What it means to be modern is to be creatures of oil.

—Stephanie LeMenager

What if oil could speak? Is it already saying something to us?

— Jaspreet Singh

i

I wanted to write an oil story, different from the narratives I’d encountered, and a scene from Homer’s Odyssey kept gurgling through the murk of me. To find his way home, the lost seafarer Odysseus must travel to the underworld to receive a prophecy from the blind seer, Tiresias. In the land of the dead, he encounters the diminished, gloomy shades of heroes and traitors, “tender girls” and “men grown old in pain.” He meets Tiresias, receives his prophecy and then he catches sight of his mother among the shades, learning in that moment of her death. She makes no gesture, no sign of recognition. Rising to approach his mother, Odysseus tries, three times, to embrace her, and “three times . . . she went sifting through my hands / impalpable as shadows are, and wavering like a dream.” The beautiful pain of this tragic confrontation has long lurked in me, but why did I feel there was a connection to oil?

ii

We live in the oil age, a unique moment in history, but the story of oil has yet to be told in its full complexity. Parts of this story are untellable, and other parts won’t be fully understood until long after the oil age has breathed its final, ragged exhale.

We’ve become acclimatized to life at the speed of oil. Soaring through the sky in an airlocked vessel of carbon steel has been normalized; a day’s journey is a one-hour commute; “running to the store” means driving a kilometre and back. We take an ambulance to the hospital, intubate our faces in plastic receptacles. We devour fruits grown with nitrogen fertilizers, trucked across continents in the endless quiet cremation of the internal combustion era. We caress petroleum-derived mousepads, gaze on silicone body parts in the quietude of our most secret secretions. Oil coats our temporalities, protects and destroys our health, balms our intimacies. Oil is the single most definitive material of modernity—in a million big and small ways, it moulds how we live, how we want, and how we think; oil makes us who we are. For the last century-plus, oil has been ubiquitous, our dominant form of energy production. But where is the oil?

Reading Kate Beaton’s wonderful graphic novel Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, I was struck by the absence of oil. Frame upon frame of beautiful beaches paired against the chewed and diminished lunar landscape of the Athabasca oil sands. But where was the actual substance? Where was the bitumen, the petroleum, the tar? There is scarcely a drop of oil on the book’s pages.

In spite of the omnipresence of oil as energy, one of the most striking features of petroleum in the contemporary industrial world is its invisibility, its stealth. Oil is an open secret, the shadow side of our petroleum-hungry moment. In an interview for Postmodern Culture, energy humanities scholar Brent Ryan Bellamy notes the “absent presence of petrol itself,” a deft articulation of petroleum’s character. We love using oil, but we don’t want to touch it, see it, or smell it. Petroleum becomes a parable for the broader state of industrial alienation, a metonym for the many small horrors we prefer to keep safe in the buried unseen.

In The Road to Wigan Pier, his 1937 non-fiction account of coal mining towns in the industrial north of England, George Orwell explores oil’s sister substance, her fossil kin. Orwell had seen enough of landscapes and cultures marred by fossil fuels to characterize coal and its transformed geographies as infernal: “At night, when you cannot see the hideous shapes of the houses and the blackness of everything, a town like Sheffield assumes a kind of sinister magnificence.” Orwell spends pages describing “serrated flames” and sulphuric smoke and “dark satanic mill[s].” Also interested in the human cost of industry, he ruminates on the impoverished labourers of England’s fossil fuel economy: “It is no use saying that people like the Brookers are just disgusting and trying to put them out of mind [….] You cannot disregard them if you accept the civilization that produced them. For this is part of what industrialism has done for us [ . . .] this is where it all led—to labyrinthine slums and sark back kitchens and sickly aging people creeping around them like black beetles. It is a kind of duty to see and smell such places now and again, especially smell them, lest you should forget that they exist.”

