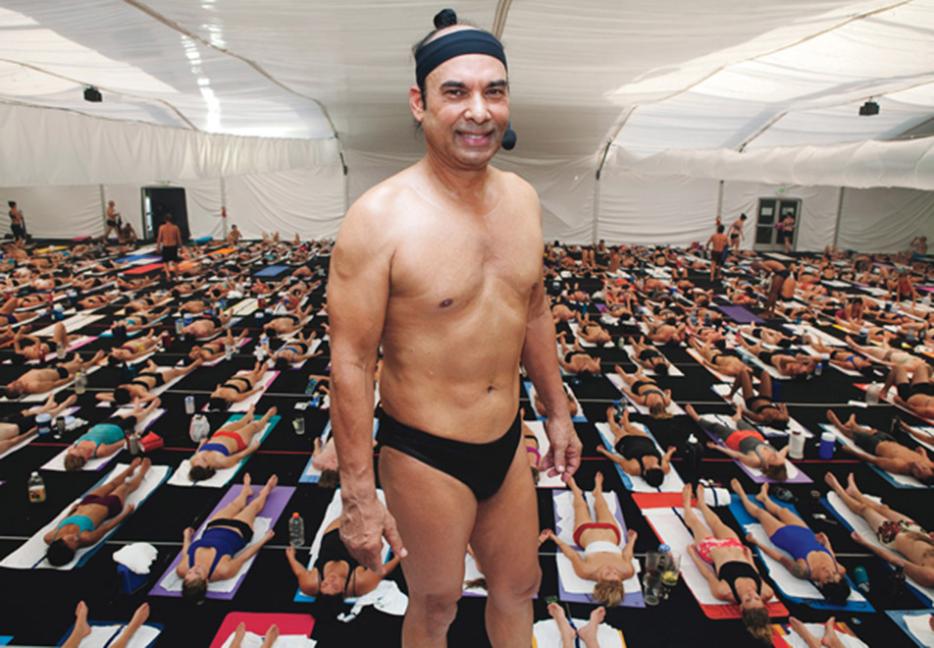

Bikram Yoga, arguably the largest yoga organization in the world, is famous for its grueling sequence of poses—26 postures that require students to backward bend into teardrop-shapes, or balance their entire bodies on just a few toes—performed in a sweltering room dialed in at 40.6 degrees Celsius. But in recent months its leader, Bikram Choudhury, has been in the news for reasons altogether unrelated to the yoga training he founded in the ‘70s.

Between March and June, four complainants filed civil law suits variously accusing the 67-year-old guru of sexual assault, harassment, and sex-based discrimination. On Friday a fifth suit was filed against Choudhury, by Larissa Anderson, alleging sexual battery. The Los Angeles Police Department has confirmed that Choudhury is being investigated for sexual assault or rape in four of the five civil cases, and that the district attorney is reviewing the witness statements.

The latest charges stem from an incident in 2011, in which Anderson, a former Bikram instructor and studio owner, says that Choudhury sexually assaulted her during a teacher training seminar—and according to her, it wasn’t the first time. Anderson further alleges that, after she refused to have sex with Choudhury, his company, Bikram’s Yoga College of India, withheld the name of her affiliate studio from its main website (studios teaching Bikram’s methods must be licensed, at considerable expense), causing significant financial harm.

In an exclusive interview with Hazlitt—the first time any of the five complainants have spoken with the media—Anderson talked about her more than decade-long involvement with the Bikram community, which she described as cult-like; her personal relationship with Choudhury; and a previous alleged rape by the guru in 2006. “I struggle with the career that I’ve chosen and the yoga I’m passionate about,” she says. “At the same time, [because of] the cult culture, the community, the hierarchy at Bikram, it’s been tainted.”

*

Within the Bikram community, Choudhury has long been dogged by accusations of misconduct, including alleged harassment, sexual assault, racial slurs, and rape. Now, with five civil suits filed against him and multiple LAPD criminal investigations underway, the allegations have spilled beyond Bikram’s devoted network and into the news.

The legal challenges began in March, when Sarah Baughn, a former Bikram Yoga instructor and high-profile member of Choudhury’s inner circle, filed a civil suit against Choudhury for sex-based discrimination and sexual harassment. (At the time, Baughn’s allegations were reported on by The Telegraph, The New York Times, and the Daily Mail, among others.) Two months later, women identified as Jane Does 1 and 2 came forward with their own suits alleging Choudhury had raped them. In June, a former member of his legal team, Minakshi Jafa-Bodden, filed a civil suit against him for sexual harassment, assault, and wrongful termination.

