What was important to us in 2016? Hazlitt’s writers reflect on the year’s issues, big and small.

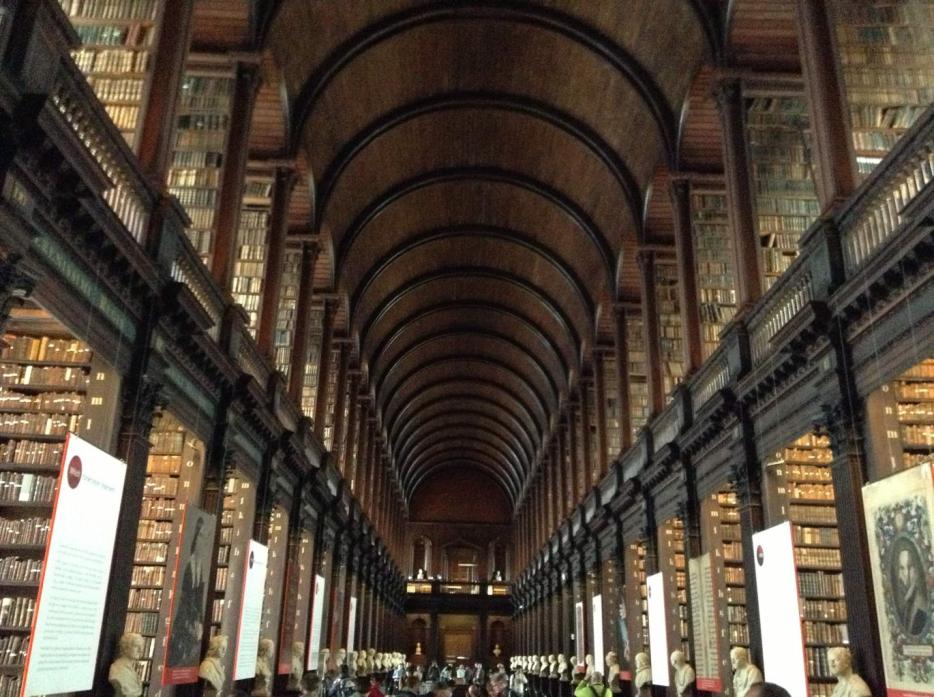

Just a few weeks ago, I participated in a debate about religion at Trinity College in Dublin. The motion was “This House Believes Religion Does More Harm Than Good.” During the debate, the fourth speaker, a white man who referred to himself as a wizard, declared Islam inherently egregious. The man, who wore purple velvet for the occasion, went on to explain why Muslim women needed to be saved. I was flabbergasted.

I was the second speaker on the opposition side, and I stood up to rebut, only to have him wave me away, his slinky hand curved downwards, lazy in retrospect, penetrating my identity with a dull argument about Islam’s historical tendency to be tyrannical. I sat down, incensed.

The whole charade was caught on camera. My eyes rolled far behind the back of my head—an immature act, yes, but the only agency I had over my body’s anger. Because, in that moment, my voice, a Muslim woman’s voice, was being drowned out by a man with a smarmy Noel Gallagher face.

Needless to say, the proposition team won.

I walked away from the debate fast, ghosting on the good-hearted festivities. Instead, I treated myself to an Italian meal five minutes away from the ancient Book of Kells, at a blue walled restaurant named Carluccio’s. Ordering a crisp and mineral glass of Pinot Gris and a side of beef rib off the bone, I sat and pondered the debate, realizing the result was a synecdoche of the larger world, and the politics I battle with daily as a Muslim queer woman of color.

*

White men love playing the devil’s advocate, cruising with the oversaturated use of, “Well, that’s your opinion” and negating the things you say because they can. White men can run for president with no formal experience, be accused of raping thirteen-year-olds, disregard grabbing pussies as “locker room talk,” and then become the leader of the free world.

I sat at Carluccio’s, looking around at the people beside me, feeling the after-effects of defeat. Part of the reason I couldn’t participate in the merriment post debate was that it was a reflection of my very real life. I couldn’t just pack it up and put it away into a small anecdote, or laugh at the antics as performative aggression, or even the formality of the event. It wasn’t a theoretical argument for me, it was about survival. To explain your humanity to a room full of people who already disbelieve in it is exhausting. I’ve been tired for years now.

Power is a performance, not a state of being.

