I've interviewed Margaret Atwood twice before. On the eve of our third tussle, I notice a pattern emerging. I mention the upcoming interview to friends, colleagues, and they begin with the war stories. She doesn't suffer fools, they say. She's made people cry, after, when she's picked her teeth and moved on to the next, one intern told me. She throws your questions back at yooOOOOou, wails the chorus. They're not wrong.

My first interview was at the launch of MaddAddam, the final book in the trilogy that began with Oryx & Crake, and Margaret had me shook. "What could you possibly mean," she asked, “to suggest we're fascinated with the apocalypse? Which apocalypse? And to whom?" Just like that she began to puncture what I thought was a nuanced, well-researched set of questions. I was left sizzling, like too much cleaner in the drain.

The second interview, this time while on tour for her short story collection Stone Mattress, went better. She remembered me; called me a spring chicken. The spring chicken. (I add the definite article when I tell this in person.) I'd like to think we've settled into a routine: I sweat and sweat some more and she, rightfully, curves the assumptions behind my questions, but one never knows.

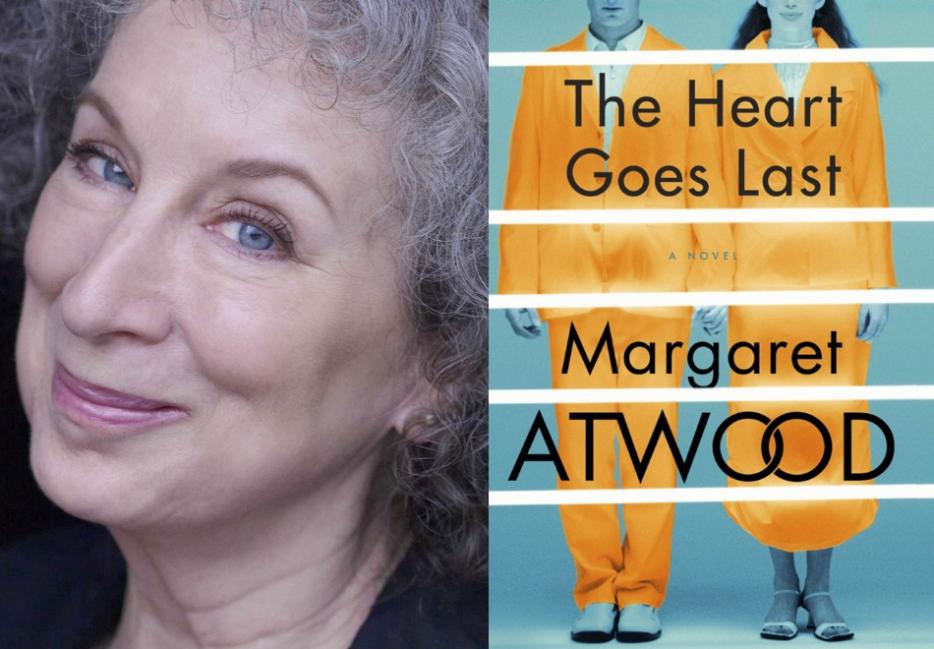

Anyway, round three. The Heart Goes Last is Margaret's latest novel. A return to the weird futures of her work before the Oryx & Crake trilogy.

The U.S. has collapsed, not unlike the country at the start of the Great Recession in 2008, though pockets are just fine, again, like 2008. Stan and Charmaine are one of many couples caught in the shrapnel of the apocalypse, living from moment to moment in their car. The threats to their bodies as real as the rape gangs closing in. They desperately sign-up for the gated community of Consilience, and its sister prison complex, Positron. But the people who joined with them aren’t there anymore. Where have they gone? And how does this tie into Positron’s meteoric quarterly earnings?

The pattern I mentioned earlier has one final step: I leave feeling like a better interviewer. When Margaret challenges your questions and rends her way through your silly attempts at resonance, it's because she's paying attention. She wants to know what you have to say, even when you don't. Margaret Atwood believes in you.

The interview was edited for time. Oh, and there are spoilers, too.

*

Anshuman Iddamsetty: I’m starting to lose my short-term memory.

Margaret Atwood: (Whispers) Maybe it’s age, dear.

Not this again...

(Laughs) What sorts of things are you not remembering? What people said two minutes ago…?

What I did over the weekend…

Oh. That’s bad. (Laughs) You had to have done something. Did you just sit on your computer the whole time obsessing over things?

I finished your book, thank you very much.

