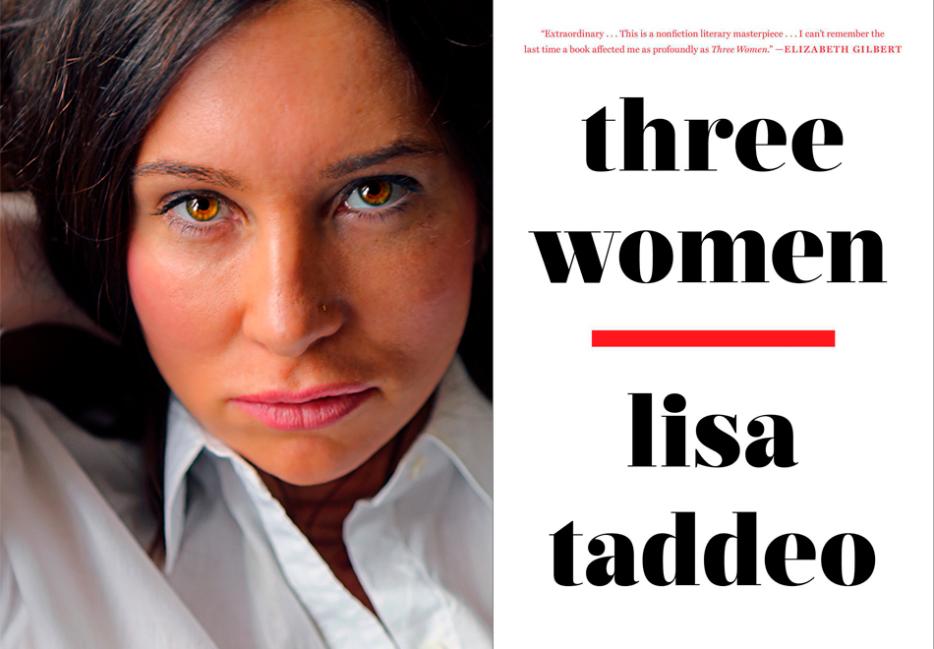

When Lisa Taddeo set out to write her new nonfiction book about desire, three women she met stood out. It took eight years for her to map out the inner workings of Maggie, a high school student in North Dakota who develops a relationship with her English teacher; Lina, a housewife in Indiana who works tirelessly to please a husband who refuses to kiss her; and Sloane, a poised restaurant owner in Rhode Island whose husband enjoys watching her have sex with other couples.

Throughout each account, we watch as the women unwind. As the coils holding them together give way, they experience a kind of renewal, face condemnation, and wrestle with their newfound freedom. And Taddeo is there not only to bear witness, but to observe and unpack the reactions of the women and communities surrounding Maggie, Lina, and Sloane. Three Women (Avid Reader Press) is not just a book about desire, but the consequences for acting on it.

Sara Black McCulloch: What led you to write about desire from this perspective? I read that what partly prompted this book was that you were reading Gay Talese’s Thy Neighbor’s Wife, and that you were put off by it—that it was written from a very particular and male perspective.

Lisa Taddeo: The main thing with Mr. Talese’s book was that, and you know I met him and he was an unofficial mentor for a certain part of the process, but you know, I found that there was just not a lot of emotion behind the acts he had been describing, and his book was different. It wasn’t that I didn’t like it—I enjoyed it very much. But at the same time, I just wanted to know more about... you know, there was a lot of swinging in it. And what I found with a lot of swingers is that they kind of go, “Oh you know, it’s fine.” And maybe for you it is fine and you don’t feel sad, but I just wanted to know about more of my own biases. I don’t judge them, I’m just so fascinated by it, but I couldn’t do it, so I wanted to know why these people could, in a sense, do it.

I just feel like there wasn’t much talk about why—the whys about everything—and that was where I wanted to have a departure. I think Talese was interested in different things, but I was also so fascinated by swingers that I went looking for swingers. I spoke to a lot of different groups of swingers and I could not find someone who gave me the sort of complexity I was looking for until I found Sloane and that was game-changing for me because she was the person I always looked for. I don’t think she’s necessarily representative of swingers, but what she is for me is representative of the complexity I wanted to know more about.

How did you find the women? I know, for instance, that you met Lina in a discussion group you were running.

I posted signs across the country, literally in bars and casinos. I posted them on windows of cars too, just everywhere: churches, bus stops, truck stops, everywhere. I went to the Four Seasons, seedy motels... I was just trying to find people.

I moved to Indiana because of the Kinsey Institute [which researches sex and gender] and because I met a doctor who was administering these hormone treatments to women and he was telling me about them. I found Lina really early. I think I spoke to her on the phone before I moved because the doctor had given me a number of his patients who were interested in talking to me. I didn’t know how fascinating she was going to be until she walked into that room and started telling her story.