Jafa-Bodden’s suit, the fourth, could prove especially damaging to the guru; as Choudhury’s former head of legal affairs, many of the details in her statement appear to corroborate the other complainants’ accusations that he fostered an atmosphere of sex-based discrimination, harassment, racial bias, and intimidation. She claims that he also instructed her not to investigate incidents of alleged sexual assault. With the exception of Jafa-Bodden, all the complainants were at one time students or volunteers in Choudhury’s teacher training program. All the women filed their suits in California, home of Bikram’s Yoga College of India’s international headquarters.

Choudhury’s lawyer, Victor Sherman, tells Hazlitt that none of the claims—from Sarah Baughn, Jane Does 1 and 2, Minakshi Jafa-Bodden, and Larissa Anderson—will hold up in court. “If anything had happened, this would have been with the police years ago, and nothing came until 2013,” he says. “These people think, aha, they’re going to jump on the gravy train. It’s not going to happen. He’s not going to pay anybody anything. He hasn’t done anything wrong, and he’s going to be exonerated.”

Sherman said that Choudhury’s legal team will be filing a response to Jafa-Bodden’s claim this week, and that they will be going to court for Jane Does 1 and 2 later this month. “These are malicious claims that are not going to stand up in court.”

Choudhury is at the helm of an international business empire with more than 600 studios, including 62 in Canada and more than 350 in the U.S. With earnings from speaking engagements, teacher training seminars, and franchising fees, his company’s annual revenues have been estimated from anywhere between $3.6 million US to—by Choudhury’s own estimation to The Guardian—”Millions of dollars a day, $10 million a month—who knows how much?”

Yet the statements filed by Larissa Anderson, Baughn, Jafa-Boden, and Jane Does 1 and 2 are remarkably similar, and, if proved true, remarkably damning. Beyond reports of sexual harassment and assault, what emerges from the affidavits is a picture of a powerful man, wielding significant influence over subjects who fear as much as they love him.

*

Larissa Anderson was 22 when she began attending classes at a Bikram yoga studio in 1998, hoping to break from a pattern of alcohol and drug abuse she blames on a sexual assault she suffered as a teenager. She credits Choudhury’s teachings, based on traditional hatha yoga, with initially helping to turn her life around after a troubled adolescence.

Anderson had always been physically active, but she says that the yoga provided a workout unlike any she’d experienced before. “I got a lot of stress relief, mentally and emotionally,” she says. “I was also looking to change some aspects of my life, and follow a path that was healthier. I felt that [Bikram] yoga was the right path for that.” She also appreciated the sense of belonging it gave her to a community with strongly shared values.

“When he says offensive things, a lot of people say that’s jut how Bikram is. ‘Don’t let him steal your peace,’” Anderson says.

In 2000, Anderson says she met the man behind the poses she had come to know by heart. Through her then-boyfriend—also a co-owner of the studio she practiced at in Seattle—Anderson says she was invited on a trip to Whistler, British Columbia, where she would spend time with Choudhury, his wife and business partner Rajashree, and their two adult-age children.

“He was waited on like a celebrity,” Anderson says of her first encounter with Choudhury. “He stayed up late, so people would rotate around spending time with him.” Choudhury asked her to make him a sandwich. Her first impression was that others only spoke in Choudhury’s company when spoken to. “He was treated god-like.”

According to Anderson, Choudhury was both intimidating and enticing. He talked loudly and with bravado, unafraid to sharply criticize or compliment those around him. He often told students he would “kill” them, meaning he’d transform their lives with the yoga. Even his laugh—a gentle chuckle—could feel familiar and warm.

She says she was already in love with the yoga but her meeting with Choudhury in Whistler left her with a profound impression of the man. Once she met the guru, she says, she knew she had found her calling. Eventually, she asked her parents to finance her Bikram teacher training in lieu of a college education.

In 2003, Anderson says she travelled from her native Washington State to La Cienega, in California, then the location of Bikram’s headquarters. (It has since moved to Los Angeles.) It was there, she says, that she witnessed Choudhury’s unorthodox teaching methods and the inappropriate atmosphere in which they were disseminated. “Boss,” as his students refer to Choudhury at teacher training, would make racist statements, and homophobic remarks about how all gay men get AIDS; Bikram devotees interviewed in the course of Hazlitt’s reporting, say that he also made disparaging remarks about biracial people and veterans of the U.S. army. Still, Anderson says, there was a sense at teacher training that it’s best to keep your head down and make it until the end of the nine-week program. Graduating, after all, was at the discretion of Choudhury and Choudhury alone. The threat of expulsion was ever-present, and there were no refunds. 11Teacher training is mandatory for anyone who wants to be a Bikram teacher; studio owners who employ non-Bikram approved teachers run the risk of Choudhury finding out, and having their name removed from his online database of approved studios. Moreover, accredited teachers are sometimes asked to recertify every three years through a shorter seminar. The price tag for teacher training: anywhere from $11,000 to $13,000 for tuition, travel, and living costs.

