela catalogue, with some changes.

But I'm really unexcited at the moment about fashion, which I find frustrating. I guess I love to have my fashion genius that I adore, which is reflected in the books. In this one it's Margiela, clearly. I don't have that big hero right now. I loveAndre Walker, he's been around since the '90s, he shows small collections—he's like my fashion hero. I guess I could say Rei Kawakubo, who I've worn since high school, but that's been so long it doesn't have any shock of discovery. She's like Picasso or something at this point, you know?

I think J.W. Anderson has made the most clothes that I'm coveting right now. I'm so sad, because—I think it was a year or two ago—he designed these "men's shoes" that had giant platform heels, and they were really feminine. But they pop up on eBay occasionally, that's your only hope of buying a pair now.

He's great. In fact, I was in New York with two friends, we went to Creatures of Comfort—they tried on a lot of J.W. Anderson, which I kept handing them in the dressing room, and it was not as expensive as I thought it would be. And it fit like a dream. Despite growing up in Peterborough, I was very lucky to have parents who took me to Toronto every week, so I got a subscription to The Face when I was, like, 11. I coveted clothes for a long time. I remember going to London with my parents—they said we were going to go to the National Gallery, and I said, "No no no, we're going to go to Vivienne Westwood, and we're going to go to Kenzo." And we did. I had parents who indulged me. I remember going to the first Commes des Garcons store in Soho when I was very young—not that that in itself is so magical, but it does make my heart pang for my parents, who put up with that, you know? Who thought that was a legitimate thing for a 12-year-old to do. And even then the prices just astonished me and impressed me.

I think in terms of the book—in my mind I call it the country-music trilogy, but it's just as equally a fashion trilogy. I've always liked to buy Margiela when I can, which is usually second-hand, but I did go a little nuts on buying vintage stuff, like a vintage ponytail bracelet and vintage repurposed-chandelier stuff. Stuff that was totemic to me in writing [The Well-Dressed Wound]. But I do that with every book. Whatever I'm writing about, I have to own part of it. When I was writing The Haunted Hillbilly, I bought this person's photo album because their parents had visited [Nudie Cohn's] store in Nashville and had little pictures that were never published. Schiaparelli, with The Show That Smells, I have a Schiaparelli wig and I bought a hat. It's a stupid, stupid waste of money for someone who lives so far beneath the poverty line that I can't see it from where I am. I had finished a novel before I got sick, about Count Chocula, and that was much better, because you can find that shit at yard sales.

I was curious about what you wore as a kid in Peterborough.

Before I discovered The Face and new wave music, I wanted to wear what all the kids were wearing, so I remember an urban-cowboy phase, where I had cowboy boots and a plaid shirt. But then, when it got serious with me and music and fashion … when I was 14 or 15 I bought a Jean-Paul Gaultier, and for my high school graduation I wore Gaultier and [Yohji] Yamamoto. My first things I wore were this Toronto label named Blitz, and they were designed by a woman named Marilyn Kiewiet, who worked at Amelia Earhart—do you know Amelia Earhart? Sandy Stagg was designing there, and then she became the costume for Rough Trade in the '70s, and dressed Carole Pope and Kevan Staples. I loved Rough Trade when I was a kid—I saw them when I was 10 and it made quite an impact on me. It was way more than my classmates were paying for clothes at the mall, but it didn't faze my parents that much. So I wore, basically, what Carole Pope wore for the first few years of my life.

The radiant mask that Margiela did seems like such a ripoff of you now.

Oh, that's very kind of you, but that guy was a genius. My only connection with fashion really, other than interviewing people, when Marco Zanini was rebooting the House of Schiaparelli, he read The Show That Smells and sent me a beautiful note, he let me know that he was thinking of that book for his first Schiaparelli relaunch. He's no longer with them, but I was really thrilled that couture week, that that was in his brain. I don't know what Martin Margiela would think of this book.

He's basically withdrawn now, isn't he?

He is. As far as I know, he's an antique dealer with his boyfriend.

Well, he was always quite reclusive, and I think people thought it was a publicity stunt ...

It's not.

No.

That guy's as good as his word, you know? He left and he left 100 percent. I don't know anyone that knows him, but I know people who know people who are good friends with him, and he's not in fashion, he doesn't care about fashion, it's done. I hope that Martin Margiela would be amused by my book. I thought he was such an explosive designer in the early days ... who knows. Maybe I'll get sued. They'll come take what little I have, which is, like, a box of Eggos in my freezer. They can have them.

I wanted to ask what it's like working at Type.

It's good. It's humbling, in that now I have a book coming out, and part of my brain is like, Are people going to like it, are people going to write about it? And it's good to go to a bookstore where every day you unpack 80 new novels that all deserve some attention, and it's very hard to sell books, not a ton of people buy books, it's a mystery why some books take off. I try not to get too anxious about it. The other half of working at a bookstore is that I'm just baffled by the things I hear and read. There are no grants, awards, fellowships, literary festivals, residencies in my life. I've never experienced these things.

I'm old, and I work these events for writers who are having experiences in terms of touring and press that are so foreign to me. It's a little hard on the ego sometimes to stand and open books for people to sign, or to get them their coffee, but I have such a fondness for self-immolation and humiliation that I think it suits me really well. That I have to submit myself to promoting other people all the time, and helping them and serving them. I think there's part of me that likes that.