I had read about Maggie when I was in North Dakota researching a different story. It was about women who were working as waitresses during the day at this coffee shop and by night, they were being trucked into the local oil fields to have sex with the men who worked there. So, I was reading about Maggie in a coffee shop and I read about the trial, which had just ended. I called her mother’s house and introduced myself, asked if I could come and tell them more about what I was doing, and then drove to North Dakota the next day.

I found Sloane by moving into her town to speak to several other people and at that point I was hearing rumours about not just a woman who was swinging, but a woman whose husband wanted to have sex with her every day and that not only did she allow it, she wanted to do it too. And that was the rumour. What was shocking to me about that, and indeed every woman and person that I spoke to, was the ways in which they were reviled by their communities for doing things like that. I just don’t think you should judge other people for their lives. So, I was interested in that.

That was how I found those three, but I spoke to hundreds of other people, at least 20-25 at length.

I also noticed a shift in voice and POV throughout the book, from diary entries to third-person accounts. What was the reasoning behind these particular choices?

They were all different choices, but I wanted the voices to be reflective of the women. For Maggie, one of the reasons why I started with the second-person was because she had been so reviled in the local press that I had in mind the most staunch disbeliever and I wanted that person to be able to instantly get inside her head in such a way that it would be impossible for them to not at least try to understand her. I wanted the literal experience. I did the trial and the other stuff more in the third-person to keep it factual.

With Lena, she found herself in the sexual moments—I would say more than anyone else did—and so I wanted her section to reflect that. I mean she told me everything so openly. It was just so infinitely interesting to me that I wanted to show how present she was in those moments.

With Sloane, who was the most reticent to talk and also the most eloquent but detached, I tried to tell her story in her rote voice.

You explored some really small communities that judged and condemned others for living their lives, and I wanted to know if you believe that there is such a thing as community anymore? You moved to these towns where these women lived—do you feel like a community is there to essentially police and surveil people now?

I do. You know, it’s funny, because my daughter is four years old and we live in a rather rural part of Connecticut, and a lot of people have said to me, "You should move here and here because there are a lot of moms and kids." But I moved to so many places and I’ve seen so many moms and dads, and no! There’s a lot more competition than there is community or a sense of community. You know how people say a child is raised by a community? I just don’t see that anymore in any way. Even with social media, it’s really become so much about who’s got what, and whose kid is doing this, and whose partner has a better career, and a nicer house—all of that! That’s what I found in almost every place. There were some places that were kinder than others, but for the most part, it was not a loving situation.

You don’t just discuss how women condemn each other but how they compete with each other, too. There was something really striking that your mom told you: “Never let them see you happy,” and by “them,” she meant other women. Were you noticing this in your discussion groups and even how these women were communicating with you?

One of the reasons I was most drawn to these women was because they were the victims of these things. They were less judgmental about the things that happened in their lives. They were victims of men, to an extent, but also the victims of other women. They were not so much the aggressors, and I found that really warm about them—that they didn’t want other women to necessarily suffer, whereas I found other women who wanted other women to suffer.

All the women that I observed for the final cut of the book were all, in some way, jealous or just condemning of Maggie, Sloane, and Lina. A lot of this is frankly biological, as men are not necessarily competing against each other, at least not the same way. The women are competing to be the thing that is chosen and that’s sociological and biological. The idea that men spread their seed—not be clinical—across a large group of women in order to perpetuate the species, whereas women are meant to stay back with the child and bear the whole situation. I find that really informs the way we move about. The sociological implications are that we also, at the same time, want equality. We’re very sentient, wise beings, but our biology and our sociology either mix or they don’t, depending on the day. I really think it’s other women because we’re fighting against each other for men or whatever—at least in heterosexual relationships. (It’s different things across different orientations and sexual predilections.)

The male gaze really fuels that too, but it many ways it also fuels the desires of these three women too.

We’re still rooted in it. We can’t change our history, but we are complicit in perpetuating it in the present. We’ve been living under it for centuries, and we can’t just wake up one day and change. We first have to admit that it’s there before we can figure out how to combat the negatives in our lives.

When you’re immersing yourself in someone else’s life, especially as a journalist, there is always talk of objectivity. Did you ever find yourself slipping, in a way, and judging these women, or would their stories force you to confront something within yourself? Or trigger the memory of a personal situation? Did you find yourself connecting with them on a deeper level?

It’s funny because there were countless things, but the thing that I think about the most is that when I was a kid, like 10 or 11, I was going to Puerto Rico with my parents. I had helicopter parents before the term was coined, and they wouldn’t let me out of their sight. And I just wanted to take a walk down the beach. They finally said yes and I was so happy.