Well, you must remember what you did over the weekend, then. Or are you telling me you can’t remember anything that was in it?

No, everything else is a blur. Where I went, what I said.

(Feigns concern) Oh, no.

I don’t remember what chores I did...

Maybe you were wrapped up in the book.

Certainly not old age.

(Laughs) Says you.

Ok, ok. What was the seed for The Heart Goes Last?

The seed. I think the seed probably goes back, many years. One of the seeds was writing about the Kingston [Penitentiary] when I was writing Alias Grace. Looking at what people thought about prisons then and how proud they were of the Kingston Pen11The prison opened in 1901. because it as such an advance on what was out there already. It was supposed to be this model institution as contrasted with the manacles and straw that they had elsewhere. There was this utopian prison movement going on in the 19th century to make wonderful, improved prisons. One of them was something called the panopticon, whereby one person could stand at one point in the prison and see everybody in it. These motifs have been going on for a while, and of course if you read 19th century novels as I did you read a lot about prisons particularly through Charles Dickens. He was obsessed with them because of his father having been in one when he was a child. And then the efforts that were made to try and save the prison farm at the Kingston Pen several years ago, including the prize herd of heirloom cows. That was to no avail. More recently, just being aware. Of course I followed the whole Conrad Black thing as he made his way through the system and what he was allowed to have and not have. And being in Australia over the years, which started, of course, as a penal colony where they transported people and then set them to work. One interesting thing about that was first they sent only men who had done things like housebreaking and more violent types of things, and then they felt that if they sent some women out it would calm them down. They would settle down, have families, and make new people for the Australian colony. They did that but there weren't many female housebreakers littering up the landscape. So they had to lower the bar on the kind of crime they needed to commit in order to get transported, because they needed to fill up their quota. Whenever there’s quota, you need to start getting nervous. (Laughs)

So men started getting transported for housebreaking and women got transported for basically sneezing. When you have an institution that needs places filled up and that institution is a prison, what are you going to tweak to fill those places? And then it came to my attention that there were some for-profit prison schemes already in operation in the United States. Now, for-profit prison schemes have been around for a long time. We saw a lot of them in Nazi Germany, where they were using slave labour in factories. The problem with the for-profit prison scheme is that usually all the places have to be full before you’re turning a profit. And how are you going to turn that profit? Are you charging other places to warehouse their prisoners for them? Are you putting the prisoners to work? The first uniforms for the Northwest Mounted Police in this country were made by the female inmates of the Kingston Pen. They also made the first mail bags for the postal service. Well, hey, they’re just sitting around there, might as well get them doing something productive. (Laughs)

So, just thinking about prisons, thinking about when they started existing … they started existing when we started building buildings. When we were hunter-gatherers we didn't have prisons because, why would you? You didn't have a building. So there was no place to store people with other people being there to see they didn’t get out. Prisons didn’t start until there were buildings you could put people in. That didn’t start until agriculture. Until populations were sedentary in one place long enough to build the buildings and put the prisoners in. Some countries that have a low incarceration rate, have a low incarceration rate because they don’t bother with prisons. They just kill people. Statistics can be a bit deceptive. (Laughs)

But the whole thought of, What are we using them for? Don’t we really need to rethink this whole idea? It's gone through a lot of versions. Dungeons. Torture chambers of the Middle Ages and, more recently, punishment pure and simple. Then the idea of reformatories, you know, people should go in there and get reformed. In goes a nasty criminal, out comes a bright, shiny, productive member of society. Penitentiaries. You should go in there and be penitent. Everybody in the prison system in Canada in the 19th century was given a bible and taught to read so they could read their bible and be penitent. I’m not sure how that would work out in real life.

I mean, there’s an awful lot of violence in the bible.

Indeed. So what are we doing with this pretty expensive thing that we do? The criminal justice system. You asked me what the seed was, I’m looking at the absolutely for-profit prison scheme that is attractive to people because it solves a couple of problems. It comes into being in a time of economic downturn when a lot of people have ended up on the street, like the people in 2008 who found themselves unable to pay their mortgages and without a job, and they were living in their cars, or worse. So we start with Stan and Charmaine, to whom this had happened. They’re living in their car. They see this thing being advertised which is a gated community of Consilience, that has at its centre a prison, Positron. And it’s a time share. So you spend a month being a prisoner and then you change places with the people in the town. They get to be the prisoners and you get to live in the town. Think of the benefits that that offers: Number 1, a nice place to live instead of your car; number 2, time sharing. So that one house could basically take care of two families instead of just one. That’s the bright, shiny, outward face of this scheme. Which is supposed to be self-sustaining and profit-making, but what is the dark side we shortly discover? How are they making that profit?