Orwell’s strategy is twofold: he starkly examines the ugliness of industrial landscapes, and he does so in characteristically lucid, genteel prose. He makes the grotesque industrial scenery into a tableau that is, if not beautiful, at least sublime, an aesthetic strategy that is often rightly questioned in conversations around ecological art. Prefiguring the work of Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, one of humanity’s most influential chroniclers of petroleum to date, Orwell turns industrial ugliness into beauty through the elegance of his sentences. His goal, though, is to call attention to the brutalized landscape, to resist the impulse to “disguise” the “belching chimney[s]” and “monstrous clay chasms.” It is, for Orwell, a “kind of duty” to witness the scars and traces of coal production. Tempting as it might be to turn one’s gaze away from fossil fuels and the mess they leave behind, to do so is anodyne self-deception. The oil age demands confrontation.

iii

In December of 1861, Scientific American wrote that “there is nothing in the industrial world at the present time more remarkable than the production of petroleum.” From our present vantage, it can be hard for us to imagine this excitement genuinely, to read it on its own terms. Optimism about this new substance and its technological potential was both little-understood and wildly exciting for scientists and developers in this period. We see it, for example, in the petro-colonialist shading of J.T. Henry’s 1873 work, The Early and Later History of Petroleum: “The ‘thick scum’ which the Indians gathered, and which careful, prudent men, now guard against conflagration, flows into peaceable tanks, and, instead of lighting up the wilderness for uncouth savages, sends joy and comfort into thousands of distant homes.” What progress-oriented optimists like Henry saw in oil was, in part, the possibility of the relative democratization and widespread dissemination of wealth and resources. They did not see the toxicity, or the ecological tragedy, or at least they didn’t focus on it. They saw the miracle of billions of people travelling free and cheap, of farms and other industries producing food and necessities at rates heretofore unimaginable.

In 1992, near the beginning of his career, acclaimed novelist and ecological thinker Amitav Ghosh wrote in a review of Abdul Rahman Munif’s novel Cities of Salt that, “the history of oil is a matter of embarrassment verging on the unspeakable.” The gap of 131 years between Scientific American’s claim and Ghosh’s assessment opens a rift between enthusiasm and shame that graphs the curve of the petroleum age.

For me, it’s the embarrassment that lingers. Ever since George Wilson approached Daisy Buchanan with those coveralls on, that dirty rag in his hand, literature of the oil age has made petroleum into a mimesis of guilt and shame. Oil is a dirty secret, a nocturnal emission of our rocket-fueled world. But is shame helping us? What might it mean to examine this embarrassment, perhaps even try to think through it to a different view of oil? What might happen if we conceive oil beyond the pejorative, without judgement, attend it with a different kind of openness, even intimacy? What if we thanked it for its labour, blessed it back into the ground?

iv

I became obsessed with oil at some point in 2016. A few strands were braided in my fascination: my spouse and I were having a baby in the middle of a rapidly intensifying ecological crisis; I was following the unsettling coverage of the devastating Fort McMurray wildfire, which seemed an uncanny apparition of the “revenge of nature” narrative; I had attended an environmental humanities conference and was reading books like After Oil and Petrocultures; I was teaching literary theory in the Imperial Oil Lecture Hall at Western University; I had gone to the Banff Centre, seen the photos of the oily bigwig funders on the walls.

I should clarify: It wasn’t just oil that interested me. My particular fascination was the Lambton County oil boom of the late 19th century—Canada’s original, largely forgotten petrohistory. While living for six years in London, Ontario, I found out there was a town 100 kilometres down the 402 called Petrolia in neighbouring Lambton County. The name struck me, but I didn’t think much about it until I made some good friends from nearby Sarnia, a city that includes the area nicknamed “Chemical Valley,” where sixty-two petrochemical refineries crowd the banks of the St. Clair River in a tragically familiar contemporary monument to environmental racism and petro-colonialism.[1] In Chemical Valley, the air quality is the worst in Canada and the people that breathe it are mostly from the local Indigenous community of Aamjiwnaang,[2] whose lands have been gradually bullied away by oil companies. Accounting for the history of oil is particularly fraught and salient in so-called Canada, where petro-colonialism so often means theft of Indigenous lands and where Indigenous-led movements like Idle No More and Stop Alton Gas often lead our environmental resistance.