When people write about your work they often call it "spare" or "minimalist," I guess like Lydia Davis or something, and I love Lydia Davis, but that makes no sense to me. Your prose is concise, but it's way too gaudy and theatrical for me to think of it as minimalist. I was wondering, does that come naturally to you, or do you have to work it into that shape?

Um, so, my first response is "thank you," because I never think of myself as a minimalist. Like, there's no way a big rhinestone brooch can be minimalist. Two, I feel like it can't be minimalist because no matter how short my piece is, it's packed full of shit that no one wanted to know about. So I feel like everything I write is exceedingly long [laughs], because it's giving information to the world that the world doesn't want. Thirdly, it comes naturally. I went through a little period when I started writing where I wrote longer pieces, and my friend Ken Sparling taught me to cut out the crap, but in fact the crap was not flowery in any way, it was the same sentences over and over, it's just that I was reducing the impact by having six of them instead of one.

My rule is, I don't write a line unless I can amuse myself or it seems new to me. So there are lots of instances I would like to describe—I mean, now I have trouble getting people out of one location, in the last couple of books. I would like to walk down the streets of Washington, but I couldn't think of a way to write about Washington that was better than the ways I had read other people write it, that didn't make me laugh. That makes my books very short, because I don't have all that many ideas, but I try only to use the ideas I like [laughs].

You also use repetition a lot, but in this almost musical way, syllables chiming together.

You would have to persuade me there was a musical influence on my books, but I love Tin Pan Alley, and I like musicals. And I feel possibly that repetition is Broadway-ish, the star singing it and the chorus repeating it, the orchestra reprising it. Also, as I said, I'm a really obsessive writer, so if someone says "faggot," the next person has to say it twice, and the next person can't say it less than twice. Things just start to snowball, because I can't stand the way they look on the page if they don't follow a certain visual pattern. So part of it is musical and part of it is ... whatever that is that drives me to do that.

Do you know Ronald Firbank? He once wrote something like: "I think nothing of filing fifty pages down to make one crisp paragraph, or even a row of dots."

Revising is ... the most pleasing thing, I think. Cutting stuff out. At least the phase where I have to get something on the page, I find so exasperating and aggravating. But revising? What a pleasure. I can think, I'm so tired, I'm going to bed, and I'll flip [the manuscript] open and think, I'm going to revise a line, and it's so fabulous. It's a combination of obsessiveness, sexual pleasure at cutting stuff ... and also I'm always amazed when I read writers, how they can have a good sentence and then a paragraph setting up another good sentence, but the setup is just blah, you're bringing nothing to it that anyone else couldn't bring. I just can't believe that it gets in books. It does, though—that's what books are composed of, connective stuff that people don't care about to get to the scenes that they do care about. So I guess I get that from Ken [Sparling], if it doesn't give me a laugh, cut it.

I think you mentioned somewhere being a big fan of James McCourt, who is so obviously a Firbank acolyte. I recently read Mawrdew Czogowchwz, and a lot of that book is organized by list-making, lists of things like outfits.

I love McCourt. I was going to say he's a maximal writer, but I'm not going to peg him that way, because it's just amazing how many sparkling sentences he can come up with. I can't do that, I don't have the imagination or the wit, but in the same way I think Severo Sarduy is like that, that book Cobra, it's just one stunner after another. It's just incredible. And not in the service of plot, or character, but in the service of pleasure and bitchiness and sharing great gossip. There are writers who write really long books that I think are dazzling, but I think mostly it's just serviceable. I would love to write a book as long as James McCourt, but in my mind my book sort of is that long. I don't register length, which the industry is obsessed with. "We can't show this around because it's not this word count," or it's not thick enough ... I just don't want my prose to waste your time.

You said you're writing this Count Chocula book, which reminds me of something my friend merritt tweeted a while ago, that all cereal mascots are bratty bottoms, except for Cap'n Crunch [both laugh].

Let me think in my book. Yes, that's true.

Is it just Count Chocula, or is there also Tony the Tiger, or...

It's Count Chocolog, Boo Brownie ... oh my God, they're all stupid chocolate puns and I can't even remember the Frankenstein one now. Frankenfudge. Because of copyright. I guess my Count Chocula is mostly just eating ass the whole time, but that can be top or bottom, right?

It's like a liminal zone.

Yeah, I don't know if you can tell that. Anyway. I think he's probably a bottom. And Cap'n Crunch ... I wouldn't think of him as a top, anyway. I think it's all bottoms without exception.

Cap'n Crunch to me is kind of the daddy-dom type.

Oh, it's so overcompensating. With his ship and everything? There's no way. I think it's more like the island of Doctor Moreau, I think a parrot is fucking him or something ... The real star of my Count Chocula book, really it's this poet Stéphane Marshmallarmé, and then Arthur Rainbow. So they're in it, but they're sort of a backdrop to the decadent and symbolist poets. Cereal poets. That book is done, I just haven't shown it to anyone. I want that to be a trilogy—I want to write about Disneyland. That might be the third book. The second might be about The Andy Griffith Show. I want to write a television thing—as I get older, I realize that period of being a kid and watching television is ancient history. So I feel more comfortable writing about it.

I shouldn't even think in trilogies, because I don't advertise that, and I don't tell my publishers that, but in my mind it is. In my mind now there's pre-cancer and post-cancer books. The Count Chocula one was mostly done before I got sick, and then I feel like this one is going to be more like The Well-Dressed Wound, because for better or for worse, I liked how blank that was and how angry it was. Although I don't want to manufacture anger. But it seems like the world's not letting me do that, it's giving me other things to worry about.