That day, I packed baby oil because I wanted to get super-tan. I was wearing a black bikini with little neon butterflies and I loved it. I was so happy. I took Stephen King’s The Stand with me because I was a depressive kid. I laid down in the sand and fell asleep.

I woke up with two things: one was a second degree burn across my body that was insane. The other thing that woke me up, in fact, was a man, I don’t know if he was 30 or 40, but I knew that he was a man and I was a kid. He was licking my arm. The first thing I thought—I remember the feeling very well, and not just the tongue, but the feeling I felt in my head, which was, “I don’t want this man to think I don’t... like him?” I don’t know, it’s weird, but I still have that feeling today and I’m nearly 40 years old. It was shocking.

I went back to my parents and I did not tell them about the situation for two reasons: one, that I didn’t think they would ever let me out of their sight again, and two, that they would think I was a slut. And that’s what I thought. I was an 11-year-old girl. I didn’t do anything. I shouldn’t have put baby oil on my body, but other than that, I didn’t do anything.

It’s super interesting, and multiple things like that came up. And mainly, it’s about how the formative years shape the way that we are, and we desire, and in other ways that are more obvious in the present. And a lot of people weren’t aware of it. Neither was I!

We internalize those experiences and feelings of shame, and that plays out in very different ways: you have to be careful with how you’re perceived by other people. You need to be constantly vigilant. I noticed, too, that even the women you talked to couldn’t fully let go of this vigilance either. It’s a weird kind of invisible service in their public and personal lives. They’re always making sure that everyone else’s needs are being met.

And just the performative aspect too—just being aware of yourself and your attractiveness and I found that so much in everyone that I talked to—women and men. But men have this goal, which is an orgasm, no matter how sloppy and smelly they are. With women, some of them can, and I’m inspired by the women who can, but I myself have never personally found that. I will not do anything if my teeth aren’t brushed.

I wanted to talk about parents and what we inherit from them. In the introduction, you talk about your mother and the secrets she hid, and how that creates a barrier to communication—or not telling your parents what happened to you.

Yes, but also, it’s not that I didn’t think I could talk to my parents, it was more that I was ashamed. I thought it was my fault, too. I didn’t want them to stop letting me be alone. I didn’t know that I needed to go to them—I don’t think what they would have said would have been helpful.

With Maggie, we see that too—that she didn’t really confide in anyone because she couldn’t. The women you spoke to had these fractured relationships with their parents and people in their lives and they really had to compartmentalize aspects of their lives and themselves.

I think that a byproduct of growing up years ago—although this has less to do with Maggie, because with her, it’s more of a byproduct of where she’s from in the country—but with Lina and Sloane, they both had parents that they wouldn’t necessarily feel comfortable going to with the things they experienced. With that said, I think it’s the time, and that now there are a lot more studies about how to be with children. I don’t think people were really looking at that back then.

Are any of the women planning on reading the book?

Two of the women have read it. I’m in touch with all three of them pretty frequently, so they’re very much aware of the book’s publication date. I’m not supposed to reveal which two have read it. Some are a little more nervous than others about it.

Are you planning on keeping in touch with them and seeing how their lives turn out?

Yes! I am so interested. I’m close to them. I would call all of them friends, but the nature of our relationship is very much—it was mostly one-sided because I was asking the questions. With that said, there were many intimate moments that we shared about their men and about my own stories whenever I thought it was something they would want to hear or that would help them or make them feel comfortable because they were giving so much of themselves. It was organic.

One of the things that allowed women to explore their sexuality and desires was the advent of birth control, and in terms of what’s happening now in the U.S., this is going to have an impact on everything, but what impact will this have on desire?

I think that to make any heaving step forward, there’s going to be a thousand steps back. It’s always shifting and what’s going on now is awful, but I also hope that it won’t last very long and that eventually those people in power are going to die off and when then do, hopefully there will be less people taking their place that will deal with it the same way. It’s definitely going to change the way women talk about it, but I also think that it’s making voices louder because there’s a lot of rage.

Also men—in general and in the book—are threatened by their desire and tend to use it against these women in many ways.

Men get nervous when women have desires that go above and beyond their desires. I think that’s why there’s such a rise of this incel community coming out of the woodwork, because they’re hearing about what women want and they’re translating it into, “Women want to have sex with good-looking guys.” For centuries, men have wanted to have sex with good-looking women, but the fact that we’re hearing from women now is making a lot of men who are not confident—and this is sad and they should be heard—but the way that they’re trying to be heard is despicable and that’s a perfect example of what happens when men feel nervous about female desire.