Why were the refineries there? The oil these plants were treating was mostly coming from the Athabasca mining sands in Alberta, but the history of oil in Canada begins long before Leduc No. 1 was discovered in 1947. It starts at the very inception of this nation, with the Lambton County oil boom of the late 19th century, now a buried footnote in Canadian history. The Lambton boom began in Enniskillen, Canada West, 500 kilometres to the north of Titusville, Pennsylvania, where Edwin L. Drake’s famously struck crude in 1859. A year before Drake’s find, in the summer of 1858, the entrepreneur James Miller Williams dug North America’s first commercial oil well and became known as “the world’s first oil man.” Williams’ discovery produced a lot of interest from roving speculators and soon the fledgling town of “Oil Springs” was born. Clay alleys ran thick with crude and teamsters hauled barrels north through the mucky “canal” of mud in the mosquito-thick bush. Men roved about with “dowsing rods” and self-styled experts called “sniffers” claimed they could smell where the oil lay in the rock. Drillers used mucking poles to vault between platforms because setting a boot in the muck was a risk. Gushers shot into the sky, thundering down on the fields and clogging nearby Black Creek, the sludge sitting a foot thick on the frozen river. Later, speculators blew the earth open with crude nitroglycerine torpedoes. Enormous oil fires burned for weeks at a time, prompting locals to term these ongoing blazes “oil weather.” Rainwater sold for a dollar a barrel and there was never enough to douse the flames. In January of 1862, Hugh Nixon Shaw, an Irish immigrant and “itinerant photographer,” drilled the region’s first gusher, thousands of barrels gushing wildly into the snow until neighbours managed to stuff the well with flax long enough to jam a pipe in. In the aftermath, Shaw purportedly quoted Job: “And the rock poured forth rivers of oil.”

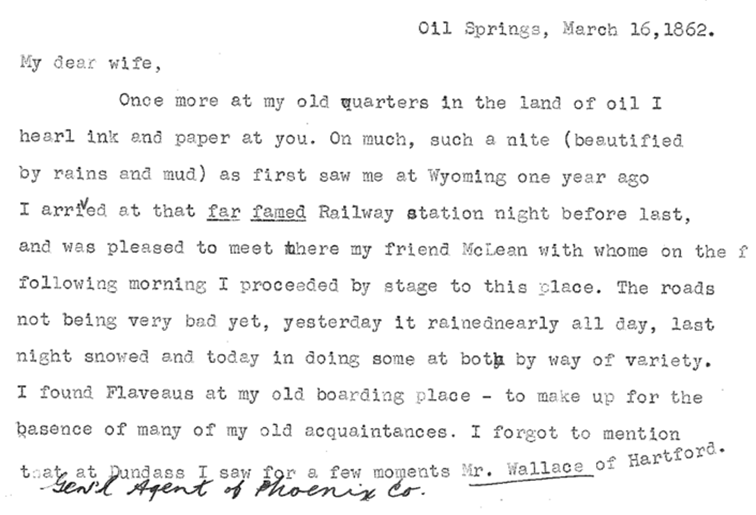

I was fascinated by the character of Shaw, but I was equally interested in a second personage: John Henry Fairbank, a businessman and (later) politician, and also something of a poet. Here is an excerpt from his letters to his wife, Edna:

Fairbank spoke, here, in a new language, of the peculiar funk of petroleum poesis (“once more at my old quarters in the land of oil I hearl ink and paper at you”). I was enthralled, my writers’ brain buzzing with hints of obsession and oil-lust, which I wanted to exaggerate and choreograph for the purposes of my narrative.

Throughout my journey into the underworld of Lambton County oil history and culture, I interviewed a lot of people, including engineers, refinery workers, local residents, activists, and Aamjiwnaang band members. One remarkable feature across the people I’d interviewed was reticence—they always seemed to be withholding.

One day in the early spring of 2017, Charlie Fairbank and his wife Patricia gave me a tour of Fairbank Oil Fields, a vintage “oil farm,” producing crude using nineteenth century “jerker line” technology and replete with farm animals and plastic replicas of drillers and wildcatters from the Ontario frontier oil days.

In the years that followed, I kept reflecting on the day I had visited the Fairbank family. The family had been kind but terse, subdued. I had gone inside, sat on Charlie’s faded floral couch, and asked him questions. His wife Patricia had lent me books. Through the living room window, I had watched a blue jay alight on a trembling aspen. But I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was making them uneasy. Maybe it was my fault, perhaps I wasn’t open or approachable enough. Perhaps they didn’t like my long hair. Perhaps they didn’t trust fiction. Maybe they just wanted to control the narrative. Quite possibly, it was all in my head. But I felt it. There was oil in the rocks beneath us, and I felt that too. In all of this I saw an eerie parallel with Bellamy’s notion of “present absence.” Oil is everywhere around us, but never glimpsed directly. It is changing the very structure of our atmosphere, but it hides serpentine in the rocks, rises up stealthy and convoluted in pipeline networks, rarely glimpsed by the consumer. As Don Gillmor has a petroleum businessman state early on in his 2016 oil novel Long Change, in the industry you never say “oil,” always “energy.” As material substance, petroleum is a silence, an absence, a ghost. As discourse, oil blooms in secret, a love we dare not name.

