What was important to us in 2016? Hazlitt’s writers reflect on the year’s issues, big and small.

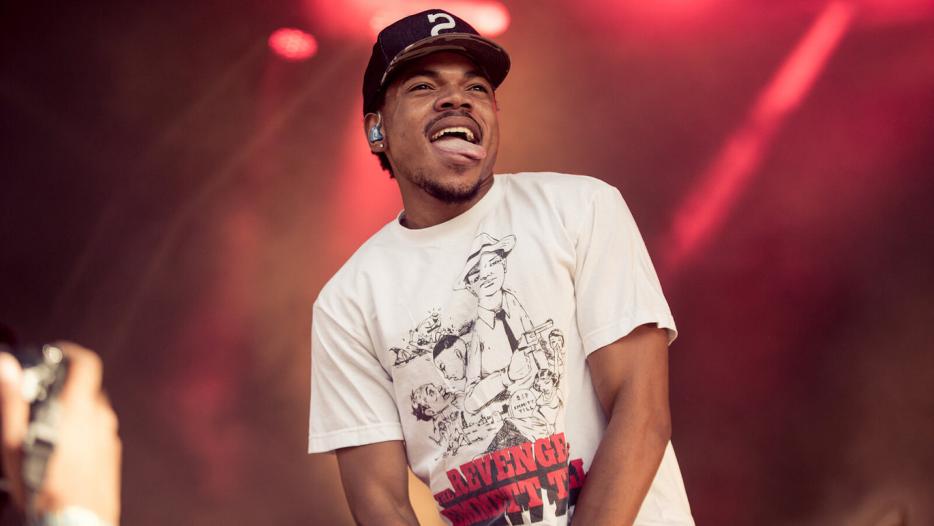

Chance the Rapper provided the turnup soundtrack for most of Black America in 2016, a vital reminder of just how much we need Black joy. On Coloring Book, his presence is enough to get an agnostic queer man like myself singing hymnals—he's that fluorescent pink sticky note on your mirror reminding you to “count your blessings well.” That highlighter-colored pink square you put up on a good day when you feel ready to take on the world.

His brightness could become too much, though, on the bad days, when depression seized so tightly you'd show up late to work despite having woken up with plenty of time. But through it all, Chance’s effervescence would cast away persistent personal rainclouds with an energy so magnetic that smiling felt almost mandatory. On “Finish Line / Drown,” he asks if we are ready for our blessings, pledging that “the people’s champ must be everything the people can’t be.”

What happens when we purposefully set aside time to meditate on the multifaceted nature of Black joy in the face of Black suffering? On Solange’s A Seat at the Table, she successfully provokes Black joy without shying away from pain, rage, or anger. As the Oakland-based artist Jay-Marie Hill writes, “the spectrum of Black emotion is necessary and divine.” A Seat at the Table’s tracks, interludes, and narration by Master P highlight the nuances of Blackness we are so often denied. The slow waves of “Weary,” a song Solange wrote on a particularly sapping day, capture the dichotomy of Blackness—“weary of the ways of the world” on the one hand, but never losing sight of the fact that locking eyes with another Black person on the street can smooth the edges on a particularly trying day on the other. We are tired, yet we belong.

We saw this year, as Vine—a major creative outlet for young Black folks—shut down, that the most affirming spaces for Black people tend to be those we create for ourselves. Many young Black YouTube creators considered new platforms; Akilah Hughes leveraged her audiences on Medium and Twitter to publicly call out how Black and non-Black people of color deal with constant plagiarism from corporations. Highly visible creators such as Franchesca Ramsey are catapulting their existing success to go beyond advertiser links and monetary gain, opting to mentor new creators to work toward social change. Since our arrival in the Americas we have created culture that is snatched without consent, yet we keep resisting.

We must never stop sharing Black joy, especially during trying times; we cannot survive any other way. Yet the value of Black joy is severely understated in the face of Black death and struggle. A sense of embarrassment surrounds the fleeting feeling of euphoria, forcing us to treat our joy as if it were a shameful act. But collective and individual Black joy must be a part of our daily routine if we intend to sustain ourselves well past the year 2017. Musicians, actors, and photographers have pushed us toward a new Black Renaissance. Guided by our elders, Black folks are learning from past mistakes and taking on the task of chronicling our own art and legacy in real time, all the time.

Black joy is not a luxury. Black joy is a necessity. Black joy is Black liberation.