“When he says offensive things, a lot of people say that’s jut how Bikram is. ‘Don’t let him steal your peace,’” Anderson says. “He talked a lot about religion, that he was more than Jesus Christ […] He would talk about gay people. He would talk about women. That they’re there to have sex with. That in order to keep a man, you have to keep your legs closed.”

Choudhury’s word is gospel. Anderson says that at his request, women brushed his hair and massaged his hands, legs, feet, and back, typically well into the early hours of the morning while he watched Bollywood movies. As multiple people have reported, this was a common scenario, something Choudhury asked of the women—rarely the men—who he wanted to be close to. Anderson says that he saw other women hoping to be picked by Choudhury. “Bikram said, ‘Oh I’m sore, my back hurts’ or ‘My hands hurt, I need somebody to brush my hair.’ Students—women—would be raising their hands, ‘Pick me, pick me.’”

Even with these intimate requests, Anderson says she didn’t have any truly negative interactions with the guru—she had already met him and his family, and was becoming a familiar face in Choudhury’s inner circle. Anderson successfully graduated at the end of the program, and went on to teach happily, at several studios in Washington, Colorado, and Chicago, where she also performed managerial duties.

In 2005, a year-and-a-half after Anderson’s graduation, Anderson’s then boyfriend—the studio owner who first introduced her to Choudhury—had a falling out with the guru. In the aftermath Choudhury demanded that Anderson pick a side in the dispute, calling her boyfriend a liar, manipulator, and “a bad person.” Anderson says she refused, and that for a time she felt shunned by the community that had once felt like family to her.

Choudhury’s lawyer, Victor Sherman, tells Hazlitt that none of the claims will hold up in court. “If anything had happened, this would have been with the police years ago, and nothing came until 2013. These people think, aha, they’re going to jump on the gravy train. It’s not going to happen.”

Anderson had designs on becoming a senior teacher, coaching in yoga competitions, even judging them. To do any of that, she needed Boss’s blessing. So, in 2006, Anderson called Choudhury to apologize and attempt to reconcile. According to Anderson, he said, “Okay, sweetheart.” He asked her to return to Los Angeles to spend some time with his family at their sprawling manor, reconnect, and take some yoga classes.

Anderson says that when she returned to headquarters, “it was like the last year and a half didn’t happen.” Everything was back to how it was before: staying at his home with his family, massaging his hands and feet as he requested, and taking advanced classes with former principal teacher and Choudhury’s right-hand-woman, Emmy Cleaves.

After dinner one evening in November 2006, Anderson says, Rajashree and the kids called it a night and went upstairs to bed. Choudhury allegedly asked Anderson to stay up with him on the main floor of the house to watch Indian movies. She says she agreed, but at around 1 a.m., exhausted from the day’s yoga training, said she wanted to go to bed. She says Choudhury asked her to stay a bit longer. He was seated on the couch; she sat on the floor in front of him, her back towards him.

Anderson alleges that Choudhury said something to her, she can’t remember what, but that when she turned to face him, Choudhury grabbed the back of her head and pulled her in for a kiss. She said no—”he did it again and I said no.” He tried a third time. “I pulled back and said I don’t want this kind of relationship with you,” Anderson says. “Then he got quiet and I thought, okay, that’s done.” But then he grabbed Anderson by the hand and took her into another room.

Anderson claims that she was so shocked by what was happening that she could hardly react. This was the home of her guru, a father figure who had enabled her to get beyond her difficult past: the sexual assault while a teenager, the drinking, the drugs. The alleged rape lasted for less than five minutes, was unprotected, and ended with Choudhury ejaculating inside of her. She says he then rose, pulled his underwear back up, and returned to the couch in the other room to watch the rest of the movie. “I was no longer in my body,” Larissa says. “I felt like I was watching it from above. I didn’t feel like I had a voice.”

She got up, adjusted her underwear and skirt, and went over to him to say she would be going to bed. “He said, ‘Okay, sweetheart.’” She climbed the stairs of his home and went into the bedroom she was staying in. “I did my best to fall asleep.”