v

My grandfather, Victor Edwards, was an engineer who spent his working life as a lube specialist for Shell Oil. Vic passed his free time tinkering on his sailboat or tacking up the Strait of Georgia. (He died aboard that boat, having made it through those narrows, but that’s a story for another project). My grandfather’s career as a designer of refining systems brought his wife and children around North America, moving between Boston, Vancouver, Los Angeles, and Montreal before the family settled in Oakville, Ontario. My mother’s childhood was shaped by petroleum, mobilized and galvanized by the oil economy in ways she has never quite articulated because that’s not the way we talk about oil (we prefer it insidious, unseen, euphemized). If we look hard enough, almost all of us carry a story like this—a small, quiet, bruise of a story that tells the ubiquitous banality of our proximity to petroculture. This is one phase in the shimmering, oily chronicle that made me what I am: an oil person, denizen of the petroleum age. Inundated with petroleum-derived plastics, zoomed about by fossil fuels, fed on mutant crops fat with nitrogen fertilizers—my body is an autobiography of oil.

vi

To study oil you must become an amateur geologist, and one of the fundamental insights of geology is the revelation of the depth of matter and time. When you think hard about rock, deep time, and the earth’s core, you realize how shallow and impoverished it is to live on and think with the mere surface of this planet. As Robert Macfarlane notes in his powerful work of subterranean ecological thinking, Underland, “We know so little of the worlds beneath our feet.” Almost all human cultures have developed a complex and conflicted relation to what lies underfoot. Ancient Egyptian funerary practices, the Ifa Buruku, Enkidu’s “netherworld” in The Epic of Gilgamesh, and the underworlds of the Navajo, Apache, and Pueblo peoples. Macfarlane notes commonalities among cultural approaches to the underlands: “The same three tasks recur across cultures and epochs: to shelter what is precious, to yield what is valuable, and to dispose of what is harmful.”

In a 2023 essay for The Globe and Mail, Macfarlane describes his current project, on rivers, and concludes with a statement of the river’s animacy and agency: “This—a powerfully alive and enlivening presence—is the river I met a fortnight ago in eastern Quebec, and this is the river I hope will flow through the pages of the book I am writing. River as inspiration, yes, but also more than this—river as collaborator, river as co-author.” This is close to what I mean by “thinking with” the planet and its materials, including oil. I am thinking and writing not about the nonhuman world, or even alongside it. Instead, I reach my mind to be fundamentally co-implicated with the nonhuman, to offer it agency and animacy. Oil is with me in my thinking and, to the best of my ability, I hope to conjure and dream it in a way that allows the world beyond me its own styles of thinking. So that it might think in me as much as I think of it. This is the planetary and geologic with-ness I seek, what Heidegger called the mitsein, the “being-with.”

The term “katabasis” comes from the Ancient Greek and means a descent into the underworld, usually resulting in revelation. Again, such descents are common across many cultures: the Prophet Muhammad’s night quests in the Isra and Mi’raj; the Yoruba orisha Obatala; Dante Alighieri’s trip to the inferno; the Buddhist monk Phra Malai’s journey to Naraka to offer his teachings. Of course, descents into Hades are common in Ancient Greek stories, from the amorous Orpheus to the theft of Persephone to Homer’s wandering sailor, Odysseus. Macfarlane, again: “What these narratives all suggest is something paradoxical: that darkness might be a means of vision, and that descent may be a movement towards revelation rather than depravation.”

The story of oil must be a katabasis, a confrontation with dark forces to reveal new knowledge. So what have we learned from oil, and how are we telling its story? How can you write something so slippery, so intangible, so absolutely insidious? Do we write it at all? The critic Stephanie LeMenager suggests that “The world itself writes oil, you and I write it.” Perhaps it’s also oil that writes us?

I am certainly not a pro-oil writer, but I wouldn’t quite say I’m an anti-oil writer either—I’m more of an oil spectator, a bitumen flaneur. I want to look at oil honestly and openly, to examine the effects of our collective global “embarrassment.” Why are we ashamed of oil? Yes, it’s because of oil’s role in the current ecological spasm. But it seems to me it’s also more than that. When we confront oil, we face something powerful and profound in ourselves. Oil is a seepage we colour as dirty, filthy, ugly, unclean. But why should oil be beholden to such symbolization and cultural baggage? Oil itself is neutral and relatively inert; it’s the way we use it that’s the problem.