*

Producing Black joy does not demand money, but economic insecurity affects one’s daily disposition in a way that someone like Beyoncé has likely not experienced in decades. This year, bell hooks critiqued the artist’s complicity in capitalism, and although Beyoncé’s artistic work feels untouchable, her declaration that she “just might be a Black Bill Gates in the making” represents the large chasm between fantastic visions of carefree Blackness and the financial reality for many Black people. In solitary attempts to build wealth and open new opportunities for those that follow, well-off Black people such as Beyoncé are made into unattainable trophies to which Black Americans aspire. White establishments refer to Beyoncé as an example of what—not who—we could become. Yet we face tangible socioeconomic barriers in attaining such power that inevitably cloud the possibility of Black joy.

Beyoncé’s net worth protects her from the economic hardships Black Americans face, but she is not safe from a particular form of anti-Black racism known as misogynoir. The reactions to Beyoncé’s Super Bowl performance, in which dancers took inspiration from the Black Panther Party, demonstrate that no amount of wealth can insulate any Black person from widespread vitriol.

Black joy is fantastic in the moment, but often the backlash swoops in so quickly that we wish we could take it back.

Black joy always seems to evoke a negative reaction, particularly around money. Part of the danger of Black joy, it seems, is the fear that success and vitality invalidates the very real struggle we face. Much of the treatment of Colin Kaepernick is rooted in his role as a professional football player; the general public expected him to sit down, shut up, and play in spite of the negative energy thrown his way. Kaepernick has been booed at work and been told to “go play in Cuba.” But his kneeling for the national anthem has become infamous on both sides of the political spectrum, leading to a surge in support from the Black community and charged complaints of un-American behavior from the more conservative white community.

Even Chance the Rapper, nearly unscathed in 2016 after the wild success of his Apple Music-backed Coloring Book, was not immune to the divisions and fractures of the moment. Tensions arose after Chance called out Black filmmaker Spike Lee’s Chicago-set Chi-Raq for exploiting Chance’s city of origin, and the two went back and forth, with Lee ultimately calling into question Chance’s father for his former role as Deputy Chief of Staff of the infamous Mayor Rahm Emanuel. Chance made his own position on Emanuel’s failings clear, though, and has been touring since.

Black joy is fantastic in the moment, but the backlash often swoops in so quickly that we wish we could take it back. 2016 was the year that the Black women who got kicked off of a wine train in Napa, California, finally settled their racial discrimination lawsuit for $11 million, but justice is rarely on our side in such a monumental fashion. ab, a Black and Salvadoran educator and organizer based in the Bay Area, says, “The biggest example of this [resistance] is when Black folks are out having fun, laughing, ‘being loud.’ We are just being normal, which is joyous. Right off the bat Black folks get policed, told to be quiet in public places.” Black joy is only accepted when it is contained, otherwise it is seen as disruptive to others.

Kristen Pender, a Black doctoral student at North Carolina State, recounts a powerful die-in action in response to the killing of Keith Scott. She writes, “As I lay on the floor, fighting back tears, I overheard a white male on his phone say something like ‘I don't care, I'll step on all of them' and I thought to myself, ‘really?’ Truly, I felt enraged at his lack of empathy.” Candice Robinson, a Black doctoral student at the University of Pittsburgh, echoed that statement, noting that even Black folks stifle our own joy. “Whenever someone seems to be having too much fun," she writes, "people are quick to say ‘why they so happy?’ I'm guilty of this sometimes too. It's often jealousy because I want to be able to experience that joy again, it feels so few and far between.” Black joy can sometimes seem like a scarce resource to hoard, rather than a renewable resource to share. But as Terron Davis, a Black undergraduate student based in New York, says, Black joy is Black peace, and our “joy keeps the haters mad.”

*

What happens when we bop to Chance, slow it down to Solange, or get bodied to Beyoncé? When we allow our Black joy to not just combat the inevitable Black death, but to double in intensity and frequency over time? I believe that we can recognize the perversity of our material reality as Black people on this planet while also making space for Black joy as if we were leaving just enough room in our coffee. As Sesali B. writes, “Black joy is just as much a strategy for improving the lives of black community as any rally or election.”

In her song “F.U.B.U.,” Solange epitomizes Black joy with precise, coded language: "Get so much from us/Then forget us.” Black cultural products and labor are the global backbone, yet the people behind the “trends” are discarded and often uncompensated. Even in moments of Black success, there's an obligatory process of centering the feelings of non-Black people; as she sings in the next line, “Don't feel bad if you can't sing along/Just be glad you got the whole wide world.” The song ends with pure exhilaration: “This us/This shit is from us/Some shit you can't touch.” As Black joy, Black love, and Black affection are policed, we reshape our joy every day to protect it from those who wish to see us fall.