Hallvard

15 May 2018

She’s been out of jail for three years and the no-contact order has been repealed for two, but this is the first time he’s gotten her to agree to meet him. Julian’s in front of Ham and Tony’s, which is still open but with a different owner, Mr. Rawley now living in Florida. The pavement’s warm, and the blacktop under his sneakers is absolutely hot, having baked in hours of sun. Karen has the same Honda, she said on the phone, and he’s waiting for that.

He can’t remember how they’d gotten there in her car that first time, but he remembers Karen showing him how to shape his lips for a kiss, the right kind of non-familial kiss, and watching him while he did it, looking at his mouth and then his eyes, waiting for him to lean in and start it. Julian had told the cops about that moment after an hour of questioning, when they threw in Chris Latham’s testimony about the kiss and fondling that he’d supposedly witnessed. Julian finally told them that Latham must have been lying, that they’d barely ever kissed in public after the first time. Then he told them the rest, a nice female officer who was only a little older than Ms. Rawley encouraging all the details forward, promising that Ms. Rawley wouldn’t have to know that it was him who gave them, unless there was a trial.

“If she’s as decent as you think she is, in the way you think she is, there won’t be a trial,” the cop said. And Karen did confess everything that night. Julian forgets the cop’s name, the way he’s been forgetting more about the past both distant and recent since he stopped going to school and writing and doing much of anything other than sitting on his parents’ couch and telling them that he’s almost made a decision.

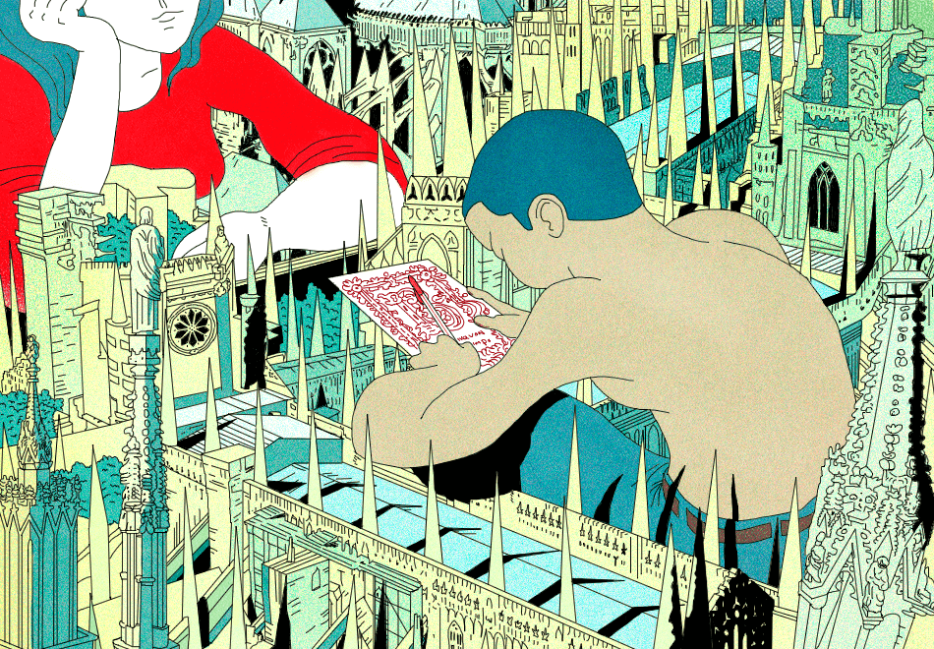

Karen had hidden the pages of the New Dictionary of Saints they’d made, printing them off and smashing the laptop before the cops made their first visit. Her last text had been to tell him so, that the pages were safe. The phone call the school had gotten was enough for her to make that move. The pages were hidden somewhere now, a relic, lost like those books had been in the Hemdale supply room, before Ms. Rawley resurrected them by passing a box cutter through the tape that held their imprisoning flaps down. If he could get the pages back and talk to Karen, just talk, he could figure out what to do next. Maybe tell the cops that he’d lied to them, that Karen Rawley had gone to jail to protect him, somehow, that she was the real innocent. That she’d been helping him.

The car, Julian thinks it’s the right one, turns into the parking lot and starts angling towards him. Maybe the pages are in the trunk. Julian starts to stand but waits, because she might want him to stay sitting at first.