[pagebreak]

*

As our subsequent stories will show, the apparent similarities between what Anderson says she experienced and the accounts of other complainants are striking the further you look into the legal documents. The women all allege they were drawn in by Choudhury’s charisma and magnetism—and the fact that he was the man behind a yoga they were passionate about—and they say they were torn by the prospect of leaving the community they were so deeply a part of.

Anderson says that even after her rape, she remained connected to the community, though to a lesser degree. She prepared to open her own Bikram studio in Kirkland, Washington, but no longer visited headquarters. Then in 2011, Choudhury offered her a job—her dream job: to work at Bikram headquarters. She says she couldn’t turn down the job she had been trying to get for almost 10 years. Besides, she was hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt from training to be a Bikram teacher and building her own studio, and she still believed strongly in his practice. She says she was doing what so many other people had done and told her to do: separating the man from the yoga.

Anderson agreed to come back to Los Angeles, and she says that shortly after Choudhury began to pursue an intimate relationship with her. “He wanted to get an apartment so we could be together,” she says, but she refused.

Then on October 31st, after a teacher training Halloween party, Anderson says she found herself alone with Choudhury in his hotel suite at around 1 a.m. while he was watching a Bollywood movie. According to the statement with her lawsuit, Choudhury asked Anderson to massage his feet, which she did. She alleges that Choudhury then asked her to massage higher on his leg, and asked if she wanted to touch him while gesturing at his penis, now visibly erect through his boxer shorts. Anderson claims she told him no. She alleges that Choudhury asked her, “Are you sure you don’t want to sleep with me tonight?” She was sure. When the movie ended, Anderson alleges that Choudhury tried to kiss her, but she said no again and got up to leave the room. According to Anderson, Bikram then forced her against a wall, pressed his penis against her, and attempted to kiss her more. He confined her to the room for 30 minutes.

At the time, Anderson says she had already received approval to start her affiliate studio, a process that is no easy feat: potential owners must pay a $10,000 non-refundable application fee, along with design and location plans, and then a slew of monthly fees that can total in the thousands. Anderson borrowed almost $250,000 from her parents’ home equity line of credit to pay for her studio. (The total cost was $211,619.)

Six months after the alleged assault, in May 2012, Anderson opened her studio. But despite its previous approval, and paying all the required fees, the studio never appeared on the list of accredited Bikram studios on the company’s website. Anderson claims this withholding negatively affected her business and she posted a loss of $58,617 in 2012.

Anderson talks about her allegations with conviction, never wavering on the details. Since the 2011 assault, she says, she’s been working with her doctor on symptoms of Posttraumatic stress disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. “I can’t even tell you how many times I’ve been unable to work or interact with people,” she says. “I have anxiety triggers, I have to lock myself in my apartment and I cry for days. I have a hard time getting close to people. It’s pretty much affected every area in my life.” But in spite of everything she says happened to her, she’s still profoundly in love with the Bikram practice. She believes in it. She wants it in her life. She continues to run her studio, under the more general designation of hot yoga, though it still operates at a loss.

Anderson’s allegations appear to be consistent with rumours that many community members had been hearing for years. People interviewed for this story allege that Choudhury has sexually assaulted them, harassed them, broken up relationships, and generally abused his power. “If there was a CEO in this country that acted like Bikram,” says Elizabeth Winfield, who went through teacher training in 2011, and is well connected in the community, “he’d be run out of the country.”

Many in the Bikram community say they are afraid to comment on the allegations. Several sources interviewed for this story were hesitant to speak on the record. Some even believed that we were calling on behalf of Choudhury’s lawyers in an effort to solicit information regarding the pending lawsuits. Others simply refuse to acknowledge the allegations; they question the credibility of the complainants because, as in the case of Anderson and Jane Does 1 and 2, they stayed or returned to the community after the initial assaults or harassment allegedly took place.

As Winfield says, “They’re going to say, why did these girls go back? Why did Sarah [Baughn] go back after he tried to sexually assault her?” But to explain this, she says: “They loved the person. Bikram can be very endearing. There’s this dark side and the light side.”

An earlier version of this story stated that teachers were obligated to recertify every three years. Recertification is not mandatory, but studio owners decide whether they want their teachers to recertify or not. The story has been updated to reflect this change.

--

This is the first article in a multi-part investigative series looking at the Bikram empire and the scandals surrounding its founder.

To contact the writer email [email protected]