Given the origins of our prison system, it almost feels like incarceration is baked into the history of our species.

Well, baked into part of the history of our species. There are sort of these grey areas between arresting people for criminal deeds, then that can segue over into slave labour. Did you see Gladiator?

Yeah.

So there’s an example. In the midst of a society that runs on slaves, one of things you don’t want to be is a slave. Kind of bottom of the heap. But one of the things that was never questioned was the need for slavery. Who’s going to do the work if you don’t have slaves, so.

You mentioned Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon. The utopia of prisons. Looking back, what he was trying to do seems utterly laughable.

It does to me! (Laughs) Maybe I shouldn’t have said the utopia of prisons. The new and improved modern model proposed by Bentham, who was a utilitarian always looking for new and improved ways to do things and he was the person who said, “the greatest possible happiness of the greatest possible number.” Notice he didn’t say, “the greatest happiness of the greatest number”–there’s a possible in there. So what is possible, we have to ask, under every situation?

What he proposed felt so contemptuous to the notion of what it means to be human. To suggest cramming more and more people in an optimized cage is the best answer to why crimes are committed in the first place.

You’re not talking about the rather lavish and agreeable Consilience and Positron prison model of the book. You’re talking about what we’re doing here in Canada now. And what we are doing in Canada now is cramming people in. We’ve also cut funding to the prison system so that the correctional officers–the guards and people working in that system–are expected to do a lot more work for a lot less money. And they are campaigning against the present government. Now, it's a very weird situation when correctional officers are coming out against somebody who says they’re building bigger and better prisons and they’re tough on crime. So what is it that they know that the rest of us have somehow not caught up with yet?

And yet, as you said, our current prime minister seems committed to being tough on crime.

But it’s not tough on crime, it’s actually soft on crime. It’s rotten on crime. Because you’re not solving crime, you’re just making more criminals. More and angrier criminals. You know, every kid caught with a joint goes in the slammer, you’re actually creating more criminals, and you’re certainly making life very pleasant for drug trafficking. Because if you take a substance like alcohol, for instance, during prohibition, that people are used to having, and to some extent used to escape their daily worries, and make it illegal, you’re just inviting the formation of the Al Capone mob. Which is what happened. And why people finally said, okay, we can’t be doing this anymore. So, watch who supports maintaining that this is an illegal substance, those are the people making money out of it. Follow the dollar.

The town of Consilience is this idyllic refuge from a world that’s gone to shit. But like other attempts at engineering society, it too resembles a prison.

Only if you want to get out. And do you want to get out? I catch mice in the summer. Being a kind-hearted person I don’t catch them in traps that make them go “squeak squeak,” I catch them in a swing top garbage pail with peanut butter on the lid. And then you have to transport them across water. So I put them in the canoe and paddle them across a body of water and then let them out. The problem is getting them out of the garbage pail! By that time, they want to stay in it. They’ve bonded! This is mine, I’ve peed all over it, I’ve got my nice mouse smell all over it. You have to turn it upside down and hit it in the bottom. It’s in Alias Grace as well, that people get accustomed to a situation they know how to run. Craig Davidson’s Cataract City begins with a guy coming out of prison and, I think, the first sentence is something like, “The only thing scarier than going into a prison is coming out of one.” That is scary. You’re disconnected from everyone you used to know. You’re there without a support group. Your nice plastic garbage can you’ve become accustomed to.

You’ve always had a deep-set skepticism for most social structures.

I have an inquiring mind.

And that’s healthy. How does one cultivate a similar distrust?

I wouldn’t even call it distrust. I would say peel back the immediate surface layer and let’s see what’s actually underneath, if it’s possible to find that out. As a child, of course, I grew up looking under dead logs to see if there might be a newt. Most of the time there wasn’t a newt. Sometimes there was. I should say salamander since newts are the ones in puddles

This was in Northern Quebec. Not literally the wilderness, but—

Yeah, it was literally the wilderness. Was it a town, was it a village–no, it was not. It was actually a house in the woods. At that time, quite remote. Now, of course, we have better roads.

How did that prepare you for the outside world?

I think it makes you improvisational. Because something breaks, you can’t just go to the store. But it's very handy to have a piece of wire, some safety pins, some pliers. (Laughs) So you learn to fix things. You learn to repurpose things.

