What was important to us in 2015? Hazlitt’s writers reflect on the quiet reverberations of the year’s big issues, and the loud ring of its smaller ones.

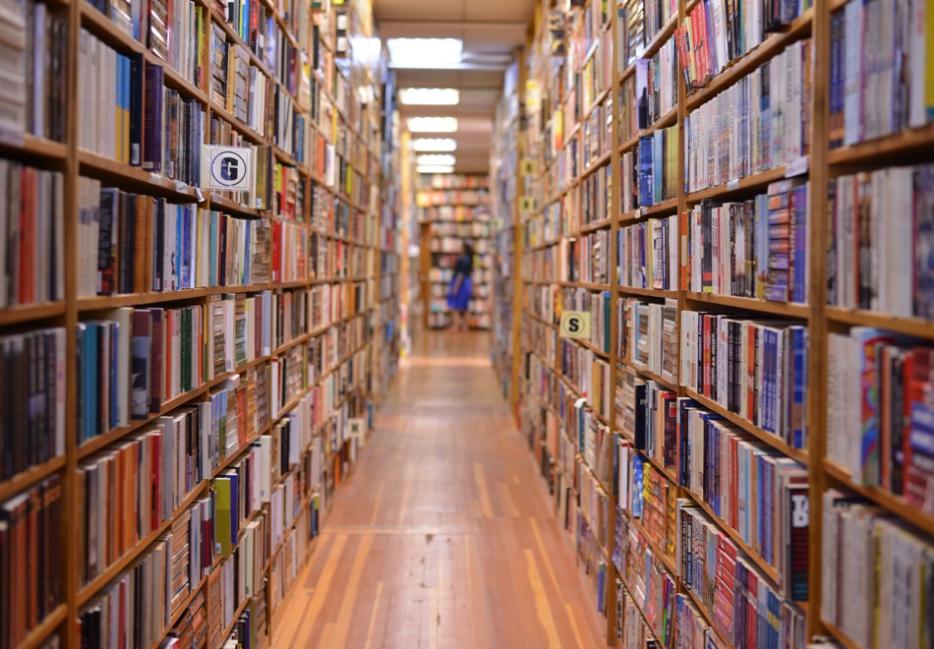

My shift at the local neighbourhood book conglomerate starts nightly at 10 or 11 pm. The regular daily employees have left; the customers have left. The escalator whirrs, Christmas music is piped in through the store speakers, the store smells like coffee and nutmeg, scented candles and pine potpourri: empty ambiance, waiting for tomorrow’s humans. We’re like those mannequins from Today’s Special, alive and moving only when everyone else has gone to sleep.

Skids full of stacked boxes fill the tiny storeroom in the store’s northwest corner. Our job, broadly speaking, is to empty the skids and move the product onto the floor. We use box cutters and scanners; we sort books onto one type of rolling cart, and non-books onto another type. We navigate each other’s spaces, dodging and bumping and twirling, speaking in a mix of English and French—finding common cultural ground and rolling our eyes at what people these days are willing to spend their money on. Later, we’ll shelve the candles, scarves and journals as well as the books: bargain, art, cooking, teen, self-help, business, science, history. Around midnight, when the mall turns the ventilation system off, the store will get hot and begin to smell like charred grease. Around 3 am, we’ll hit a wall and stop talking, put our headphones in. We’ll sit for a minute while reorganizing books at the bottom of a shelf, and have trouble hauling ourselves back up to standing.

I don’t hate my temporary, seasonal, minimum-wage job. I didn’t embed myself like some Canadian version of Mac McClelland, toiling away in service of a tell-all; when I clicked apply four months ago, my intention was to pay my rent. This type of job is nothing new to me. I’m thirty-one and I’ve been working since I was fourteen, usually at more than one job at a time. I’ve worked as bike mechanic. I’ve worked at Value Village. I’ve worked at Subway and Tim Hortons; I’ve worked at a vegetarian restaurant and a curry shop and an organic bakery housed at a Jesuit retreat centre. I’ve worked in communications; I’ve done print and web design; I’ve taught writing at universities. I currently work as a freelance journalist and a magazine editor.

When Jonathan Kay, editor-in-chief of the Walrus, published a short piece about class and journalism earlier this fall—arguing that class, not sex or race (as if the three things can be separated cleanly) was the “final frontier” of diversity in Canada, reception was mixed. Which is to say, some people lost their shit. (To the Walrus—and Kay’s—credit, they published a stellar rejoinder to his piece a few days later by Karen K. Ho.) I was one of the people who lost their shit: when Kay wrote that, to his knowledge, he’d never worked with a close colleague who’d experienced real hunger, or a serious health condition that went untreated for economic reasons, it struck a wound-tight, verge-of-tears chord. We may not be close, I thought, but I’m right here. I write for your magazine.