In seeking to find the appropriate approach for my own descent into the aesthetics of petroleum, it was quite natural to find myself in the territory of the eco-gothic. Oil is, after all, an underworld. A revenant. It moves, even now, (even depleted,) through the crooked caverns of rock beneath our feet. Oil is a dark reflection, a visible remnant of the repressed. Symbolically, oil is a Hades. It is also the psychological underplace, the mysterious murk of the subconscious. To contemplate oil is to think geology, vegetation, and deep time. If we want to think seriously about nonhuman life—how we encounter it, how we use it, how we love it—we must confront petroleum.

vii

Orwell wrote The Road to Wigan Pier in 1937, which almost perfectly bisects the techno-optimism of Scientific American in 1861 and Ghosh’s 1992 diagnosis of oil’s history as “embarrassment.” In 1937, Orwell was more than willing to sketch the coal country as an anti-pastoral hellscape—the industrial north is a “lunar landscape of slag-heaps” filled with “fiery serpents of iron,” “blue flames of sulphur,” and “evil brown grass”. But Orwell was also smart enough to know that this was not the only way: “When you contemplate such ugliness as this, there are two questions that strike you. First, is it inevitable? Secondly, does it matter?” Industrialism is not inevitable. I find this, like Orwell’s account in general both refreshing and depressing—depressing because all the damage that has been done never was necessary, and refreshing because of the reminder that we can choose other paths, turn away from our exhausted toxic mechanisms Of course, we have done so much harm since the time of Orwell’s writing, much of it irreversible. The end game of this great contamination is not a foregone conclusion—there is work to be done.

viii

Layers of dark on swirling dark, quivering dark in the deep dank brown black jeweled dark caramel dark, brilliant ravening dark bloated with light shimmering harrowing light-dark shivering risen glow from each vantage a new timbre clay-thick bitumen thin-drilled Devonian seep bones rock mnemonic Miocene revenants zooplankton revived corral tailpipe sunset workers hip-deep in muskeg quicksand sinkhole, drilled combustion crematoria sky tangerine rose rubber-footed children leap in parking lot puddles, marvel gasoline rainbows someday fossils, parking lot dandelions luff tender in the breeze.

ix

In an essay called “The Great Black North,” American non-fiction writer Andrew Blackwell recounts a visit to Fort McMurray on a “pollution tourism” expedition, and illuminates some of the central hypocrisies of Canada’s relationship to its role as a producer of oil: “Canada was both pioneering the era of dirty oil and leading the fight to stop it.” In his hilarious and unsettling account, Blackwell narrates a conversation with a local who says, “Fort McMurray is what’s powering all of Canada, and we don’t get that recognition.” While such a statement might make an eco-conscious reader want to scoff, the claim is more astute than it might first appear, offering a point of entry into the paradoxes of life in a petroleum state. If you drive a car, fly through the air, purchase petroleum-derived products like Ziplock bags, or use medical plastics, you are complicit in the oil economy. Even spending your days marching against pipeline expansion, crucial as that work is, also means living your live in the thrall of the oil age. All of us are oil people, and our legacy will be written in petroleum. Yet we so often don’t recognize the processes of oil production. The average consumer of oil and its chiliagon of products doesn’t habitually pay attention to tailing ponds and refineries because they are unpleasant.

If you look close enough, you might see that oil is more than what you think it is, that its stories run deep. You might see that oil is surprisingly beautiful—totally majestic and absolutely strange.

Oil is not only aesthetically beautiful when looked at close up. It is also buried life returning to the surface, long-forgotten bodies that have stewed in gaseous caverns in the rock for hundreds of millions of years. For me, therein is the fascination, the wonder of oil. Oil, usually thought of as dirty, sticky, grimy, and toxic, is ancient animal and vegetal life. This suggests an uncanniness, a strange world of subterranean admixtures, and an outright ghastliness: burning oil is in a very real sense burning ghosts of ecologies past.