That sounds like the perfect skillset for a writer. Or poet.

One of things poetry does with words. Words often have multiples uses–even in the same line in a poem. And why I went out of Philosophy into English was that in logic ‘A’ cannot be both itself and ‘Non-A,’ at the same time. Whereas with poetry you want it to be both ‘A’ and ‘Non-A’ at the same time.

I’d like to talk about the idea of infatuation in The Heart Goes Last. The lengths—

Oh, the infatuation of Stan and Charmaine for people who are not each other but are other people to whom they are not married.

There’s also the infatuation with the very idea of Consilience. A reprieve from chaos.

I wouldn’t even call that infatuation. Let me put it to you: if you were living in your car beset by criminal gangs every night who want that car and would hurl you out of it and bash your head in to get that car, and you were offered this nice other place with a real bed and sheets and towels and–we’re also stuck on bathrooms, aren’t we?–this sort of luxurious bathroom, wouldn’t you want to take it?

Absolutely, but–

That’s not infatuation. It’s a choice between one really horrible thing and another thing that you haven’t really closely looked into but that looks pretty good on the outside.

Well, that’s the thing. Don’t you start to romanticize an idea and overlook the horror–

But we all do that, dear. That’s how people sell package vacations. C’mon, you know that.

(Laughs) FAIR.

You’re life would be wooooonderful and there’s a picture of someone running across the beach, plunging into the waves… And they haven’t told you about the sandflies. But why would they?

I’d like to talk about Stan and Charmaine. Stan is a remarkably unremarkable person. He is callous, rude.

Only up to a point.

He gets dangerously close to committing an unspeakable act.

(Leans in) He gets dangerously close to committing a speakable act. (Laughs)

I know there’s no one overarching male perspective, but do you believe that most straight, cis men are incapable of interrogating their desires?

Oh, they’re not. You’re totally capable of it. I’ve read enough fiction by men to know this is true. Male writers writing fiction are constantly interrogating their desires. Even in comics! “You idiot, why did they do that?!” they say to themselves.

Usually after they did that.

Alas. Men will tell you a huge amount about themselves in the fiction they write. But, of course, nobody writes a novel from a totally wizened and good person. Number one, it wouldn’t be believable; number two, it would be freakishly boring. Come on. It would.

No, for sure. Stan’s a perfect vessel for the madness of the thirsty guy. He constructs this whole new life while lusting after this abstract ideal of a woman.

The other thing is, when you come right down to it, we all have bodies. And bodies are limiting. Things happen to them. They get older.

(Whispers) They get wrinkles.

What?

(Laughs) I don’t see a single wrinkle on you dear.

There’s no mention of wrinkles in the brochure.

No, it’s in the fine print. So, of course we’re always abstracting. We abstract and we leave things out of the picture. In the romantic fiction mode you may have noticed nobody goes to the bathroom. But people do in real life. It used to bother me a lot when I was a young reader. I would be reading along Sir Walter Scott those days, Ivanhoe, and there was poor Rebecca shut up on the dungeon and I thought number one, what is she eating, nobody is ever feeding her anything, and number two, where does she go to the bathroom?

No mention of a bucket?

No! Nothing. “What is going on here?” said my child mind, rather practically.

You’re just peeling back the layers.

It’s high on the list, for kids.

You’re no stranger to writing violence, gratuitous violence. And yet this novel is coded as unusual for the amount of sex in it.

It’s not too up close and specific. It’s mostly what’s in people’s heads. Sex is, kind of. Isn’t it really?

24/7

(Laughs) I DIDN’T SAY IT! YOU DID!

In your new novel, sex is portrayed as an act of violence.

Moderately. Not to the point of killing anybody.

Well, things are done without consent.

In this case it’s forced upon the man in the equation. Not physically, but psychologically.

I mean, in the spectrum of assault...

In the spectrum he’s engaging with things he wouldn't voluntarily of his own free will probably do.

There’s also the matter of one of Charmaine’s friends, who undergoes a procedure against her will. That’s unquestionably an assault.

Yes–your mind is rearranged so this is the only person you’ll ever love. Right, it’s very Brave New World.

What drew you to explore this particular future for sex?

Because it’s possible. Once these things are possible, what kind of uses are we going to make of them? In a free and democratic society with a lot of access to information, this, we would assume, would not be permitted. But in a closed situation, where you don’t have access to media, believe me, the temptation would be strong. To rearrange other people in that way, if you could. So somebody rejected your advances, all it takes is 20 minutes of anaesthesia, and they wake up all yours. Think of the temptation. Not only that, they like it. It’s not that you’re making them unhappy.