Repeating the debate in my head, I lingered on the white man’s role in my feelings of powerlessness. The audacity of people to speak over my experience is the reality of my diurnal life. People think they know more about racism than I do, without ever experiencing it; Islam without ever talking to a Muslim in-depth, without examining Muslim life en masse. With these presumptions of knowledge, my power is taken from me. If a white man gave my opinion from their perspective—as an outsider—it would be lauded, it would be believed.

So, as I sat there at the shiny table of an Italian restaurant in the center of Dublin, my heart buzzed, my body pulsed, I suddenly felt awake. The rage from the debate had sublimated into something different, like a chemical, mercurial through my veins, I felt power. Power that had been taken away from me. Power that was never mine to begin with. Power that I’d earned, and power that I, finally, wanted to take as mine. I was tired of white men coming and going, taking what isn’t theirs and wearing it like armour. What was power if not, at first, an illusion?

Power is a performance, not a state of being. If you’ve never had someone anoint you with it, you’ll navigate your entire existence without tasting it.

But, now I wanted to taste it.

*

I wasn’t born powerful.

I was born to two immigrants and have been called everything from “gross black dirt” to the very imaginative “terrorist.” I’ve been hounded at airports, stopped and frisked, detained in a white room while my diary was read to me by two TSA agents at the San Francisco International Airport, turning each page with an entitlement that comes with power, luridly stopping at sentences, pausing with a menacing heartbeat, only to continue my silent echo of detainment. Somehow I survived it. I’m randomly security checked all the time, the SSSS on my boarding ticket a hallmark of a Muslim registry.

White people want to relate to your stories, so they tell you their traumas, too. We all have them, bruising the backs of our throats. But very often, it seems, white people want to hear the stories of our traumas only so they can tell their own. We’ve all been hurt. But some are given the option to lead, to live, and others aren’t even given the chance.

As a young brown girl who felt invisible, I didn’t know I was allowed to speak, until, until, until… now? No one ever told me, Fariha, speak, speak for yourself.

I bet no one ever told the wizard not to.

I have only begun to speak louder because I didn’t like the answers of those who speak for me. Yet their voices are still all too ubiquitous. This year has been the year of figuring out how to take the power that was never offered me. How do I take what is mine, and do it without guilt or shame?

*

Truth is, at a certain point, as each white man takes and takes and speaks over me with a huff, with a “That doesn’t sound right,” with a reference to The New York Review of Books, I’ve grown more and more enraged, and at a certain point it’s turned into the metal I’ve collected, alchemizing my silence and frustration into a very red and very tangible anger, spinning it into something that I take with me to war. I wield it against those who wish to silence me. I’m mad, I’m mad and that’s power.

Why you always mad? People have asked me through the years—saying I was too radical, too angry, playing the victim. That question is a way to dismiss the legacy of your pain. Why do you hate white people? They ask, a way to disengage with the constructs and context of racism, to diminish the role of whiteness in racism. It’s to gaslight you black and blue until you think you deserved the wounds that carve your body. It’s to force you to love those who have oppressed you, to remain (un)powerful, to feel (un)powerful.

But, in 2016 I chose power for myself.

I’m not sure why, but I rose at some point against the odds of my skin, and my sex, and my religion that everyone hates, I pushed through some barrier that felt like a psychic weight against my chest. I lifted myself from the agony of living a half made life, and the thinking that’s all I deserved in life, anyway.

Silence is something that I no longer decided upon. Silencing is an act of abuse, and though I’m not quite a believer in demonizing those who can’t speak (when someone is attacking you, sometimes your instinct is to shut down) I owe it to myself, and those like me, to call out racism and bigotry, so that I can pull it out at the roots. I’ve spent too many of my days acquiescing to white people, not wanting to cause any undue stress, when someone says something offensive, as if it’s my responsibility, and those marginalized, to keep the peace.

Now, more than ever, as Trump tramples on the ideologies that I hold dear, we need more people that will shout and scream and say what’s right. We need fearlessness now, against the tyrannical leisure of the neo-Nazis. We need power for people on the peripheries, for those who never believed in their own voice, who were too afraid to say anything under the ubiquity of miasmic bad opinion. Now it is time.

Nobody ever gave me power, but I’m taking it.

I’m powerful because I say that I am, I’m powerful because I know that I am. If power is an illusion, then I transformed into it. I chose power out of exhaustion, but I stay powerful because I’m still here.