I’m a climate writer who tries to think beyond doom and gloom, to open surprising avenues for rethinking the nonhuman and cultivating ecological joy, to let my work dance like clover in the cracks of parking lots. For some time I have been positioning my work within the genre of “dirty nature writing,” a term coined by scholars Caroline Schaumann and Heather I. Sullivan. Discussing this term in conversation with poet and eco-activist Tom Cull, I’ve said that dirty nature writing is a “composter” genre that is both a “sub-school” of and hostile to “conventional nature writing.” For me, dirty nature writing is a form of eco-oriented literary making that revels in messiness, stickiness, and entanglements. Dirty nature writing resists the urge to sanctify nature, instead acknowledging what Bill McKibben called the “end of nature,” confronting pollution and toxicity openly but without undue despair. But we can’t forget about the dirt in dirty nature writing. If “nature” is a pressurized terminological pipeline, “dirty” is a lexical hydra, frothing with pejorative connotations from race to class to sexuality. And there are paradoxes here: while the poor and racialized are slurred into dirt and filth, and while women are still expected to be chaste/pure/clean, the language of sexual desire reveals a prevalent fetish for “nasty” bedroom acts and talking dirty. As a writer attuned to the nonhuman, I endeavour to expose, illuminate, disentangle, and decolonize the often covert and problematic metaphorics written into ecological language.

Oil is the perfect subject for dirty nature writing; what could be dirtier and more natural than oil? Totally synthetic yet absolutely organic, ancient and eternal and filthy, it captures all the aporias I love to explore.

What I want to suggest is that, if we want to think seriously about the nonhuman, we need to unravel our profound entanglement with oil. And while it is easy to focus on the dark side of oil—to demonize it, focus on carbon crime and tailing pond filth—oil is also remarkable in its power, ingenuity, flexibility, and, yes, aesthetic beauty. To offer one example: most plastics are petroleum-derived, meaning oil gives us our TVs, our laptops, and many crucial healthcare technologies. Oil allows sick people to be transported to hospitals in helicopters and ambulances; many lives have been saved by oil.

We will be remembered as creatures of petroleum. But if we think about it at all, it’s in terms of gas prices and carbon footprints. Oil is a necessary evil, the filth we use but would prefer not to contemplate. Oil is afterthought—George Wilson wiping his hands on a rag under the eyes of TJ Eckleburg, Daisy speeding out of his life.

In their book Pollution is Colonialism, Dr. Max Liboiron suggests a new framework for thinking about plastics, drawing on nuanced and cautious senses of kinship and land (and the way these concepts are often appropriated by settler thought) to suggest that “plastics are Land.” Drawing on their own work in decolonial science practices through the feminist, anticolonial CLEAR laboratory, Liboiron’s sophisticated analysis of plastics insists that “purity relations based in discreetness and separation” are not appropriate for considering plastics. Plastics are with us, among us, entangled to the point where microbes seem to be evolving to consume plastics. As most plastics are petroleum-derived, the problem of plastics is of course the problem of oil. Rarely do we consider that thinking harder about oil—which is itself ancient vegetation—might reacclimatize us, might reorient our own understanding of our relation to nonhuman life. For me, insisting on witnessing oil, and developing a new, more compassionate view of it, is the most ambitious experiment in a practice of radical empathy for the nonhuman.

x

Returning to Book Eleven of Homer’s Odyssey, I saw it clearly: in order to invite the approach of the dead, Odysseus must sacrifice a black ewe, the best specimen of its flock. The creature’s spilled blood is a kind of enchantment: “I pledged these rites, then slashed the lamb and ewe, / letting their black blood stream into the wellpit.” The dead, in ghoulish frenzy, thirst for the ewe’s blood: “From every side they came and sought the pit / with rustling cries.” Black blood, pooled in a pit in the underworld, the shadowy dead approaching febrile and ravenous—it felt to me like my own prophecy, an augury of some oracle millennia dead, and I knew that my oil story was born in Hades.

And so we return to the pit, the shades huddling around the pool of blood in the gloom of the underworld. The metaphor is clear, of course. It was there in Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel Oil! and Paul Thomas Anderson’s adaptation, There Will Be Blood. Oil is the blood of the earth, a remnant and revenant of previous ages of massive biodiversity, burning hot in our age of perpetual tailpipe halitosis, a twisted inversion of the burnt offerings of the Greeks. We return to this new Hades, still asking what it means to be human, trying to learn how to embrace again this mother, this world always sifting through our arms.

[1] Here’s a recent report by the Yellowhead Institute on “data colonialism” in Chemical Valley: https://yellowheadinstitute.org/data-colonialism-in-canadas-chemical-valley/

[2] My research has been done in consultation with Aamjiwnaang historian David D. Plain and a sensitivity reading by Indigenous scholar Dr. Jennifer Komorowski.