That’s what I found so monstrous? Especially when you suggest the public outcry. A muted, “Ehhhh, I mean, if she’s happy.”

Exactly. That’s what would happen. In olden day dramas–that’s why there’s a reference to A Midsummer Night’s Dream–this would be done with love potions. So what happens to Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, she gets some flower juice squeezed on her eyelids and wakes up, and she’s madly in love with this man who’s got a donkey’s head. Now, we can actually do that. If you look at old Roman charms, for instance. There’s this wonderful book called Ordinary Romans, and part of it was dedicated to what was on people’s minds, what were they worried about, what were they preoccupied with, and one of the things they were preoccupied with was loving someone who didn’t love them back. So there’s some samples of these charms they would get a sorcering type of person to do that says, basically, They should love me and only me, and if they don't love me all of these bad things would happen to them.

And they still want that. Of course they do.

I’m not opposed to exploring, consensually, duh, the brave future of sex. It’s intriguing that, and you’re very right about this, if we’re introduced to new technologies and new potentials, we’ll just retreat back to the same base desires. To grab someone off the street and make them ours.

As it were. What’s on the human list of fears and desires hasn’t changed a lot from the past 10,000 years. But how we are able to make those wishes come true and defend against those fears, those things have changed remarkably. So we’ve always wanted to fly, it’s why we gave the gods wings. Now we can. We don’t go flap, flap, flap, we get on an airplane. We always wanted to be the fly on the wall so we could see and hear what other people were doing without them knowing we were doing it. How fully have we built out that desire?

Quite fully.

We’ve pretty much wanted a multiple choice of sexual partners, but we’ve wanted those partners to be loyal to us alone. Do the math.

It’s pretty frightening.

All you have to do is go back and read literature and mythology for the past 4000 years or so, and those are our fears and desires. We’ve always wanted the ultimate weapon controlled by us alone. The magic table that would cover itself with delicious food.

The human story feels like something that’s been predetermined the second we crawled out of the primordial muck.

Oh, I wouldn’t be quite that determinist. We also have a sense of right and wrong, of fairness, that seems pretty built-in, too. We know some of the things we desire are probably not what we should do. That’s what makes drama interesting. If everything were predetermined, we wouldn’t even write literature …. What we put into our dramas and our novels and our fictions, we put characters who have the kinds of choices that we can either see ourselves having to make, challenges we can see ourselves having to face, these things are built-in to being human, as you say. It’s a little bit like the rat running the maze, I admit– this choice leads you to a dead end, this choice leads you to a piece of cheese, you don’t know which it’s going to be.

And at two very specific points in the book, Stan and Charmaine are offered that choice. The idea that there's a greater freedom outside their current predicament.

Yes.

And they both respond in the same way: “How do you mean?” I’ve been thinking about the construction of those four words. Would it be fair to say it’s a modern statement?

Right. A good question. In olden days we might’ve said, What do you mean? But nowadays we are saying, How do you mean? What they think they mean is the former, what they really mean is the latter. How does one go about having meaning in one’s life.

This goes back to promise of Consilience. There’s always going to be a scooter for you.

There’s always going to be a job for you. You know what to expect. You think you know what to expect.

Characters begin to internalize the rules and promises of Consilience/Positron. Bloodcurdling screams are ignored because they break the narrative.

Many have been the moments in history when people have ignored the bloodcurdling screams. We’re ignoring bloodcurdling screams all the time right now. Partly because there are so many going on around the world you cannot possibly take them all in. If you’re going to do something about bloodcurdling screams you’re going to have to pick a subset of them. Because you can’t handle them all.

It’s bad enough empathy can’t scale.

It’s difficult to be vitally concerned about more than 200 people, which was about the size of the primordial Pleistocene human group. So if you look at people’s Facebook and start analyzing which ones are actually friends (laughs).

I’m enthralled by Charmaine. How do you approach creating her? Or was she no different than your previous characters?

No different? No, not really. In a way it’s like meeting a new person. You think you know who they are, you talk to them for a while, and you find out something quite staggering, that you never expected would’ve happened to that person, and you’re quite floored by that and you can’t quite put it together with your initial impression of them.

Going back to how you repurpose everything, was there a particular, something, bubbling that led to Charmaine?

Everything’s bubbling all the time.

How do you shut out the noise, then?