*

Here’s the thing: Neither of my parents went to university, no one expected that I would, and my family couldn’t offer me any post-secondary support. We could have been comfortably lower-middle class. We lived in a starter home at the edge of a small suburb of Hamilton, owned two cars, played hockey. There were a number of ways we could have been okay—I see them now, in hindsight, as an adult with agency—but we weren’t. My mother was an alcoholic, in control of the finances, and my dad was mostly unaware. As a teen, as my mom got worse, I hid the past-due bills for her. I knew our mortgage wasn’t getting paid, and we all knew when the hot water got shut off. After we bounced a cheque at the dentist when I was eight, I didn’t go back again until I was eighteen.

I started working young and often. Like a lot of people, I knew that a stable life full of what I wanted would require different things from me than it would require from a kid with a tuition fund.

We trade on prestige, and talking about how little we’re paid lessens that prestige, both institutionally and personally.

My first priority was to get out of my house. My second priority was to pursue the luxury of post-secondary education in the liberal arts. In other words, I class-jumped. I got to university, fish out of water, and gravitated towards other kids who were like me—came from working- or lower-middle-class backgrounds, talked funny, didn’t quite understand the mechanisms of polite academic society. Not all of us adapted, but I did: I learned what was appropriate diction; learned what the people who moved in academic circles liked to eat and drink and read and watch; learned what they wore, how they did their hair, what they did and didn’t talk about at the seminar or dinner table. I also learned that part of what was required of me after successfully accomplishing my class jump was to not talk about it. Before the term “good cultural fit” came into regular use, I understood intuitively that making the reality of my background invisible to people like Jonathan Kay was just one more compromise I’d need to make if I wanted to succeed.

*

Writing nonfiction and journalism brought about a similar kind of steep and sudden learning curve, and a similar kind of unspoken contract. It isn’t news that writing is a hard go, economically speaking. We love what we do and so we do it, but the work is often—especially for the first years of your career, when you’re building a portfolio and really learning your craft—not paid commensurate to your training, your skills, or your time.

About three years ago, I was working at Adbusters and went on a panel talking about consumption: do North Americans have too much stuff? For the first part of the conversation, I played the role I was supposed to play. (Yes! We do!) But near the end, I started thinking about the friends of mine, the working-class ones who’d gone to university and yet were still working in food service, having kids and raising them in the same small apartments they’d lived in as students. I broke my role to acknowledge that I was skeptical about the way we were framing the issue: this conversation is removed from the reality of a lot of people, I said. I think a lot of us are thinking less about having too many pairs of skis in our garages (we don’t have garages!) and more about how to pay the rent.

In nonfiction, telling the truth—particularly telling truths that are open secrets—is valued, and yet we’re cautious and cagey about money. We trade on prestige, and talking about how little we’re paid lessens that prestige, both institutionally and personally. In addition, showing roughness around the edges—talking in my townie lilt, dressing like I’d normally dress (black jeans; years-old sweatshirt; functional boots), being too honest about who I am or what my home life was like—threatens career consequences in what is already a very difficult and precarious industry. So I get it. I get why we lie, I understand why we obfuscate, I totally and completely support our decision to stand at the canapé table at that once-a-year fancy party pretending like we know what on earth we’re about to delicately coax off a toothpick while sticking to conversationally safe topics.

But that’s not what life is really like. The friendly neighbourhood book conglomerate, as well as paying me $10.55 an hour, provides a helpful analogy. At night, the division between the public and private spaces of the store is porous: we prop all the doors open and ghost through the doorjambs as if they’ll never again require key codes. Similarly, my work life is porous. I shelve books written by my friends; I visit the magazines I write and edit for, moving them to the front of the newsstands. I write this essay for Hazlitt, and, later tonight, I’ll probably unpack and shelve a box of books from Penguin Random House. I love the work I do for magazines, but it’s also true that I work elsewhere for minimum wage. I know that class is bound up with race and ethnicity and gender and sexuality, that I’m privileged in so many ways, that part of the reason that no one noticed I was here is because I was mostly able to blend in. I also know that my reality is remarkable only for its commonality—that many of you reading this will be nodding along, voicing whatever version of “yeah, dude” is common to your parlance.

We need to start speaking openly about these kinds of issues for two reasons: one, so that we can deepen our conversation about diversity, understanding that it’s not and will never be enough to add one person or two people or five people to our mastheads or panel discussions—rather, we have to change the structure of our organizations and our conversations so that they suit a much broader range of people (English can borrow one million words from other languages and still be English; to become French or German, its grammar must change, too). Two: so that we can come to terms with the impact of how we value writing, financially speaking. A lot of very talented writers and editors in Canada—some of whom we'd consider at the top of their game in terms of craft—make ends meet by working low-paid part-time jobs. (Because those jobs are flexible, because our career doesn't pay us enough to survive and yet we still want to give ourselves to it.) This is the reality that we live in, and it's a reality that people should be aware of. If it's not okay, then we need to re-approach our valuation of creative work.