Which ingredient in the cake makes it a cake? Well, actually, all of them. I’m thinking back to the time I was an early stage cook, about thirteen or so, and I left out the rising agent in my beautiful cake I was making and it turned out to be about one-inch thick! (Laughs)

So you can have all of the ingredients of cake, except one. And if you leave out that one it doesn’t turn into a cake. Have you ever done that?

I’ve done that a lot.

“You’ve done it a lot!” HA!

I’m not good when it comes to baking.

There’s usually a recipe.

Yes. I get it. I guess I try to approach it like a first year chemistry experiment. That’s where my mistakes come in.

Why would that be where your mistakes come in? If you got all the things and the procedure, that IS the chemistry experiment. It ought to work out.

I’m so rigid about it. What’s a smidge?

Oh, the smidge problem. Yeah, the old recipes say things like a piece of butter the size of a pigeon’s egg. Like, what?

...Moving on, there’s no shortage of examples of how literature portrays sex so comically. Why is sex so hard to write?

Well for anyone looking from the outside it is comic. (Laughs) Unless it's hot porn or something. Even that has its comic aspects. They have the Bad Sex Awards and they usually go to people who have tried to do it straight, tried to actually create steamy sex scenes and they usually are kind of funny. Maybe it’s my age, but I find all this stuff so funny. But not funny to the people experiencing them. At all. Not funny when it’s you, actually, in that scene that becomes sort of a life and death moment, but to anybody looking objectively at it. I suppose it's why we don’t like voyeurs. We don’t like to be judged from that perspective.

Do you think it’s a failure of the language?

No. I don’t think it is. Well, sometimes it is. I think it's quite difficult to write about in a heightened Baroque manner. It’s like all those altered state experiences. People writing about their drug trip. (Laughs) Ah, you’re too young, but when acid first came on the scene people were treating it like this Nirvanic experience. “Maaaan… I had the most out of this world experience… Aw, y’know… I dropped a couple of tabs… and I had this bonding with the tomato in my refrigerator, it was just wild…!” It’s like people telling you about their dreams. The dreams are very real and meaningful to them. But unless you’re pretty good at it, listening to someone else’s dream is, just, “Why are you telling me this?” It’s one of those experiences that are very meaningful for the people having it, and for people observing, which you always are when you’re the reader of a book, unless you’re hooked in so far that you’re inside the body of one of those people, it’s not going to be the same experience for the observer as it is for the person doing it.

One of the things that happens with sports, watching sports on television, is that people identify with the players. They put themselves in the bodies of the people doing it. And that’s why it sucks you in. You’re kind of there, don’t you think?

Of course. Would sportswriters be better equipped to write about sex?

Partly. But I think we should go back and do our homework and go back to the many novels that actually convinced us and we didn’t think they’re funny. There are such things.

Which authors do you think have done it right?

Well, you haven’t given any lead time on this! I have to go back and go to my library and do my research!

Ok,ok. Your novel begins with the best epigraphs, ever.

Now, there are three, to which one are you talking about? (Laughs)

All of them. I think they work best altogether.

Good. I do too.

Could you expla—

So you’re talking about the middle one called “I Had Sex With Furniture.”

Let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

(Laughs)

Could you explain the significance of the three you chose?

These are the epigraphs at the front of the book and they’re quotations. The first one is from Ovid who of course wrote a book called Metamorphoses in which all of the stories are about people being changed into other things, and this is about Pygmalion and Galatea. So Pygmalion made a statue of a beautiful woman and fell in love with it. He wanted it to be a real girl and started to go to bed with it and things. And finally, Aphrodite took pity on his plight and changed Galatea into a real girl, as they say, sort of like the Pinocchio story only with girls and sex.

The second one I stumbled across on the internet and it’s called “I Had Sex With Furniture.” And somebody actually designed a sofa that you can have sex with. It had sort of an appendage built into it, I guess, one of the arms. (Laughs) Why would you want to do that? I don’t know! I have no idea. It’s too weird. I predict this didn’t go very far in the market. But in the beginning of this post he says, “I did this so you don’t have to.”

(Cackling)

He then describes the experience of having sex with his furniture. And then the third one is from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and is talking about the fantasies that lover and madmen have. And as you recall that play is about people who get their love objects confused on purpose by supernatural beings Oberon and Puck, who are playing tricks on human beings. And that is indeed what it feels like: That fate has played us a trick by making us fall in love with this completely inappropriate person. I’m sure that’s never happened to you.

This interview is over.

(Laughs)